IJDTSW Vol.2, Issue 2 No.5 pp.49 to 70, June 2014

Valmikis of Gujarat: An Existence in the Lap of Daily Exclusion

Abstract

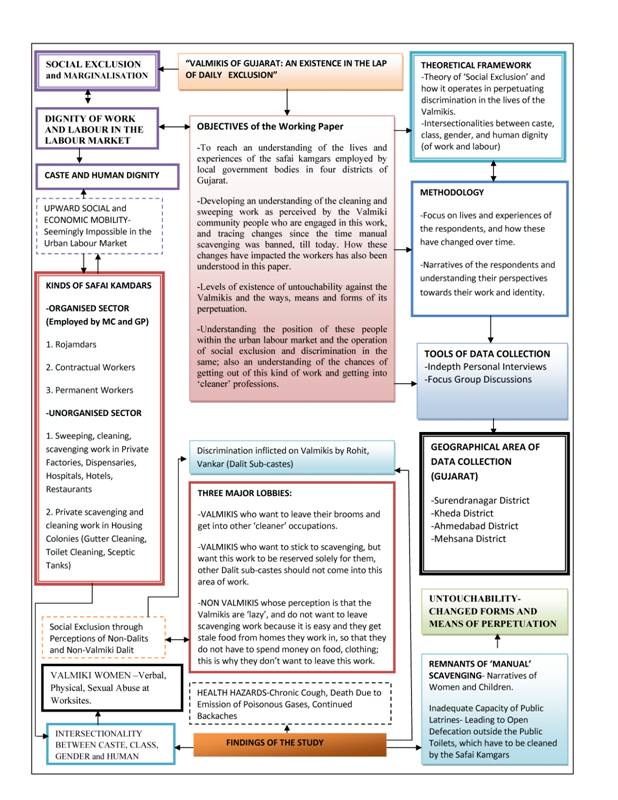

The current paper looks at the lives and experiences of the community that has been involved in the act of (manual) scavenging since centuries as part of the occupational structure that the caste system has attributed to them. The Valmikis of Gujarat still constitute the highest number of scavengers-sweepers in the Municipal Corporations and Gram Panchayats and due to unavailability of alternatives they remain bound to this degrading ‘occupation’ which completely dehumanises their labour and excludes them from the mainstream development discourse. The paper looks at the conditions of this particular community in four districts of Gujarat, and examines their labour within the framework of social exclusion, marginalisation and human dignity, and how the caste system acts an impediment for their social and economic mobility. It goes on to understand how the concept of untouchability operates in different ways in the lives of the Valmikis and how the intersections between class, caste and gender make the lives of the Valmiki women even more difficult. The paper is restricted to developing an understanding of what goes into the labour of this community and how and why they are still at the bottommost rung of the social order, even till today. The paper operates through various narratives of respondents from the Valmiki community whose lives and experiences form the most significant part of the same. The issues and problems of the scavengers in the organised sector as well as the unorganised sector are looked at through the lens of social exclusion, which forms the basic theoretical framework of the paper.

Introduction

The Preamble of the Constitution of India guarantees ‘Justice-social, economic and political; Liberty- of thought, expression, belief, faith, worship; Equality of status and of opportunity and Fraternity – leading to the dignity of the individual and integrity of the nation’. It seems pertinent to begin the current paper by stating the Preamble, because the issue that the paper deals with would develop an argument that would systematically debunk almost all of these constitutional guarantees, for a particular group of people, whose lives and experiences form the core of this paper.

The scavenger or the sweeper caste has been given various names in different parts of the country, the most popular amongst which are Bhangi, Valmiki, Mehtar, Lalbaig, Dhoria, Dharwani, Chuhra. In Gujarat, which is where the current study has been conducted, they are known as Valmiki, and they constitute a large proportion of the Scheduled Caste population of the state. Etymologically speaking, the different nomenclatures have different origins and it would be interesting to try and understand how and why these names came to be attached with the scavenger or sweeper caste. Mehtar is a word of Persian origin which means ‘Prince’ or leader. It is indeed surprising that the most oppressed section of the Hindu society would be given such a name which gives them some sort of respect and dignity. Some scholars have said that the application of such a name to the low-caste people is indeed ironical, but it is true that most lower castes have such honorific titles such as this which are used as methods of ordinary politeness or by those requiring some service from them and hence, just to get work done by them, this title has been attached to their caste. However, this explanation does not seem to make much sense, as we all know that the scavenging work was not something that the people of this caste had much choice about. More often than not they were forced into this kind of filthy work and the question of politeness and appeasing does not arise which renders the aforesaid argument weak in itself. Another, more plausible explanation has been given by Joseph Thaliath which he has essentially culled from the responses of one the participants of his study. He says that the origin of the word ‘Mehtar’ is most probably derived from their profession of sweeping the earth. The word ‘mahi’ in Sanskrit means ‘earth’ and ‘thirna’ in Hindi means ‘to be absolved’. Since they absolve the earth from dirt and refuse, the name ‘Mehtar’ has been given to the sweepers and scavengers. A third theory talks about another possible origin of the terminology, wherein ‘meh’ in Sanskrit means ‘urine’, and ‘ther’ in Persian means ‘saturated’. Their work with night soil seems to explain the origins of this particular nomenclature. The second name given to them, much more popularly used and used in a much derogatory manner, is Bhangi, which essentially means people who are addicted to Bhang, which is an intoxicating drug made from hemp leaves. Since, this nomenclature does not have anything to do with their profession; the only other explanation is their possible addiction to bhang. (ibid) Thaliath writes that Bhangi is the name for God and hence the children of God were called Bhangis; this however has not been talked about anywhere else and thus cannot be corroborated. They are also called ‘sarbahangi’ because they are ‘one with all and at the same time they are separated’. (Thaliat 1961) Another name attributed to the scavenger caste is that of ‘Valmiki’ which is essentially derived from the low-caste author of the Hindu epic Ramayana. This nomenclature is used widely by the people belonging to this caste for themselves as they see it as a dignified title for themselves, much better than the rest of the terminologies attributed to them by the so-called upper castes. The other nomenclatures attributed to the people belonging to this particular caste are Dhoria-because they were responsible for taking the dogs out on chains and Dharwani-because they stand in attendance at the doors of other people. As far the religion of the Valmikis are concerned, although they have always been considered to be outside the Hindu fold because of their untouchable, the irony is that they are deeply entrenched within the Hindu religion and practice all the rituals of the same, despite the fact that it is this religion which has led to their oppression over so many years.

The issue that has been dealt with in this paper is related to the basic identity of the so-called Scavenger/sweeper caste who are known as the Valmikis in Gujarat, which is where the current study has been conducted. There are various intersections that exist when one talks about the Valmiki community people because not only have they faced inhuman exploitation, oppression and marginalisation foe centuries, but the most disturbing fact remains that, not much has changed even today, despite the coming in of various acts and laws. It is true that on the face of it things seem to have become much better and the condition of the manual scavengers seems to have improved, but the current paper talks about how the changes have been largely superficial in nature, and the Valmikis who were earlier involved in the degrading ‘occupation’ of carrying night soil on their heads, are still involved in sweeping-cleaning-scavenging work in the Municipal Corporations and Gram Panchayats. It is important to provide a background about the so-called ‘occupation’ of manual scavenging and how it is deeply ingrained in one’s caste and also how it is next to impossible to get out of the webs of oppression unless and until one rejects the entire caste structure, which is intricately intertwined with the religious institutions of Hinduism.

