IJDTSA Vol.1, Issue 1 No.3 pp.18 to 34, June 2013

How deep is Caste Discrimination and Social Exclusion? Methodologies for Measuring Economic Deprivation of Dalits

Abstract

In the evolution of Indian social and economic systems, the division of labour, occupational specialisation and labour market structures have created a rigid caste structure with hierarchical specifications for occupations and earnings by birth. Though a voluminous literature discusses discrimination by caste and social exclusion of Dalits, there is a dearth of quantitative evidence on the extent of discrimination and exclusion. This paper presents the conceptual and theoretical approaches to discrimination and social exclusion and then provides methodologies to empirically measure the extent of discrimination and exclusion. Social exclusion is an act by the majority that involves multiple deprivation, relativity, agency and dynamics. The paper shows that the decomposition methodology provides the much needed quantitative evidence for the extent of the ill effects of caste system in India.

Introduction

In the evolution of Indian social and economic systems, the division of labour, occupational specialisation and labour market structures have created a rigid caste structure with hierarchical specifications for occupations and earnings by birth. Such a caste based occupational specialisation, on the one hand, has enriched the skills of workers in every occupation, and the system ensured a regular labour supply for any type of occupation, thereby maintained caste equilibrium. However, the caste based economic organisation produced strong barriers for mobility and progress and led to marginalisation, discrimination, oppression and exclusion of the poor, weaker, marginal and vulnerable sections in the caste hierarchy. The caste structure also alienated these so called lower castes from the control of economic resources and the purview of political power. Even the economic progress of an individual depends largely on the caste to which he/she belongs. Thus, the caste hierarchy in India continues to strengthen social exclusion and discrimination in almost all walks of life. Even the expectations of the lower caste workers, with equal capabilities, were lower compared to those of the upper caste workers. The lower castes were generally satisfied with their economic and social conditions within the caste hierarchy, and there was little incentive for them to change their position, Low expectations, abject poverty and illiteracy coupled with religious and social justification prevented the upward occupational mobility of the lower castes. The caste structure is evidently a labour structure, created primarily for division of labour and occupational specialisation. Whenever any group tried to disrupt the system, the other groups severely suppressed it, and the caste equilibrium was maintained.

The caste system is thus functional to the generation and maintenance of economic and social inequalities by perpetuating tied jobs and selective discrimination. The persistence of the caste system is evident, not only in the social structure but also in the Indian labour market and the educational sector. The strength of caste prejudice observed in India suggests that preference for discrimination might well have an influence in the labour market and the caste prejudice promotes the economic interests of some groups and harms those of others (Banerjee and Knight, 1985). The lower caste workers and students are not treated on par with their higher caste counterparts in many organisations and institutions. Discrimination appears to operate at least in part through the assignment of workers to occupations, with the lower caste workers (scheduled castes) disproportionately represented in poorly paid ‘dead-end’ jobs. Differential access to jobs among castes is potentially an important cause of caste differences not only in jobs but also in earnings and occupational mobility.

There is extensive literature on the economics of race and sex discrimination in the labour market (see Psacharopoulos and Tzannatos, 1991 and the references therein). Though a voluminous literature discusses discrimination by caste and social exclusion of Dalits, there is a dearth of quantitative evidence on the extent of discrimination and social exclusion. Unlike race or sex discrimination, where the identity of the individual is revealed by colour or origin, caste discrimination involves the identification problem. As job seeker’s caste may not be revealed to the employer. Under such circumstances, it may not be possible to exercise discrimination based on any objective criterion and hence caste is less likely to play an important role in determining earnings. However, it is widely observed that caste discrimination both in jobs and in earnings is a reality in India (Lakshmanasamy and Madheswaran, 1995). Apart from the observation that there are fewer persons from the lower castes in many occupations, especially in high paying and higher posts, and even in the comparable jobs lower caste persons earn less than the upper caste persons in India, the mechanisms for caste discrimination in jobs and earnings and the extent of caste discrimination are not clear and the quantitative evidence for caste discrimination is lacking.

In order to fill this gap, this paper presents the conceptual, theoretical and empirical methodologies for measuring caste discrimination. This paper first presents the conceptual and theoretical approaches to discrimination and social exclusion. The paper secondly provides the methodologies to empirically measure the extent of discrimination and exclusion. The paper shows that the decomposition methodology provides the much needed quantitative evidence for the extent of the ill effects of caste system in India.

The Concept of Discrimination

Discrimination is essentially a group concept; one group is discriminated against by other groups, on the basis of race/sex/’caste. It may manifest itself in wage/salary/earnings differentials among two groups of workers who are equally productive. It may manifest in occupational attainment/access; two individuals who are perfect substitutes may not have equal job opportunities. Job/occupational discrimination and earnings discrimination constitute ‘market discrimination’. Thus, economic discrimination refers to the unequal treatment of the equals in the market, that is, unequal pay for workers with the same economic characteristics even within the same job, or unequal pay for workers with the same economic characteristics which results from their being employed in different jobs. Also differences in average earnings may arise either because persons from disadvantaged groups may end up or crowded in low paying jobs or because the level of unemployment for such lower end castes is higher due to poor human capital or because the higher castes may possess characteristics suitable for certain jobs. Thus, the observed differentials in jobs and earnings among different castes or groups may have as components both the labour market advantages and disadvantages, apart from the pure discriminatory aspects. The main point to be noted here is that discrimination is not based on any objective criteria like productivity. If only differentials on treatment arise on productivity irrelevant aspect i.e. caste, then there is a case for caste discrimination. For example, earnings/wage differentials due to differential capabilities is not called discrimination; such differences in earnings are justifiable, at least from the point of view of the employers. Only non-justifiable difference is called discrimination.

Discrimination: Theoretical Approaches

Becker’s Taste or Preference Approach

According to the neoclassical theory of labour market discrimination, earnings differences arise among productive workers because group specific characteristics are valued in the market and the values attached to these characteristics are determined by the prejudices of the employer. For Becker (1971), who has pioneered the work on (racial) discrimination, there exists a’ preference’ or ‘taste’ for discrimination, i.e. discrimination is practiced since people have preferences concerning persons with whom they would like to have economic relations. They are prepared to incur costs for being allowed to deal with one particular category of economic agents instead of another. This readiness to pay for avoiding contact with some groups in society is expressed in terms of a discrimination coefficient, which states the extent to which one group is favoured over another. The existence of this ‘taste for discrimination’ explains the process whereby people who in some sense are equal do not receive the same treatment in economic transactions. In Becker’s (1971) words, ‘if an individual has a taste for discrimination then he must act as if he were willing to pay something either directly or in the form of reduced income, to be associated with some persons instead of others. When actual discrimination occurs he must in fact either pay or forfeit income for this privilege’.

According to Becker, white persons have a taste for discrimination against the blacks – racial discrimination. Similarly, females are discriminated against males – sex discrimination. Similarly, scheduled castes/tribes are discriminated against non-scheduled castes/tribes in India – caste discrimination. Thus, the Beckerian approach attempts to explain why persons or groups in the same type of occupations receive different wages and why groups with common economic characteristics are found in different labour markets. Empirically, after accounting for all possible differential capabilities in earnings differentials, the non-justifiable difference (residual) is termed as discrimination.

Arrow’s Statistical Discrimination Approach

Rejecting the Beckerian argument of taste/preference as the cause of discrimination, the statistical theory (Arrow, 1973; Phelps, 1977) explains discrimination as a consequence of imperfect/incomplete information. Employers have an idea about the productivity of different groups which is on the whole correct, but not about the productivity of each individual. Group affiliation thus becomes an inexpensive aid for employers when making employment decisions. All individuals of the group are judged the same and therefore paid the same amount irrespective of individual merit. According to Phelps (1977), ‘the employer who seeks to maximise expected profit will discriminate against blacks or women if he believes them to be less qualified, reliable on the average than whites or men respectively and if the costs of gaining information about individual applicants is inexpensive. Skin color or sex is taken as a proxy for relevant data not sampled. The a priori belief in the probable preferability of a white or male over a black or female candidate who is not known to differ in other respects might stem from the employer’s previous statistical experience with the two groups’.

Given that employers are averse to risk, and two groups have the same expected productivity, discrimination occurs against the one with most uncertain productivity. As long as differences exist in the ability of employers to measure individual productivity correctly (by the use of tests) and as long as the past hiring experience lends support to the employers’ decision they will continue to exercise discrimination. Thus, employers use race/sex/caste as a criterion for hiring when they believe that the imperfectly observable economic characteristics are variedly distributed between the two groups, and the average quality of a given race/sex/caste is used to predict the quality of individuals of that race/sex/caste. For example, scheduled caste workers seeking employment must accept a lower wage/job in order to offset the lower probability of their offering wage/employment. Thus, caste is a screening device used by employers for differences in productivity in the absence of perfect information.

Akerlof’s Incentives Approach

According to Akerlof (1976; 1980), economic incentives are the prime motivation for discrimination and this is achieved by creating monopoly in the form of caste codes/customs. Akerlof has shown that how social customs possess characteristics which make discrimination stable time. In a caste society, any transaction that breaks the caste custom changes the subsequent behaviour of uninvolved parties towards the custom-breaker. If a member of a higher caste relates (transacts) to a member of a lower caste (say untouchables) in a given way, then according to caste codes, the former would be out-casted and the latter would find subsequent relations (transactions) almost impossible. This drastically reduces the normal economic opportunities available to both the parties. This is so because the caste may perform the role of a cartel. Hence, it is economically profitable for the individual to follow the caste rules. When the punishment of becoming an out-caste is predicted to be sufficiently severe, the caste system is held in equilibrium, irrespective of tastes, by pure economic incentives. The arguments in the Akerlof’s utility function are profit and prestige in the society to which one belongs. Prestige crucially is dependent on following the caste code and the size of the caste population which supports it. Breaking the code may be economically profitable, but leads to lessening of prestige in the society. Depending on the population supporting the conventional code, the caste equilibrium implies that everybody follows the code or nobody does. Akerlof has argued that the fear of becoming an out-caste forces everyone to follow the code, and hence the caste system provides no economic incentives to violate the caste code. Thus, the prediction of the caste system becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy and it works spontaneously to maintain the caste equilibrium.