Manual scavenging, the act of human removal of excreta from dry pit latrines, is detrimental to environmental, mental, and public health and is a gross violation of human rights. Manual scavenging is often the sole economic opportunity for Dalit (also known as Untouchable) women, who are often considered the most “dehumanized” members of Indian society. Mahatma Gandhi called it “the shame of the nation”, and yet manual scavenging continues to be a widespread practice throughout India. It is perpetuated and legitimated by the caste system. The Manual scavengers are a minority and are located at the bottom of the population that is considered to be outside the Varna system, known as Dalits who also comes under the constitutional category called Scheduled Castes, but within the SCs the scavenging community is the most neglected and deprived section. The names of the scavenging communities depicts that they are a ‘functional community’ recruited from a range of social and racial groups. It may be likely that one the reasons that led the people of the lowest strata to take up scavenging was an acute economic necessity; however this is only a proposition put forward by some scholars.

The identity of the manual scavengers is forever shrouded in mystery and a cloak of invisibility. This is because legally, this inhuman social practice was abolished long ago; the fact however remains that, there are still large numbers of people belonging to the Valmiki caste (located at the bottom of the caste hierarchy, even amongst the Dalits) who are engaged in this horrendous activity and this in fact is an economic activity and means of livelihood for many of these people.

Before we delve any further into this issue, it is important to talk about the laws and acts that are in place for the prohibition of manual scavenging and what steps the government has taken to ensure it’s complete abolition from society.

In 1993, the Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act prohibited the employment of manual scavengers by all local and national government authorities and also banned the construction of dry latrines, once and for all. However, following the enactment of this law, many states denied the existence of manual scavenging in their states at all, and thereby turned their faces away from ensuring that this law was implemented in letter and spirit by the State Governments. This completely defeated the purpose of the act and the violation of the same continued in the uninterrupted employment of manual scavengers by the local authorities as well as in the private sector.

Further, The National Commission for Safai Karamcharis was constituted on 12 th August, 1994 for a period of 3 years under the provision of the National Commission for Safai Karamcharis Act, 1993 to promote and safeguard the interests and rights of Safai Karamcharis. The National Commission had, inter alia, been empowered to investigate specific grievances as well as matters relating to implementation of programmes and scheme for welfare of Safai Karamcharis. The Commission is required to be consulted on all major policy matters affecting Safai Karamcharis.

The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Bill, 2012 states that “it would provide for the prohibition of employment as manual scavengers, rehabilitation of manual scavengers and their families and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto”. In the same breath it talks about how the Constitution of India assures the dignity of the individual; the right to live with dignity which is also implicit in the Fundamental Rights guaranteed in Part-3 of the Constitution; Article 46 of the Constitution provides that the State shall protect the weaker sections, particularly, the Scheduled Class and Scheduled Tribes from social injustices and all forms of exploitation. (Bill No. 96 of 2012) This Bill has recognised the fact that “the dehumanising practice of manual scavenging, arising from the continuing existence of insanitary latrines and a highly iniquitous caste system, still persists in various parts of the country and the existing laws have not proved adequate in eliminating the twin evils of insanitary latrines and manual scavenging”. The fact that a Bill was introduced in the Parliament regarding the issue of manual scavenging as recently as 2012 and also that it recognised the presence of this practice goes to show the extent to which this problem is ingrained in Indian society.

Although there has not been much organized pressure against the issue of manual scavenging in the form of unionization of the manual scavengers for their liberation etc, there has been much work done in the Non Government Sector to do away with this horrendous practice of carrying human excreta on the heads of people who are clearly treated as ‘lesser humans’ than the others. Some of the most important organizations like the Navsarjan Trust (Ahmedabad), Rashtriya Garima Abhiyan (Madhya Pradesh) have continuously been doing commendable work in this sector and due to their efforts this issue has been gaining visibility and thereby receiving whatever little government attention that it has.

Of course, the problem of manual scavenging clearly points to the lack of basic sanitation facilities for people in the cities as well as the villages, which leads to the construction of dry latrines that are required to be manually cleaned by people of just one particular community.

The history of sanitation facilities in our country has indeed been an interesting trajectory. Till the 1970’s, sanitation was not given any importance in the development of the country and only indicators which led to direct economic development held all the importance. However, during the 1980’s the planners started attaching some significance to the lack of sanitation facilities and it was decided that by the end of the Seventh Five Year Plan, at least 25 percent of the population would have access to basic sanitation; however, this was a big failure and not even 3 percent of the population gained access to the same as on March 31 st, 1992. (Patel 2006) Provision of sanitation was taken up as part of the rural and urban employment generation programmes like the National Rural Employment Programme (NREP), Rural Landless Employment Guarantee Programme (RLEGP). The biggest problem with these programmes was that they were implemented with a top-down approach, without conducting any proper needs assessment of the beneficiaries, with the result that the utilization of these facilities was less than 20 percent. (ibid) The lack of proper sanitation facilities led to the perpetuation of more and more dry latrines, which in turn led to the continued existence of degrading practice of manual scavenging.

The issue of the manual scavengers is thus an intersection of class, caste, gender, lack of human dignity, and social exclusion. And this is the broad framework within which the current paper would be attempting to understand the issue in four districts of Gujarat state; namely, Surendranagar, Ahmedabad, Kheda, and Mehsanna.

The situation is nothing less than gory, even today, after the passage of the 1993 and 2012 acts that prohibit manual scavenging of all forms. Many of the revelations are nothing less than shocking and they posit a big question mark on the whole ‘development story’ of Gujarat. The other questions that arise are, whose development are we talking about? Where do the Dalits, especially the Valmikis, figure in this development story? Talking about discrimination and exploitation, what comes to the fore through this study is the fact that much of the discrimination and exploitation that the people of the Valmiki community face are inflicted on them by the other Dalit sub-castes apart from the so-called upper caste people, who were always involved in inflicting oppression on the so-called lower-castes.

Dalits in Gujarat

Gujarat has a comparatively small population of SCs. According to the 2001 Census, the population of the SCs in Gujarat is 35.93 lakhs, which comes to 7.09% of the total population of the State of 5.07 Crores. The SCs in Gujarat are dispersed in all the districts of the State unlike the Scheduled Tribes the bulk of whom live in eight districts in the eastern part of the State. Out of the 18,275 villages in the State, as many as 12,808 villages have Scheduled Castes population. There are 2,361 villages and towns which have SC population of 250 and above. These villages and towns contain about 50 percent of the total SC population of the State. In many villages there are more than one Scheduled Castes localities. Though the SC population is found in all the districts of the State, the larger concentration of them in Ahmedabad, Banaskantha, Junagadh, Mehsana and Vadodara districts. According to the Government of Gujarat, this state-wide dispersal of the SCs makes it impossible to adopt an area based development approach for their economic advancement as has been possible in the case of the Scheduled Tribes.

More than 80 per cent of the Dalits in Gujarat are daily labourers, the majority of which are in the agricultural sector. Half of the SC population is landless or owns less than one acre of land, which forces them to work on dominant castes’ land in order to survive. Because of this dependence and the quasi-inexistence of labour welfare in Gujarat, Dalits are subject to immense pressure and utter discrimination. Atrocities committed against them are a daily reality, with more than 4,000 cases reported in the span of 3 years in just 14 districts. Manual scavenging is still very much prevalent also because the State’s institutions in Gujarat themselves employs Dalits to clean dry latrines. For a State that likes to depict itself as a modern and thriving region in India, Gujarat is still a far cry away from ensuring social justice to all of its citizens. In reality, Gujarat has a poor human rights record and must extend and focus its attention to its minorities if it is to be worthy of the kind of image it likes to give itself. Coming to the occupational break-up of the SC population, the 2001 Census data states that out of the 7.66 lakhs members of SCs classified as ‘workers’ in the 1981 Census, 3.15 lakhs are ‘agricultural labourers’ and 1.22 lakhs ‘cultivators’. About 0.40 lakhs are engaged in the household manufacturing and processing industries. 2.88 lakhs are listed as ‘other workers’ which includes the traditional occupations like weaving and leather-goods manufacture. 23 percent of the SC workers are women. In the manufacturing and processing industries only 5 percent of the workers are from the SCs. (Department of Social Justice and Welfare, Government of Gujarat)