Besides these economic theories, there are alternative explanations for the observed earnings differentials such as labour market segmentation hypothesis, screening hypothesis, job ladder or queuing hypothesis, and sociological theories, which attempt to explain discrimination. It has often been argued that the higher caste groups receive better education and hence higher earnings, a hypothesis known as differential ability hypothesis. Getting education is often portrayed as a signal or screening or filter to the jobs and better educated high caste workers earn higher earnings or the market rewards are higher to them. The job competition or queuing theory argues that workers compete for jobs rather than wages, and those with more educational qualifications bump out from the labour queue the less qualified and get the job. The essentials of the approach are that exists at least two distinct labour markets, that workers compete within but not across each market for jobs, that workers in secondary labour markets are treated in a much inferior way to those in primary markets and that mobility barriers prevent the movements of workers between segments. The dual or segmented labour market hypothesis argues that education helps workers belonging to the ‘primary segment’ of the market (i.e. more skilled and high paying jobs), but not those in the ‘secondary segment’ of the market (i.e. less skilled and inferior jobs), and hence the observed earnings differentials (Taubman and Wachter, 1986). Still others like Bowles and Gintis (1975) attribute earnings differentials to personality traits and job attributes and the degree of socialisation in work place. As these personality traits are also rewarded positively in the labour market, there is the observed positive correlation between earnings and those who possess these traits, normally the better off sections of the population.

Even though the motivations and mechanisms of discrimination are analysed differently in different theories, all theories accept that there is discrimination and it is severe and distortionary. The elimination of discrimination may be possible in the long-run, as economic incentives and competition ensure fair wages. However, social prejudice is too strong among all groups in society, and caste discrimination continues to dominate Indian labour market.

The Concept of Social Exclusion

When an individual belonging to a particular group/caste is in a disadvantageous position in the society, then it is the case of discrimination; when the whole group/caste in the society is treated differently by the major caste groups, then it is the case of exclusion. Those who are disadvantaged or marginal to society are typically called ‘excluded’ or ‘marginalised’. When this marginalisation arises due to some ruptures in social relationships and when some sections of the society altogether are systematically neglected by the rest from the core on the basis of some historical, geographical, birth or some other irrelevant aspects the ‘social exclusion’ arises and the continued oppression or disadvantage assumes significant proportions. Social exclusion, though widely prevalent in developing countries for a long time, as a term originating in the European debate on poverty since the famous Rene Lenoir in 1974 study, has been increasingly used to analyse marginalisation in the developing world as well. The publication of Les exclus by Rene Lenoir in 1974 was a milestone in the emergence of social exclusion as a concept. He employed it to raise alarm at the inability of an expanding economy to include certain physically, mentally and socially disabled groups. In the UK, the Rowntree (1901) study, applying the ‘minimum necessaries for the maintenance of merely physical efficiency’, showed that the idea of the ‘idle poor’ as a fallacy, as the chief wage-earner was ‘in regular work, but at wages insufficient to maintain a moderate family in a state of physical efficiency’, due to deprivation.

At the social level, exclusion is related to the dissatisfaction or unease felt by people who are faced with situations in which they cannot achieve their objectives. Both the paths of stigmatisation and interaction between society and excluded populations are more fluid, more complex and less clear. The type of exclusion has by no means disappeared from the face of earth and the rise of fundamentalism, penalisation of otherness continue to be manifest, alongside with the more indirect processes of urban separation, differentiation, certain selective mechanisms of production and consumption, social stratification, stigmatisation, of the most vulnerable groups.

Understanding the concept of social exclusion cannot avoid a historical and multi-disciplinary approach as it is pervading all sections of the society and dynamic rather than in a static one. As societies are diverse and endowed with different resources and varied practices, there is no unanimity in defining social exclusion. It has been the subject of many attempts at definition, delimiting its meaning and scope from poverty, deprivation, marginalisation, new poor, to multi-dimensional and accumulated processes (Burchardt, Le Grand and Piachud, 2002; Hills, Le Grand and Piachaud, 2002).