Even among the SCs, there are wide socio-economic disparities between different castes-Valmiki, Hadi, Nadia Garo (Garoda), Turi, Harijan Bawa, Vankar Sadhu, and nine Senva communities being the most backward among them. These vulnerable communities, whose population is approximately 3.50 lakh are therefore singled out for the special treatment and exclusive schemes have been formulated for their benefit. (ibid)

History of Manual Scavenging in Gujarat

As per a report compiled on Manual Scavenging by The Tata Institute of Social Sciences in 2006, following are the kinds of manual scavenging peculiar to the state of Gujarat: Open Defecation, Gutter/ Cleaning of Open Drains, Water Borne Latrines, Khar Kuva/Shouch Kuva, Mechanised Cleaning of Sceptic Tanks, Dry Latrines (Dabba Jajroo/ Wada Jajroo/ Wadolia). The report talks about how the severe effects of scavenging on the health and hygiene of the manual scavengers leads to diseases like parasitic infections, gastrointestinal disorders, skin ailments, diminished vision and hearing due to the toxic fumes emitted from the manholes and sceptic tanks, and respiratory diseases such as breathlessness and consistent cough. The Valmikis or ‘Bhangis’ constitute a significant group among the Dalits and they personify the near inextricable links between their caste and occupation, namely scavenging and sweeping, which as has been talked about earlier, considered impure and polluting. According to the 1991 Census, the Valmikis constitute around 11.73 percent of the total Scheduled Caste population of Gujarat. (ibid)

The specific kinds of dry latrines in Gujarat have been described below:

The fact remains that the heinous act of manual scavenging has not received as much attention as it should have and there is still a long way to go for the complete abolition of this practice. In the sections that follow, a detailed analysis of the relationship between scavenging and its linkages with social exclusion, human dignity and value of labour within the context of caste shall be reached at.

Understanding the Issue within the Social Exclusion and Marginalisation Framework

This paper has dealt with the issue of manual scavenging and the lives and experiences of the community of people who were and still are involved in this kind of work within the framework of ‘social exclusion’ and how this causes marginalisation of workers from the labour market. The theory of social exclusion is the most appropriate theoretical framework to talk about this particular issue for more reasons than one, most of which shall be talked about in greater details in the pages to follow. Essentially, the theory of social exclusion brings out clearly the fact that there are very many groups or communities of people in society who are completely left out from the development process because of reasons embedded in the history of severe oppression and exploitation of these communities and reasons that decry any sort of logic or rationale of the so-called modern times. Social exclusion as a concept of social science has been talked about by many social scientists in the past, and hence it shall be important to lay the base and give a little bit of a background of how and why the concept arose in the first place, that is to say, the history of the concept of social exclusion which shall then be interlinked with the issue at hand. The term ‘social exclusion’ was first coined by Rene Lenoir in the mid 1970’s. According to Lenoir, the ‘excluded’ would include “the mentally and physically handicapped, suicidal individuals, aged invalids, abused children, substance abusers, delinquents, single parents, multi-problem households, marginal and asocial persons and other social misfits”. (Thorat and Newman, 2010). However, since these categories of people were in itself very exclusive, there was a need to recognise other groups of people within the categories of ‘excluded’, and hence later studies included groups of people who were denied ‘ a livelihood, secure, permanent employment, earnings, property, credit or land, housing, consumption levels, education, cultural capital, the welfare state citizenship and legal equality, democratic participation, public goods, nation or dominant race, family and sociability, humanity, respect, fulfilment, and understanding’. (ibid) What can be said is that social exclusion essentially means that a person or a group of people or a community is unable to participate in the most basic political, economic and social functioning of society due to varied reasons most of which are embedded in the inequalities of the social structure.

Furthermore, the concept of social exclusion can be extended to the labour market discrimination in hiring of employees. For instance, when two persons with similar employment experience, education, and training apply for employment, but because they differ in some non-economic characteristics, they face denial in hiring. These differences are related to certain non-economic factors like caste, class, gender etc. The problems of the safai kamgars fits into the social exclusion framework for many reasons. It is a well known fact that in India, exclusion has revolved around societal institutions that exclude, discriminate, isolate, and deprive some groups on the basis of ‘group identities’ such as caste, class, gender. The nature of exclusion associated with the institution of caste needs to be clearly conceptualised because it lies at the core of the developing equal opportunity policies, such as the positive discrimination or reservation policies that days back to the 1930’s. What is being explored through this paper is to reach an understanding of how the communities who have been engaged in manual scavenging work and now have made a transition to working in the sweeping and cleaning sector and are employed by the local government bodies, have their lives and experiences been in the employment sector and what are the kinds of hurdles and roadblocks they have faced because of belonging to a particular caste. An attempt has been made to develop an understanding of how caste discrimination has led to the social exclusion of the Valmiki Community people and also how the same has also become a major roadblock for them to achieve any sort of upward mobility in the job market.

In the course of the interviews conducted across the four districts of Gujarat, there were largely two perspectives that came through in the answers that the respondents gave when they were asked how they feel about being employed with the Municipal Corporations and Gram Panchayats in doing all the sweeping and cleaning jobs for so many years.

The first group of people belonged to the Valmiki Community and having been engaged in this sweeping-cleaning work for a many years, opined that they wished to leave this work and get into other sorts of ‘cleaner’ professions, where there would be no stigma attached to them because of their so-called ‘filthy’ and ‘dirty’ work and which provides them respect and dignity for their work. But the hugest problem that they have always faced is the fact that despite being educated till a certain level and despite applying to other kinds of jobs in private companies, they have always faced denial on part of the employers. And they firmly believe that this happens due to just one reason, that being, their caste. Being Dalits is in itself a burden for them, but above all, belonging to the Valmiki community, makes them prone to discrimination by not only the so-called upper castes but also by the so-called lower castes and other Dalit communities, many of whom treat them as untouchables even till today. The lack of any sort of alternative livelihood opportunities forces them to stick to the conventional caste-based occupation that they have been ascribed to since time immemorial. The forms of perpetuation of exploitation and discrimination have changed but the very rudiments of the same remain intact. The Valmiki community people were always socially excluded from the development discourse and they still have to go through the same webs of oppression.

The second group of people who belonged to the Valmiki community and engaged in this kind of sweeping-cleaning work refused to let go of the broom from their hands. In fact, the argument offered by this particular group was the fact that these cleaning-sweeping jobs should be reserved solely for the Valmiki community since they have been involved in this work since centuries together, since the time when they have had to do the dirtiest of the dirty jobs, like carrying human excreta on their heads and cleaning private dry latrines of the upper castes. Now that this has been banned, and some bits of technology is coming into the picture for the cleaning-sweeping works, they feel that other Dalit communities like the Chamars (Rohit-leather workers), Vankars (weavers) are coming into this work thus snatching away opportunities that should ideally be reserved only for them. They expressed their anger on the government that is allowing the other Dalit sub castes to intrude into their work. Instead, this lobby suggests better wages, better working conditions, making the workers permanent, and providing all government facilities and perks like Provident Fund, House Rent Allowance etc. should be made available to them.

A third lobby of people, not belonging to the Valmiki community, opine that the Valmikis do not want to leave the cleaning-sweeping work because there are a lot of attached ‘benefits’ that they get alongside their wages/payments. On asking for further clarifications, they would say that the safai kamgars never cook at home because they always get stale food from the houses/colonies where they work in. They also do not have to buy any clothes for themselves because on festivals they get old clothes from the same people who consider charity to be a noble thing to do. This came across as quite an interestingly amusing viewpoint and the most interesting part of this story was the fact that the group of people who held this viewpoint were mostly all Non-Valmiki Dalit sub-castes. This not only fits in perfectly within the social exclusion framework, but it also brings out a newer perspective of how the Valmikis are excluded from development by fellow Dalit communities. Social exclusion also depends much on the ‘perceptions’ of people about certain communities. While conversing with the non-Valmiki, Dalit communities who put forward this perspective, there was clearly a certain degree of animosity and a desire to keep the Valmikis as far away as possible from the benefits of development that the other communities have been able to access. The significant question that arises here is this: can thought processes not lead to social exclusion and marginalisation and can the same community not lead to social exclusion of people from amongst themselves, who have got left behind in the processes of development due to various reasons? What role does the psyche play in leading to an understanding of how social exclusion operates at the intra-caste levels, like the instance just cited above. These are important questions that need to be answered in the social sciences academia.

Interestingly, there is one common underlying factor that all the three groups of people mentioned above talk about; that is, the fact that it is almost next to impossible for the Valmiki community people to move towards any other occupation once they have been involved in the cleaning sweeping work. Infact, even if they have never been a part of the so-called ‘dirty’ work, the mere fact that they belong to this particular sub-caste becomes a hindrance for them to even aspire for anything different in the job market. A popular belief about the caste system in India is that the present day inequalities are a result of past discrimination, primarily confined to rural areas. The notion is that labour markets in urban areas, especially in the formal private sector, are essentially meritocratic. Also, another view attached to this is that given the difficulties in identifying caste in the relatively anonymous urban settings, the bulk of the caste discrimination occurs mainly in the rural, traditional parts of the country. (Deshpande, 2010: 433) However as is being talked about in this paper, and as more evidence shall be provided, one shall have to acknowledge the perpetual presence of the caste structure in society which in turn perpetuates discrimination of various kinds.

Important to note here is the fact that some of the participants of the interviews conducted during the process of the study have never done the sweeping cleaning work in their entire lives.

It would be pertinent to bring in the response of one such respondent, Nattubhai (name changed) who is a mason and whose father worked as a carpenter. Nobody in their family has ever ‘touched a broom’ (as he put it), thereby never having done ‘safai kaam’ in their lives. Nattubhai’s story was indeed very interesting as he spoke strongly against the Valmikis’ involvement in the sweeping-cleaning work. According to him, as long as the people of their community continue doing this work, there would be no end to their oppression and exploitation because it is their work that leads upper castes and other Dalit sub-castes to discriminate against them, and treat them as untouchables. When asked whether he faces any discrimination in his present work as a mason, he replied in the positive.

“Yes, there is a lot of discrimination against the Valmikis, and this is everywhere…where and how do you think we would be free from this curse…belonging to this jati is itself a burden for us, but I know that if we give in, we would have to suffer all our lives and worst of all, our children would have to bear the brunt of this oppression. I do not want my children to be discriminated against, like me, and I want to give them a bright future, far away from the horrors of being treated as untouchables…change will take time, but I know it will come, and my children will see brighter days when they grow up..”

He further added that for him, it was easier to make a choice of not engaging in their conventional ‘caste-based occupation’ of cleaning and sweeping because his father had already made that choice by working as a carpenter. However, Nattubhai had his own stories of discrimination and oppression, and as he spoke, we silently heard and understood some basic issues of how engaging in caste based occupation is only one way of perpetuating oppression, violence and exclusion. His masonry work is restricted to making houses of other Dalit sub-castes like the Chamars, Vankars and of course, those of his own caste, Valmikis. He said that the upper castes like the Durbars and Rajputs never call him for work at their houses and moreover, even if they did, he would not care to even look at them, because they still treat them as untouchables and behave in an improper manner with them. According to Nattubhai, the Valmiki people have to be made aware of their self-respect and they have to consciously decide to stop working in places where they are treated as lesser human beings. He had made this decision long back, and still stands by the same. For him, he is as human as the Patels, Durbars and the Rajputs and nobody has any right to degrade him just because he is a Valmiki. He calls the sweeping-cleaning work as ‘slavery’ and vehemently opposes the involvement of the people of his community in this work. It was important to put across what this person had to say about the work that has been ascribed to the Valmiki community as a caste based hereditary occupation, not only because he has not been a manual scavenger or a safai kamgar ever, but mostly because he is an integral part of the Valmiki Samaj and feels very strongly for his own community.

However, Nattubhai’s story puts across another important question, that being, is it really possible for the people in question to ‘leave their brooms’ and get other work? The answer to this question came from many of the other participants of this study, who found this question ridiculous in the first place. The fundamental characteristic of predetermined and fixed social and economic rights for each caste, with restrictions on change, implies ‘forced exclusion’ of certain castes from the civil, economic and educational rights that other castes enjoy. In the market economy framework, occupational immobility would operate through restrictions in various markets and include land, labour, capital, other inputs and services necessary for pursuing any business or educational activity. (Thorat and Newman, 2010) When asked about whether they would like to leave their brooms and get employed elsewhere, most of the participants of the study scoffed at us. A later realization was that this question was in fact rhetoric in nature for them and as one of the respondents answered,

“we don’t dream so big and are happy doing what we have always done…if you can help, please try and ensure that our wages increase, that we are made permanent, that our work conditions improve and we are able to lead a decent life, just like you all…”

What comes across from this is the fact that for the manual scavenging communities, it is difficult to even imagine getting other forms of employment opportunities. Not that they have not tried.

Many of the respondents told us that they were High School passouts and some had even completed their graduation, having endured much difficulty at home. However, they still work as sweepers-cleaners at the Municipal Corporations. When we talk of lack of upward social mobility, especially in terms of economic opportunities, this is what we mean by social exclusion. Jagdishbhai (name changed) is a graduate, and is working as a safai kamdaar in Mehsanna District’s, Kadi Block. When he had set out to look for alternative employment in private companies, some seventeen years back, he was either rejected everywhere, or was offered jobs of supervising toilet cleaning jobs. His education was not valued anywhere and all that people saw was that he belonged to the scavenging community which made him best suited for the cleaning-sweeping work. This constant harking back to the ascribed occupations of the so-called untouchables is a major roadblock to their upward mobility in terms of occupation and access to economic resources.

This leads us to question the importance of education in the Valmiki community. Many of the participants of the study displayed utmost indifference towards the importance of education for their children, which seemed like a cause of concern. This of course has a history to it. For many of the respondents, the importance of education has reduced over time because of bitter personal experiences. Many of the participants of the study argued that higher education has no meaning for them because despite reaching there and successfully completing their higher education, they cannot access the job market like other people, and there exists a tremendous bias against their caste till today.

Thorat and Newman’s definition of caste based discrimination throws light on the situation of the people belonging to the scavenging community and it theorises the discrimination in the economic sector. There are four kinds of caste and untouchability based discrimination that they have talked about:

a) Complete exclusion or denial of certain social groups such as the lower castes by the higher castes in hiring or sale and purchase of factors of production, consumer goods, social needs like education, housing, health services, and other services transacted through market and non-market channels, which is unrelated to productivity and other economic attributes.

b) Selective inclusion but with differential treatment to excluded groups, reflected in differential prices charged or received.

c) Unfavourable and often forced inclusion bound by caste obligations and duties reflected in overwork, loss of freedom to work leading to bondage, and attachment ; and also reflected in differential treatment at the workplace.

d) Exclusion in certain categories of jobs and services of the former Untouchables or SCs who are involved in so-called ‘unclean or polluting’ occupations. This is in addition to the general exclusion or discrimination that persons from these castes would face on account of being untouchables. (Thorat and Newman: 8-9 2010)

All of these four kinds of caste based discrimination is practiced against the Valmikis of Gujarat, in fact, some of them in their extreme forms. It is important to understand that exclusion and discrimination against the Valmikis has only changed its shape and form, instead of disappearing completely. This is what we shall be explored in the following sections of the paper.