Some of the varied definitions, rather meaning and scope, of the concept of social exclusion are

Access: “Social exclusion means being unable to access the things in life that most of society takes for granted. It the not just about having enough money, although a decent income is essential. It is a build-up of problems across several aspects of people’s lives”.

Rights: “Social exclusion means a lack of belonging, acceptance and recognition. People who are socially excluded are more economically and socially vulnerable, and hence they tend to have diminished life experiences”.

Disadvantage: “Social exclusion describes a process by which certain groups are systematically disadvantaged because they are discriminated against on the basis of their ethnicity, race, religion, sexual orientation, caste, descent, gender, age, disability, HIV status, migrant status or where they live”. Discrimination occurs in public institutions, such as the legal system or education and health services, as well as social institutions like the household.

Birth: “Social exclusion is about more than income poverty. It is a short–hand term for what can happen when people or areas have a combination of linked problems, such as unemployment, discrimination, poor skills, low incomes, poor housing, high crime and family breakdown. These problems are linked and mutually reinforcing. Social exclusion is an extreme consequence of what happens when people don’t get a fair deal throughout their lives, often because of disadvantage they face at birth, and this disadvantage can be transmitted from one generation to the next”.

Denial: The UK government’s definition of social exclusion is: “Social exclusion is a complex and multi-dimensional process. It involves the lack or denial of resources, rights, goods and services, and the inability to participate in the normal relationships and activities, available to the majority of people in a society, whether in economic, social, cultural or political arenas. It affects both the quality of life of individuals and the equity and cohesion of society as a whole”.

Marginalisation: Social exclusion is the “cumulative marginalisation: from production (employment), from consumption (income poverty), from social networks (community, family and neghhbours), from decision-making and from an adequate quality of life”.

Rupture: “Social exclusion may therefore be understood as an accumulation of confluent processes with successive ruptures arising from the heart of the economy, politics and society, which gradually distances and places persons, groups, communities and territories in a position of inferiority in relation to centres of power, resources and prevailing values”.

Distance: “Exclusion has been described as a cumulative and multi-dimensional process which, through successive ruptures, distances individuals, groups, communities, and territories from the centers of power and prevailing resources and values, gradually placing them in an inferior position”.

Activity: “An individual is socially excluded if (a) he or she is geographically resident in a society, (b) he or she cannot participate in the normal activities of citizens in that society, and (c) he or she would like to participate, but is prevented from doing so by factors beyond his or her control”. The most important five dimensions of ‘normal’ activities are: consumption, savings, production, political and social.

Four elements that recur in any discussion of social exclusion are (Atkinson, 1998): multiple deprivation, relativity, agency and dynamics. Multiple deprivation implies that social exclusion is about more than simple poverty, more about the absence of community or social interactions. There is no absolute social exclusion; relativity refers that people are excluded from a particular society in a particular place at a particular time. Since exclusion is an act, there are agents who undertake it; an act by the majority against the minority. It is dynamics as it is perpetual.

A running theme across these meanings is clear; the disadvantaged, by birth or process, has been disadvantaged or denied the rights or access to the resources to develop themselves. This accumulated neglect develops into a social issue with continuous neighbourhood and community distancing. The marginalised are those persons who are removed from the center of the society. They may distance themselves away voluntarily or may be prevented by others, individuals or institutions. Getting into the core of the society may be beyond their capacity or control. Thus, social exclusion is about the inability of the society to keep all groups and individuals within reach of what can be expected as a society. It is about the tendency to push vulnerable and difficult individuals into the least popular places, furthest away from common aspirations. It means that some people feel excluded from the mainstream, as though they do not belong.

Thus, social exclusion is the denial or disadvantage of rights or access to resources to develop for the disadvantaged or marginalised groups on the basis of caste, birth, place or process. Then, social exclusion is about the inability of the society to keep all groups and individuals within the mainstream and the tendency to push vulnerable and difficult groups or individuals into the periphery as though they do not belong to that society (Silver, 1994; Estivill, 2003). It is not difficult to identify the socially excluded groups. Some of the indicators of exclusion are: income, economic resources as a whole, living conditions. Apart from income, employment, education, housing, health, consumption durables, delinquency, access to services, justice, leisure and socio-cultural integration are commonly used in the measurement of exclusion. The main dimensions and indicators to identify socially excluded are

Measuring Discrimination and Social Exclusion: Empirical Methodologies

To measure the extent of discrimination, almost all studies heavily relied on the earnings differentials and job differences. Since earnings differentials reflect, after accounting for all possible explainable differences in characteristics, the unobservable part, it is convenient to calculate the discrimination coefficient. In the earnings differentials approach , the Blinder (1973) Oaxaca (1973) decomposition technique is the widely used methodology. It should be noted at the outset that the literature on the measures of discrimination is almost independent of theoretical literature; it is not directly derived from the theoretical models. Also, the measures of discrimination are not direct measures; they are residuals. The discrimination coefficient, measured by using the earnings differentials approach, provides an estimate of the prevalence of caste discrimination in the labour market. It is to be noted that the decomposition technique for earnings differentials is based on average earnings of the two groups, the same approach can be equally applied to measure the extent of social exclusion as social exclusion refers to the discrimination against the group as a whole.

Wage/Earnings Differentials Approach

The analysis of earnings determinants is based on the human capital framework developed by Mincer (1974). The human capital earnings function, which determines the market rewards (wages/earnings) W can be written in logarithmic form as

lnW = Xβ + ε

where X is the matrix of observed wage determining human capital variables, β is a vector of returns to these variables, and ε is the error term. There are two different approaches to the study of earnings differentials between two groups (castes). First, one can examine whether there is a fixed premium/disadvantage associated with the caste of the worker. This relates to a ‘shift’ in the earnings function. It consists of running a regression of earnings upon the characteristics of all workers including a separate variable which indicates the caste of the worker, that is

lnW = α + Xβ + γC + ε

where C is a dummy variable taking the value of 1 if the worker belongs to the discriminated against caste and 0 if the worker belongs to non-discriminated caste. The coefficient reveals whether discriminated workers receive on an average lower wage than the other caste workers (γ<0), other things being equal. However, this approach constraints the values of the coefficients on other explanatory variables (Xs) to be the same across caste groups, therefore it is bound to yield biased estimates. Moreover, it is not possible to estimate the extent of job discrimination.

The second approach is the popular decomposition technique. This approach can be used to investigate whether the individual characteristics of different workers are rewarded differently in the labour market. This approach relates to a difference in the ‘slope’ coefficients of the earnings functions. This method requires two earnings regressions separately on workers from two different groups and both the regressions should have a strictly comparable specification. By subtracting the two earnings equations it is possible to determine what percent of the earnings difference is due to the different endowment levels (endowment or explained component) of the two groups and what is due to the way in which each group’s endowments are valued in the market place (coefficients or unexplained component). The latter is derived as a residual and is termed as ‘discrimination’. This decomposition method was first developed by Blinder (1973) and Oaxaca (1973) and later extended Reimers (1983; 1985) and to address the index number problem by Cotton (1988). The decomposition analysis is based on observed mean characteristics, and the regression coefficients indicate the way in which the labour market rewards the background attributes.

Decomposition of Differential Incomes

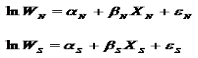

Let the separate earnings regressions for two groups be

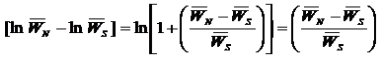

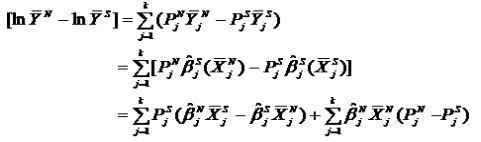

where the subscripts N and S represent the non-discriminated and discriminated workers respectively. The difference in the average logarithms of earnings (![]() ) can be shown to be equal to the percentage differences in the average earnings (

) can be shown to be equal to the percentage differences in the average earnings (![]() )

)

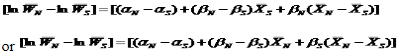

Rewriting the right hand side of the above equation, we have

![]()

Adding to and subtracting from this equation the term (![]() ) and rearranging produces the following two decompositions of gross differentials in average earnings

) and rearranging produces the following two decompositions of gross differentials in average earnings

That is G = D + E

Thus, the gross difference in mean earnings between the two group workers is due to two different sources – first, the differential rewards to personal characteristics of disadvantaged and the advantaged groups in the labour market including the difference between the constant terms and second, the difference in the quantities of these characteristics held by the weaker and the dominant group workers. The portion of earning gap due to differences in endowments of productive characteristics can be considered to be non-discriminatory (or ‘justified’). On the other hand, the portion of earnings gap due to differences in the values of coefficients, including the constant term can be regarded as the upper bound of (‘unjustified’) discrimination.

In the empirical analysis, generally the favoured group (N) wage structure has been taken as the standard for comparison with the disfavoured group (S) wage structure to calculate the discrimination coefficient. This raises the index number problem: which wage structure is non-discriminatory. There may also be favoured groups (nepotism) and hence overpayment to that group and underpayment to the disfavoured. The labour market may also have both nepotism and discrimination. To overcome this identification problem, Neumark (1988) suggests that the non-discriminatory wage structure can be derived from an earnings function estimated over the pooled sample of all caste groups and Cotton (1988) suggests a non-discriminatory wage structure by weighting the wage structures of the two groups by their respective proportions in the population.