Valmiki Women: Intersecting Webs of Oppression

Having briefly talked about how social exclusion functions for the people belonging to the Valmiki community because of them being members of a so-called lower caste and being ex-untouchables, I would now bring in the concept of intersection of caste, class and gender and try and develop an argument about how exclusion from the mainstream development discourse is worse and comes at a much heavier cost for women belonging to the Valmiki community. The maximum numbers of manual scavengers was and are still women. What has come through very clearly through this study, is the fact that the women who have been involved in manual scavenging have faced oppression at much higher level, essentially because they are in a situation of double bind, being oppressed being a part of the Valmiki community and also being women of the same community. Majority of the people who work as safai kamgars are women. When the dry latrines and wada jajroos were still in use and were not prohibited by law, most of the manual scavenging work of cleaning up of human excreta by their hands was done by the Valmiki women, because the dry latrines and wada jajroos were used by women only. The private dry latrines were used by women of the upper caste (mostly Darbars, Rajputs, and Patels) since they were not allowed to go out of their homes and had to practice the ojhal pratha (veil). Hence most of the filthy work was and still is done by women of the Valmiki community.

This has a direct impact on the health of these women and also the health of other family members, especially small children, who the mothers are closest to physically. According to all the participants of the study, none of the Municipalities provide them with the required safety equipments like masks, gloves, uniforms, antiseptic soaps to wash their hands with, etc. This makes them prone to various illnesses. This double oppression of the Valmiki women is not restricted to the fact that the most dangerously filthy work was and still is done by the women. They are also vulnerable to various forms of sexual exploitation at the places they work in, and are constantly under threat of being exploited and oppressed. In Surendranagar District, one of the participants of the study narrated an incident which truly captures the situation of the Valmiki women that is being talked about here. She works as a cleaner in the Municipal Corporation and apart from that also works as a private cleaner at people’s homes, for which she gets paid very less, but whatever little she earns is an additional income nonetheless, and hence she does engage in some private cleaning work, mostly in the homes of the upper castes-Darbars and Rajputs. According to the respondent, a few days ago, she did not go to work at the house of a Darbar family since she was unwell. In the meanwhile, she was summoned by her employer and was asked to come to work. Despite many refusals, she was forced to go to his place, and when she went inside the house, the man made unwanted advances at her, in reaction to which, she hit his face and ran away. She said that this person was behaving a little suspiciously since quite a few days in the past. They have filed an FIR against the employer, but she says that there is little hope since he is an upper caste and is loaded with property and money, and for a Valmiki woman, it is extremely difficult to fight against upper caste men. The condition of the women engaged in safai kaam is thus much worse than their male counterparts.

The scavengers and sweepers-cleaners are an invisible lot in these four districts of Gujarat, and despite being the reason behind why developing Gujarat is able to showcase a ‘clean’ face to the world, the communities and localities where the Valmikis live are always surrounded by open drains, and consequently with filth, and disease carrying flies and mosquitoes. According to Pattubhai (name changed) from Mehsana District,

“We ensure that people are able to live in clean environments, and work day and night to clean up localities and housing societies for which we don’t even get paid properly…but look at the condition of our localities. Nobody is assigned the work to clean our localities..it is almost as if we don’t even exist for the Nagar Palika…we live or die, nobody really cares..we will always be called Bhangis by other people and we will never be given any respect for the work we do, for the fact that it is because of us that you can sleep peacefully without the stench of urine in your locality, that you are healthy and don’t fall sick as often as we do…”

‘Asprishyata’ : An Unending Trauma for the Valmikis

Untouchability is not merely the practice of not touching other human beings because of their lower-caste status. It is a highly loaded terminology for a completely unscientific and irrational practice that has its roots in the Caste System. Despite the Constitution of India having abolished the practice of untouchability in the year 1950, one of the most important and startling findings of the current study was the continued existence of untouchability being practiced against the scavengers or Valmikis in the state of Gujarat. Undoubtedly, the forms and means of its perpetuation has changed over the years, but the people from the Valmiki samaj still occupy the lowest rungs of the hierarchy as far as the caste structure is concerned. It is also important to understand that the role of religion in perpetuation of caste discrimination is the most significant. All the participants of the study were followers of Hindu religion and practiced their faith with utmost sincerity. However, most of the respondents told us that they continue to face discrimination of severe forms, which if studied carefully, would translate into forms of untouchability.

The most frequently stated form of blatant untouchability would be not allowing the Municipal Corporation and Gram Panchayat ‘safai kamgars’ to drink water from the glasses used by the so-called upper castes. While working if the sweepers would feel thirsty, they would not be given water in any of the utensils (glass, tumbler, pot) owned by the upper-caste. Water is poured from a height and the sweepers have to cut their hands and water is poured from a height for them to be able to drink water. Sometimes, they are denied water outright and have to go thirsty all day during work hours. This is extremely humiliating for the workers since they are not treated as equals in any manner, and most believe that it is due to the nature of their work that they are discriminated against in such humiliating manners.

In most of the villages, Valmikis are not allowed to enter the temples of upper castes and they have their own temples where they worship Hindu gods and goddesses. The irony of the situation remains that the scavengers are still practitioners of the Hindu religion, barely any of them have been able to come out of the folds of this religion and its oppressive structures.

There are clear demarcations in the terms of geographical locations of the housing of the scavengers. The living conditions of the Valmikis are much poorer than people belonging to other communities. What came out very starkly through this study was the fact that the living spaces of this group of people are terrible and despite ensuring that other people living in clean environments, the surroundings of a typical Valmiki Basti in Gujarat would invariably be covered in filth and open drains, which lead to spread of various diseases like malaria, typhoid, dengue, cholera etc. Most of the Valmiki Bastis are at the outskirts of the city or at the periphery of the village.

It is important to understand the issues that the Vakmiki children face because of their caste identity. Although, understanding children’s issues was not an objective of the current study, during the course of the interviews, many shocking realities emerged which became important data to understand the effects of manual scavenging on the Valmiki community as a whole. During one of the interviews in Mahudha Block of Kheda District, we happened to come across a few school going Valmiki children who revealed some very shocking facts about their lives and conditions, which in turn weaves an important theoretical framework about how social exclusion operates within the caste structure. According to Param (name changed), a student of standard 7 th said that he helps his mother in scavenging work every morning because his mother has been keeping quite unwell in the recent past. His daily routine is such that he gets up 5:00 a.m. and goes out to sweep and clean the roads and other localities after which he leaves for school. In the evenings also, he sometimes, engages in sweeping and cleaning work. He also manually cleans open drainages and in the process sometimes he has a severe backache and breathing problem and pain in this chest, but he has not told his mother about the same, because as it is his mother doesn’t want him to work in this sector, he does this ‘only for the sake of my mother…I cannot see her cleaning roads and gutters when her health condition is so poor.’ Shockingly, he also said that sometimes they are made to clean the excreta of small children, and when they refuse to do this kind of work, the supervisors tell them that it is animal excreta and make them clean the same nonetheless. Also, all the work of carrying away carcasses of dead animals is done by the Valmiki children. The fact that social exclusion from the structures of justice and equality does not remain restricted to adults and permeates into the lives of children and affects their impressionable lives is what has to be understood here. When asked what kind of work he would like to do in the future, he remained quiet for a bit after which, staring blankly into nothingness, replied that he doesn’t have much choices; if he gets some work other than sweeping-cleaning, he would be happy to do that, otherwise he already knows how to sweep the roads, it wouldn’t be much of a problem to take over his mother’s work at the Nagar Palika. The fact that a fourteen year old child engages in cleaning of filth and does not think he can escape the vicious cycle of caste exploitation itself explains the fact that the webs of oppression are deeply ingrained in society, and nothing less than an overhaul of the Brahminical caste system would bring them out of this condition. However, there were a few highs in Param’s story. Since 2009, caste based discrimination has indeed reduced and their forms have become less brutally visible; this change could be attributed to the work of the non-government organisation called Navsarjan Trust based in Hyderabad, that has been working in this sector for the improvement of the conditions of the Dalits, especially the Scavenging Caste or the Valmikis. On August 16 th, 2009 Navsarjan Trust had conducted a huge rally for bringing visibility to the issue of manual scavenging, in which many children from the Valmiki community had participated and from then to today, the levels of discrimination and untouchability have diminished in the public spheres like schools. Unlike earlier, when they were not allowed to sit in the classrooms with the children of upper caste families, were made to clean toilets in the schools, were made to sweep the classrooms and school grounds; today they feel much safer in school and such blatantly evil forms of discrimination are not practiced anymore.