In the approach suggested by Cotton (1988) using the non-discriminatory wage structure, the discrimination component of earnings differentials comprise two parts – one due to the over payment to the favoured group and the other representing under-payment to the disfavoured group. The resulting Cotton decomposition is

![]()

where β* is the wage structure that would prevail in the absence of discrimination. The non-discriminatory wage structure β* is obtained by weighting the caste group wage structures by the respective proportions of each caste in the labour force, as given by

![]()

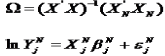

The Neumark (1988) and Oaxaca and Ransom (1994) non-discriminatory wage structure is obtained as

![]()

where Ω is a weighting matrix of the form

![]()

where X is the matrix of pooled sample characteristics and X N of favoured group characteristics. The formulation of discrimination takes no account on differences in occupation. If the same characteristics that determine wages also determine occupation then this approach would be sufficient. However, there are other determinants of occupational attainments, some from personal characteristics and some from discriminatory constraints on occupational choice or entry or attainment. Indeed, persons with similar characteristics but who have attained different occupations often earns differing wages implying that additional factors also influence occupation. Most studies deal with this by including dummy variables for occupation in the earnings regression implicitly treating all differences between the occupational distributions of caste groups as justified and ignoring the potential discriminatory nature of these differences. The Brown et al. (1980) method explicitly incorporates a separate model of occupational attainment of caste groups into the analysis of wage differentials.

Following this approach, the mean wage differentials between caste groups can be decomposed into explained and unexplained intra- and inter-occupational differences. Let the occupation specific earnings functions for discriminated and advantaged castes be

where j denotes occupations and ε is the error term. The choice of occupation can influence the wage a worker receives either because occupational wages are influenced by institutional factors or because they represent human capital acquired in the job. Where this is the case, a distinction can be made between wage/earnings discrimination (WD) and job discrimination (JD). If the proportions of discriminated and non-discriminated workers in each occupational sector is denoted by P N and P F respectively, then the overall mean wage differentials between caste groups may be calculated from as

That is, (WG) = (WD) + (JD)

where WD represents that part of the gross difference in wages (WG) which is due to wage differences within occupation and JD represents that part which is due to differences in occupational composition.

Let be the proportion of discriminated caste workers in the sample who would be in occupation j if they faced the same occupational structure as non-discriminated, then WG can be further decomposed as

![]()

(WG) = (WE) + (WD) + (JE) + (JD)

where WE is the part of earnings differential explained by differences in personal characteristics since both the wage structure and the job proportions are being held constant; WD represents wage discrimination since it isolates the effect of caste/group differences in the wage structure within occupations; JE is the explained part of differences in occupational attainment due to differences in endowments; and JD is the job discrimination since it isolates the effect of sex differences in occupational attainment which cannot be explained by group differences in endowments. Thus, the two components, WD and JD, put together constitute the extent of caste discrimination in the labour market.

Though the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition technique in its varied forms are extensively used to study the earnings differentials across race, gender, caste, sector and occupation, the methodology may not explain whether such earnings differentials have narrowed or widened over time and space. In order to study the sources of changing wage differentials, exact information on the position of each individual in the distribution of the wages across different groups are needed. This is achieved by specifying the residual gap further in terms of standard deviation of the residuals and the standardised residuals. The decomposition methodology proposed by Juhn, Murphy and Pierce (1993) identifies the sources of the changing wage gap (inequality) and their effects on narrowing or widening of the wage gap over a period of time, and the application of this technique has been demonstrated by Blau and Khan (1994; 1996; 1997). Assuming that the returns to individual characteristics are the same for both caste groups (i.e. β N=β S), Juhn, Murphy and Pierce (1993) construct an auxiliary wage equation for group S as

![]()

and apply the decomposition

![]()

where σ N is the standard deviation of the residual ε N and . The first and the second terms are the predicted gap and the residual gap in earnings respectively.

Another weakness of the decomposition technique is that it decomposes only the average/mean wage/earnings differentials as it is based on the ordinary least squares method for estimating wage equations. As is well known such estimation and decomposition methodology applied to mean wage gap suppresses individual heterogeneity and one may not know the earnings differentials at different points of the earnings distribution. The quantile regression technique provides for the measurement of degree to which the earnings gap may vary at different points in the conditional earnings distribution (Koenker and Bassett, 1978; Buchinsky, 1994; 1998; Koenker, 2005; Nopo, 2008; Firpo, Fortin and Lemieux, 2009), and the application of this method has been demonstrated by Garcia, Hernandez and Lopez-Nicolas (2001), Machado and Mata (2005), Gardeazabal and Ugidos (2005) and Melly, 2005a; 2005b).