Discrimination and practices of untouchability, rather a mentality of maintaining status quo can be understood through non-verbal methods of communication as well, for instance, in idioms of daily use, jokes that are cracked, and phrases in literature as well. This brings us to another incident that took place during the process of data collection for the purpose of this study. In Ahmedabad district’s Dholka Block, the study team was looking for the Valmiki colony near the Municipal Corporation office, but despite wandering about the whole area for a long time, we were unable to find the exact location of the Valmiki colony where we were suppose to conduct interviews. In the process of this vigorous search, we asked a few women about directions, to which, initially they merely smirked and later asked us what work we has in the ‘Bhangi Awas’, had we come to sell some schemes for the ‘Bhangis’ and this statement was followed by a roar of laughter from all the people in the house and their neighbours who had heard our conversation.

During an interview in Matar Block of Kheda District, one of the participants opened our eyes to a wide range newer forms of discrimination and untouchability when he brought out the issue of refusal to rent out houses to educated Valmiki community people by upper castes in cities in Gujarat. A young Valmiki woman from Kharati village, in Matar Block, works as a school teacher in a government school. Since the distance between her village and her workplace is 15 kms one way, she is required to travel 30 kms to and from work, and hence she was looking for a room on rent near her workplace. However, she had to face blatant refusals because she belonged to the scavenging caste. And these refusals happened not only by the upper castes but also by other Dalit sub-castes. She is left with no choice but to travel such a long distance. Another similar incident wherein a Valmiki woman had to quit her job as a teacher in a government school in Kuchh because she could not find a place to stay, since nobody agreed to rent out a room to her, and it was not possible for her to travel from Kheda to Kuchh every day. The question that arises here is what kind of changes have occurred in the societal structures wherein despite achieving a high educational and economic status, ones’ social status remains completely unaltered, and discrimination based on this social status continues till date.

Interestingly, the other Dalit sub-castes like the Chamars (Rohit), Vankars etc. although not much better off than the Valmikis economically, discriminate against the Valmikis and also practice untouchability against them, thereby proving again and again that they are located at the bottom of the caste hierarchy, even amongst the Dalits themselves. Discrimination and perpetuation of oppression has such deep roots in the structure of society, that even amongst the same caste who were treated as Untouchables at one point in time, there are layers that perpetuate the same wrongs against groups that are still lower than them. This is a perfect example of how social exclusion becomes a part of the psyche of the dominant and being excluded becomes almost like a habit for the socially marginalised and downtrodden.

Work and Labour of the Valmikis: Is the Ordeal Over Yet?

With the passage of the Acts prohibiting manual scavenging in 1993 and another Bill having been introduced in the Parliament as recently as 2012 regarding the rehabilitation of Manual Scavengers, an attempt was made in this study to understand whether there have been any significant changes in the lives of the Valmiki community people who were involved in this obnoxious ‘occupation’. What was found in the study was that most of the people of the Valmiki community are still engaged in scavenging, sweeping and cleaning work and are employed by the Municipal Corporations of cities and Gram Panchayats. There have been two schools of thought that talk about the caste based occupational structure and both these schools hold opposing views regarding the same. The first school of thought talks about the fact that caste not only prescribes for each person a hereditary occupation but also discourages his/her attempts to surmount the occupational barriers existing for his/her group. Subscribers to this view recognise that absolute immobility in occupational status, horizontally or vertically, is practically impossible within this caste structure, and they also contend that in India fixity reaches such a point that is harmful to economic development. The contrary viewpoint is one that talks about how this rigidity in the caste structure with regard to hereditary occupations was present in the past, but things have changed in the modern times and social and occupational mobility is truly possible. (Driver, 1962)

However in the case of the Valmikis of Gujarat, the latter does not hold good at all. There are innumerable problems that the safai kamgars have to face in this kind of work, and although none of them are directly involved in cleaning and disposing human excreta anymore, their dignity of labour is still under constant threat. The fact that caste based occupations can in fact become major indicators of which work in clean and pure and thereby the fact that the people engaged in the same deserve to be accorded the dignity of their labour, while other kinds of work like scavenging, leather works, tanning are considered impure and polluting, thereby, not deserving any sort of respect for their work. The caste based occupation is a clear question mark on social mobility and about a person’s right to dignity of labour. The fact that scavenging as an occupation has been looked at as hereditary and generations of Valmikis have been involved in the same occupation, unable to have switched to other professions; this shows the oppressive nature of the concept of caste based occupations. The upper-castes can switch to better professions but of course never climbing down the ladder of caste based occupations to start doing work that is below their ‘dignity’. Similarly, the lower castes remain stuck in their ‘unclean’, ‘impure’ and ‘polluting’ jobs, never being able to climb up the caste ladder to start doing jobs that the so-called upper castes have had their hold on. This rigidity of the caste structure leads to the exclusion of these groups from the mainstream development discourse, thereby putting a big question mark on the whole process of development.

The conditions under which the safai kamgars work are indeed worrisome. The lack of any safety equipments for the safai kamgars involved in sweeping and cleaning of public roads, private housing societies, cleaning of open manholes, gutters and sewers increases the vulnerability of the safai kamgars. Although it is mandated by law that they should be provided with equipments like an uniform for work, hand gloves, masks to cover their faces, antiseptic soaps for washing hands and the instruments for cleaning like long-handled broomsticks. However, none of these safety mandates are followed by the Municipal Corporations and all the work is done by the safai kamgars with their bare hands. In many of the Municipalities and Gram Panchayats, even the broomsticks are not provided and the kamgars have to make their own broomsticks at home, for which they are paid nothing at all, and which they then take to work.

Coming to the types of workers and the wages for the same, there are essentially three kinds of workers in the Municipal Corporations of Gujarat. The first and the least in number are Permanent Workers of the Municipal Corporations of various cities, and they get paid around Rs. 4800 per month as their wages o top of which they also get Medical allowances worth Rs. 100, House Rent Allowance worth Rs. 240, Provident Fund worth Rs. 1032, and PF Loans worth Rs. 1100. However, in the course of this study, we came across only 3 people who are permanent employees of the Nagar Palikas.

The rest of the workers/ safai kamgars come under two major categories; Daily wage worker (Rojamdaars) who get paid around Rs. 187 per day and Contractual Workers who get paid around Rs. 124 per day. The workers who come under the category of Rojamdaars are in the majority in the Nagar Palikas of the Districts where this study was conducted and they are the most oppressed lot of the workers. There are kamgars who have been working in the Nagar Palikas since the last 30-40 years and are still working as daily wagers. There are innumerable issues with the daily wage workers in the Nagar Palikas. First and foremost is the fact that their wages are much less than the permanent workers and it is highly unfair that despite working for such long periods of time, these workers do not receive any social security benefits that workers in the organised sector are entitled to. The other most important issue with regard to this category of workers is the fact that they live in a sense of constant fear and insecurity of being suspended or thrown out of work on petty pretexts like taking leaves when they fall sick, coming even as much as 10 minutes late to work, arguing with the supervisors, refusing to work beyond their area (vistar) of work, essentially all such situations which would otherwise have been taken for granted as their entitlements if they were permanent employees of the Municipal Corporations, become sources of fear and insecurity amongst the daily wage workers and they are not able to protest and raise their voices against these injustices, lest they lose their jobs. The wages of these workers are held up for months together, which leads to an aggravation of the situation at their homes and compels them to take up private work, which is again a different story of exploitation altogether. Making both ends meet becomes a problem, ‘how do you expect us to educate our children, when we don’t even earn enough money to feed them properly?’ says a respondent from Limbdi Nagar Palika, Surendranagar District.

Another grave issue is the lack of mechanisms for raising their voices against the injustices happening against them. The fact that the largest majority of the people are daily wage workers and thereby non-permanent, takes away their voices to protest against the wrongs in the system. However, even if there are some people who go out to protest against and oppose the current state of affairs, and for instance, sit for a dharna, refusing to work, there are lots of people available to take their places. This lack of unity amongst the Valmikis should be seen through the lens of economic compulsions that they live under. And this sense of economic insecurity does not allow them to come out and raise their voices.

Also the supervisors of the safai kamgars, are many a times, non-Valmki Dalits, like Vankars and Rohits, or sometimes could also be Non-Dalits like Bharwads (an OBC caste, mostly landed). This leads to a clear hierarchy between the kamgars (all of whom are Valmikis) and the supervisors (many of whom are non-Valmikis), which in turn leads to confrontations and exploitation of the kamgars, who are often verbally abused for not working properly, not agreeing to do extra work, etc. Valmiki women bear the brunt of their caste ever more than their male counterparts.

People who do contractual work are even worse off because the contractors ill-treat them and they cannot even go to the Nagar Palika to lodge complaints about such ill-treatment. They get paid either equal to or lesser than the daily wage workers in the MC’s, but there are other additional problems of harassment in this kind of work. One of the respondents, from Limbdi Block, Surendranagar district, brought out a problem that they have been facing since a long time. The Muster Rolls (attendance sheets) of the workers is kept at the block MC, and although there is no connection of the contractual workers with the MC in any other way, the kamgars have to travel to a place 3 kms away from their area of work to sign in and sign out, once in the morning, then in the afternoon and then again in the evening. This is extremely harassing for the workers, especially the women kamgars, since they either have to walk this distance of 9 kms everyday and being late to work is absolutely not tolerated, or they have to take rikshawa where they have to shell out at least Rs. 50 per day for travelling. Despite telling the contractors about this problem, they have constantly turned a deaf ear to the pleas of the safai kamgars.

Apart from working under the MC’s , Valmikis also engage in private/unorganised sector work like sweeping and cleaning work in private housing societies, cleaning toilets in private hospitals and dispensaries, sweeping and cleaning in factories. Valmiki men and women are not allowed to step inside the houses of the upper caste people and hence the prospect of domestic work in other people’s houses does not exist. Also, there is no regulation of the kind of work that they are made to do in the private-unorganised sector.

One such stark and gory story is of Ratnaben (name changed) who lives in Changodara village located in Sanand block of Ahmedabad District. A woman of around 35 years of age, she lost her husband while he was cleaning gutters for a private Biscuit manufacturing Company, five years ago. He could not survive the poisonous gases emitted from the drains that led to his death. Although a meagre compensation was paid to Ratanben after his demise, the amount got over very quickly in fulfilling her family’s daily requirements. Today she struggles to send her four children to school, out of which the eldest daughter has already dropped out and helps her mother in collecting cow-dung from all upper caste houses in the village. There are days when they have to go to bed empty stomach because the money that they get out of cleaning the cowsheds does not give them enough to even manage two square meals a day. The company that her husband worked for has never contacted Ratanben after her husbands’ death. She is constantly harassed by her in-laws for property issues and they threaten to throw her and her children out of the house if she does not surrender part of her daily income to them. Her life is indeed precarious and a daily struggle for survival. She has tried to get work as domestic help in the houses of people in housing societies in Sanand, but the moment people get to know that she is a ‘Bhangi’, they refuse outrightly to even let her enter their homes. The burden of caste based social exclusion is so much more and is felt by her every single day.

Remnants of ‘Manual’ Scavenging

After a survey conducted by the TISS in 2006 in Gujarat, all the dry latrines was demolished and it was said that manual scavenging has come to an absolute end after the same. Though it is true that most of the dry latrines in people’s houses like the dabba jajroos and non-dabba dry latrines were broken down, there are still many places where the ‘wada-jajroos’ exist and are in use and still cleaned by the Valmiki women. However this does not happen openly, since the local authorities would come under the scanner if this came into the open. We were able to locate these wada-jajroos in at least two places during our data collection. The first was in Kharva Gram Panchayat, Wadhwan Block in Surendranagar District of Gujarat. Here the wada-jajroo was in fact recently constructed by the Gram Panchayat in the year 2005, surprisingly under the government scheme called the Jawaharlal Nehru Urban Renewal Mission (JNURM). This is in gross violation of the Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act, 1993 which has banned the construction of all kinds of dry latrines in the country. It had also ordered for the demolition of all dry latrines so that the inhuman practice of manual scavenging is abolished altogether. However, the presence of the Wada-Jajroo in the said Panchayat shows that there are still many places in Gujarat where this heinous activity continues, although the local authorities deny the fact that the wada-jaroo is cleaned by the Valmikis. It is not cleaned on a daily basis, but whenever it is cleaned, the people from the Bhangi Awas are employed to do the same.

Another Wada-Jajroo was located in Khichdisera Colony, Dholka Block in Ahmedabad District. The Wada-jajroo is still in use and is cleaned by Municipal Corporation employees from the Valmiki community. It is indeed a disgrace that despite the passage of the act to prohibit the same almost two decades back, the prevalence of the same continues to inflict the trauma of manual scavenging on the said community. Also, the fact remains that due to the lack of proper public toilets and their inadequate capacity of accommodating so many people in a toilet with just 3-4 seats leads to open defecation outside the public toilets which has to be cleaned up by the safai kamgars. If all of this is still happening, how does one hold up one’s head and say that manual scavenging has disappeared from Gujarat and the rest of the country.

Also most of the manual scavenging happens either very early in the mornings before sunrise or very late into the nights, so that they do not come under the scanner of the police or civil society activists.

The scavengers’ lives remains a gory reality of underpayment (not even getting wages as per the Minimum Wages Act), working in filthy conditions, cleaning the whole city’s filth and yet living in areas which are the most unhygienic and the filthiest in the whole city, and of course, living in constant psychological trauma of caste discrimination and untouchability.

Conclusion

The usage of manual labour of the people belonging to the lowest of the lower castes not only dehumanises their labour, but also puts a big question mark on the value of labour in a country and a state that claim themselves to be in a position of sky rocketing development. The mechanisation of such scavenging activities and the complete rehabilitation of the people of the Valmiki community involved in sweeping-cleaning work is the need of the hour. The activists of the Navsarjan Trust who guided the whole process of this study by providing their complete help and co-operation everywhere and helped us in understanding the issue much better, are of the view that until and unless the Valmikis of Gujarat do not leave their brooms and take up other, more respectable work, where their labour would be valued much more. The questions then arises as to how far this shift is possible since we have already talked about how occupational mobility for this community is not only difficult but next to impossible in most cases, since they are completely excluded from the mainstream socio-economic and political structures of society. They have never been given a fair chance and it would require much efforts on the level of the government in terms of policy making so that they can leave their caste based occupation. Rehabilitation is the need of the hour. Navsarjan Trust’s Dalit Shakti Kendra located in Sanand Block of Ahmedabad district provides vocational training to Dalit youth, and many of them have in fact been successful in starting their own small ventures and have left scavenging work for good. Some of the respondents of this study have been successful in setting up tailoring shops, mobile repair shops, becoming apprentice carpenters, masons etc. after getting trained in the Dalit Shakti Kendra, and are quite happy at having left the degrading scavenging work. However, there are also people who have not been successful in switching to other kinds of work despite having received training at the DSK, and they continue to be engaged the sweeping-cleaning work that they did earlier. Rehabilitation is not easy at all because the stigma attached to the scavenging activity continues to haunt them and other people refuse to avail of their services if they get to know about their caste backgrounds. A systematic pattern of social, economic and political exclusion does not allow them to become a part of the mainstream development discourse.