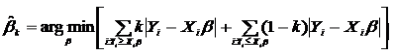

In the regression models of decomposition, β is normally the unconditional mean effect of increasing the mean value of X (background or human capital characteristics) on the (unconditional) mean value of Y (the wages/earnings). But, under conditional on the wage distribution, the β indicates the effect of X on the conditional mean E(Y│X) in the modal E(Y│X) = Xβ. The quantile regression allows to study the effects of a covariate on the whole conditional distribution of the dependent variable. For the wage distribution, a quantile regression model for the k th conditional quantile

![]()

can be solved for the following minimisation problem

In comparison to the Oaxaca and Blinder decomposition, the quantile regression method decomposes the quantiles of the wage distribution as (Melly, 2005a)

![]()

where the first term is the contribution of coefficients and the second term is the contribution of the covariates to the difference between the k th quantile wage distributions between the castes/groups. Equivalently, Gardeazabel and Ugidos (2003) shows it as

![]()

There is also a potential econometric problem associated with the comparison of the ant two groups, as the group characteristics may be fundamentally different. That is, the samples may not be exactly comparable as the differences in the supports of the empirical distributions of individual characteristics of the two groups mat lead to misspecification of the earnings distributions. What needs to be assessed is the earnings that would have been accrued to the discriminated caste group had there been not discrimination at all. That is, earnings comparison should be between the actual earnings (with discrimination) and the potential earnings (without discrimination). However, the same sample is not observed in both the states. Hence, one need to construct a counterfactual in order to know what could be the earnings for this sample without discrimination. This is akin to the outcomes in the programme/impact evaluation analysis where the impact of some treatment on some outcome is evaluated (Imbens and Wooldridge, 2009; Gertler et al. 2011).

As discrimination is the result of treatment by some caste/group against the other caste/group persons, let D=1 denote treatment (discrimination in wages/earnings) for the discriminated caste/group (Dalits) and D=0 for the untreated (no discrimination) comparable caste/group. Let Y 0 denote the potential outcome (wages/earnings) in the untreated (no disctimination) state and Y 1 the potential outcome (wages/earnings) in the treated (discrimination) state. Each person is associated with a (Y 0,Y 1) pair that represents the outcomes that would be realised in the two states of the world. Because a person can only be in one state at a time, at most one of the two potential outcomes is observed at any point in time. Therefore, the observed outcome can be written as

![]()

Therefore, discrimination is the difference from moving an individual belonging to the discriminated against caste/group from that state (treatment) to the state without discrimination, i.e.

![]()

Because only one of the states is observed, the extent of discrimination from the treatment is not directly observed for anyone. Inferring discrimination from treatment therefore requires solving a missing data problem. The impact/programme evaluation literature has developed a variety of different approaches to solve this problem. The common solutions to construct the counterfactuals (missing data) are randomised experiments (Rubin, 1973), propensity to score (Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1983), matching (Rosenbaum, 1989), difference-in-differences (Ashenfelter and Card, 1985), regression discontinuity design (Van der Klaauw, 2008), and smoothing methods (Heckman, Ichimura and Todd, 1997) and their applicability has been demonstrated by Heckman, Ichimura and Todd (1999). The basic clue is to uncover some features of the discrimination (treatment) impact distribution, such as the mean or median discrimination impact. The issue is then to estimate the following two key parameters of interest (Heckman and Robb, 1985; Heckman, Lalonde and Smith, 1999).

The average wages/earnings with discriminating wage structure (treatment) for persons with characteristics X, the average impact of treatment (ATE), given by

![]()

The average wages/earnings with discriminating earnings structure (treatment) for discriminated persons with characteristics X, the average impact of treatment on the treated (TT), given by

![]()

The ATE parameter is the average wage/earnings under discrimination that would be experienced on average if a randomly chosen person with characteristics X were assigned to the Dalit caste/group. The TT parameter is the average wage/earnings for individuals who actually belong to the Dalit caste/group (for whom D=1). If individuals in the labour market tend to be ones who face discrimination, then we would expect TT(X) < ATE(X).

Conclusion

In the evolution of Indian social and economic systems, the division of labour, occupational specialisation and labour market structures have created a rigid caste structure with hierarchical specifications for occupations and earnings by birth. Such caste system has enriched the skills of workers in every occupation, and the system ensured a regular labour supply for any type of occupation, thereby maintained the caste equilibrium. Unfortunately, the caste based economic organisation produced strong barriers for mobility and progress and led to marginalisation, discrimination, oppression and exclusion of the poor, weaker, marginal and vulnerable sections in the caste hierarchy. The practice of caste hierarchy in India has alienated both the individual belonging to the lower castes (caste discrimination) and the whole caste (social exclusion) from the mainstream and prevented their access to productive resources and upward mobility. The caste system is thus functional to the generation and maintenance of economic and social inequalities by perpetuating tied jobs, selective discrimination, and social exclusion.