It is quite surprising that despite such immense claims of a ‘Nirmal Gujarat and Suvarna Gujarat’, why a certain section of the population has been left behind in partaking the benefits of the ‘nirmalta’ and ‘suvarnata’ of the ever so rapidly developing state.

Unionisation amongst the safai kamgars and developing organic leadership amongst them would go a long way in demanding and acquiring justice for the Valmiki community as a whole. The problem remains, as stated by many of the participants, that there is no unity amongst the community themselves which nullifies all attempts at getting them together and mobilising them to give them the space to raise their voices and bring out their problems in the public arena, since the problems and issues of these people are as invisible as the community itself. There are indeed deep divisions within the Dalit community itself, which leads to further fragmentation and lesser understanding of the Valmikis since many a times they are subsumed under the larger umbrella of Dalits.

Of course, provision of better infrastructure in terms of provision of flush toilets in villages has to be taken care of, since till today, majority of the country’s population does not have access to proper sanitation facilities.

The lives and experiences of the people from the Valmiki community remains a story of trauma, oppression and lack of dignity of the individuals and their work and labour. As has been talked about earlier in this article, exclusion operates through social and economic practices, and in turn leaves the community out of the development discourse of the state. Despite laws about the prohibition of manual scavenging and the rehabilitation of manual scavengers, what has emerged from this study is the fact that the implementation of these laws has been really superfluous, making a joke out of the laws in a certain sense. The lives and experiences of the Valmikis goes to show how difficult survival is, even for the people engaged in the organised sector (Municipal Corporations and Gram Panchayats) as also for the for the people engaged in the unorganised sector, like private factories, dispensaries, hotels-since the work that they do is restricted to sweeping , cleaning and scavenging only. The chances of upward social and economic mobility are extremely low and the reasons for the same have been discussed in detail in the paper. What one has to understand here is that the caste based occupation structure is so rigidly implanted into the psyches of the people, that rationality and logic fail to drill scientific sense into them and thereby, people refuse to accept the fact that people who have faced injustices historically have every right to climb up the social ladder and make their presence felt in the labour market. The continued existence of varied means and forms of untouchability practiced against the Valmikis is also a significant finding of the current study. The current paper has looked into their lives from the lens of social exclusion and how it leads to a lack of dignity of the individuals and their labour. Undoubtedly, the lives of the Valmikis of Gujarat seems to be in a transitional phase, where some members of the community are quite sure about leaving the caste based occupation that they have been stuck with for the past many generations, but there innumerable hurdles for them to even think about the same, since switching to alternative means of livelihood is next to impossible for them because of the biases existing the labour market. On the other hand, some other members of the community want to stick to this caste based occupation, because they think since this is something they have always done and they should in fact be the only community doing this kind of cleaning-sweeping work, and the conditions of work should be improved, so that they can avail of the social security schemes of the Government. The latter group of people also think that this kind of work should be reserved solely for the Valmikis and other Dalit communities should not be allowed to come into this occupation. However, even in this case the reason for such vehement advocacy for reservations also arises from the fact that there aren’t any alternatives that the Valmikis can bank upon. Their lives and experiences tell a story of continued exclusion from a life of dignity that the Indian Constitution has promised to every citizen of this country. What many advocates of the rights of the scavenging community have been suggesting is a complete rehabilitation and liberation of the Valmikis from this life surrounded by filth and dirt, without any sense of security of life. Their lives have to be understood through a lens of intersectionality between caste, class, gender, and human dignity; only then would one be able to get a holistic perspective of how social exclusion has functioned over centuries for the Valmikis of Gujarat.

Bibliography:

Burra, Sunder, Patel, Sheela and Kerr, Thomas. October, 2003 “Community-designed, built and managed toilet blocks in Indian cities” Environment and Urbanisation, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 11-32

Darokar, Shailesh and Beck, H. September 2006 “ Study on the Practice of Manual Scavenging in the State of Gujarat” A Report Compiled For the Gujarat Safai Kamdar Vikas Nigam (A Government of Gujarat Undertaking)

Darokar, Shailesh Kumar and Beck, H. April, 2005 “Socio-Economic Status of Scavengers Engaged in the Practice of Manual Scavenging in Maharashtra” The Indian Journal of Social Work, Volume 66, Issue 2

Deshpande, Ashwini. 2010 “Merit, Mobility, and Modernism: Caste Discrimination in Contemporary Indian Labour Markets” The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, Vol. 53, No. 3

Donelly, Jack. June 1982. “Human Rights and Human Dignity: An Analytic Critique of Non-Western Conceptions of Human Rights” The American Political Science Review, Vol. 76, No. 2, pp. 303-316

Driver D., Edwin. October, 1962 “Caste and Occupational Structure in Central India” Social Forces, Vol. 41, No. 1, pp-26-31

Howard E., Rhoda and Donnely, Jack. September, 1986 “Human Dignity, Human Rights and Political Regimes” The American Political Science Review, Vol. 80, No. 3, pp. 801-817

Khurana, Indira and Ojha, Toolika. October, 2009 “Burden of Inheritance” A Report by Water Aid

Killen, Melanie. Feb 2007 “Children’s Social and Moral Reasoning About Exclusion” Current Directions in Psychological Science, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 32-36

Massachussets Institute of Technology (MIT). September 2006 “From Promise to Performance: Ecological Sanitation as A Step Towards the Elimination of Manual Scavenging in India” A report Submitted to Navsarjan Trust, Ahmedabad

Pachouri, Shubhra. November, 2008 “Discrimination and Violence Against Dalit Women Engaged in Manual Scavenging : Legal Remedies and Beyond” Masters in Development Studies Research Paper, Graduate School of Development Studies, The Hague, Netherlands

Prashad, Vijay. March 2,1996. “The Untouchable Question” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 31, No. 9, pp. 551-559

Rashtriya Garima Abhiyan. March 2012 Report on the National Public Hearing on “Rehabilitation of Manual Scavengers and their Children in India”

Srinivasan, Krithika. June 3-9,2006. “Public, Private and Voluntary Agencies in Solid Waste Management: A Study in Chennai City” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 4, No. 22, pp. 2259-2267

Thaliath, Joseph. 1961 “Notes on the Scavenger Caste of Northern Madhya Pradesh, India” Anthropos, Bd. 56, H. 5/6, pp. 789-817

Thorat, Sukhdeo and Newman, Katherine S. 2010 “Blocked By Caste: Economic Discrimination in Modern India” Oxford India Paperbacks

Thorat, Sukhdeo and Attewell, Paul. October 13, 2007 “The Legacy of Social Exclusion: A Correspondance Study of Job Discrimination in India” Economic and Political Weekly, pp. 4141-4145

Martin Macwan: Dalits; An Agenda For Social Transformation

(Accessed from: http://navsarjan.org/dalits/DALIT_social_transformation.pdf/view)

Driver, Edwin D. : Caste and Occupational Structure in Central India; Social Forces, Vol. 41, No-1, Pg-26

(+1 rating, 1 votes)

(+1 rating, 1 votes)