As both discrimination and social exclusion are reflected in the labour markets, both in occupational attainment and earnings, this paper has shown that the extent of discrimination and social exclusion can be measured by comparing the job attainment and wages/earnings of different castes/social groups. However, all earnings differentials are not due to either discrimination or exclusion; differences in earnings among castes may also be due to the individual characteristic differences. Towards this issue of identifying discrimination and social exclusion, this paper has first presented the conceptual and theoretical approaches on discrimination and social exclusion. The economic theories of discrimination and exclusion are based on taste or preference or imperfect information, or lack of incentives. Taking both as group based concepts, this paper has secondly provided the decomposition methodologies to empirically measure the extent of discrimination and social exclusion. The earnings differentials by caste/groups approaches decompose the observed differences in occupational attainment and earnings between castes into differentials that could be explained by observed differences in characteristics which can be justified, and that could not be explained by any market relevant characteristics which cannot be justified. Hence, the latter part of earnings differentials is regarded as a measure of discrimination and exclusion. The paper has shown that the decomposition methodology provides the much needed quantitative evidence for the extent of the ill effects of caste system in India.

References

Atkinson, A.B. (1998) “Social Exclusion, Poverty and Unemployment”, in A.B. Atkinson and J. Hills (eds.): Exclusion, Employment and Opportunity, CASEpaper 4, London: Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics.

Akerlof, G.A. (1976) “The Economics of Caste and of the Rat Race and Other Woeful Tales”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 90, 599-617.

Akerlof, G.A. (l980) “A Theory of Social Custom, of which Unemployment may be One Consequence”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 94, 749-775

Arrow, K.J. (1973) “The Theory of Discrimination”, in O. Ashenfelter and A. Rees (eds.): Discrimination in the Labor Market, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 3-33.

Ashenfelter, O. and D. Card (1985) “Using the Longitudinal Structure of Earnings to Estimate the Effects of Training Programs”, Review of economics and Statistics, 67, 648-660.

Banerjee, B. and J.B. Knight (1985) “Caste Discrimination in the Indian Urban Labour Market”, Journal of Development Economics, l7, 277-307.

Becker, G.S. (1971) The Economics of Discrimination, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Birdsall, N. and R.H. Sabot (1991) Unfair Advantage: Labour Market discrimination in Developing Countries, The World Bank.

Blau, F.D. and L.M. Khan (1994) “Rising Wage Inequality and the US Gender Gap”, American Economic Review, 84, 23-28.

Blau, F.D. and L.M. Khan (1996) “The Gender Earnings Gap: Some International Evidence”, Economica, 63, 29-62.

Blau, F. D. and L. M. Kahn (1997) “Swimming Upstream: Trends in the Gender Wage Differential in the 1980s”, Journal of Labor Economics, 15, 1-42.

Blinder, A. (1973) “Wage Discrimination: Reduced Form and Structural Estimates”, Journal of Human Resources, 8, 436-455.

Bowles, S. and H. Gintis (1975) Schooling in Capitalist America, New York: Basic Books.

Brown, R.S., M. Moon and S. Zoloth (l980) “Incorporating Occupational Attainment in Studies of Male-Female Earnings Differentials”, Journal of Human Resources, 15, 3-28.

Burchardt, T., J. Le Grand and D. Piachaud (2002) “Degrees of Exclusion: Developing a Dynamic Multi-dimensional Measure”, in J. Hills, J. Le Grand and D. Piachaud (eds.): Understanding Social Exclusion, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Buchinsky, M. (1994) “Changes in US Wage Structure 1963-1987: An Application of Quantile Regression”, Econometrica, 62, 405-458.

Buchinsky, M. (1998) “Recent Advances in Quantile Regression Models”, Journal of Human Resources, 33, 88-126.

Cappo, D. (2002) “Social Inclusion Initiative: Social Inclusion, Participation and Empowerment”, Address to Australian Council of Social Services National Congress, November 28-29, 2002, Hobart.

Cotton, J. (1988) “On the Decomposition of Wage Differentials”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 70, 236-243.

Estivill, J. (2003) Concepts and Strategies for Combating Social Exclusion: An Overview, Geneva: International Labour Organisation.

Firpo, S., N.M. Fortin and T. Lemieux (2009) “Unconditional Quantile Regressions”, Econometrica, 77, 953-973.

Garcia, J., P.H. Hernandez and A. Lopez-Nicolas (2001) “How Wide is the Gap? An Investigation of Gender Wage differences Using Quantile Regression”, Empirical Economics, 26, 149-167.

Gardeazabal, J. and A. Ugidos (2005) “Gender Wage Discrimination at Quantiles”, Journal of Population Economics, 18, 165-179.

Gertler, P.J., S. Martinez, P. Premand, L.B. Rawlings and C.M.J. Vermeersch (2011) Impact Evaluation in Practice, Washington D.C.: World Bank.

Heckman, J. and R. Robb (1985) “Alternative Methods for Evaluating the Impact of Interventions”, in J. Heckman and B. Singer (eds.): Longitudinal Analysis of Labor Market Data, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University, 156-246.

Heckman, J. J., H. Ichimura, and P. Todd (1997) “Matching as an Econometric Evaluation Estimator: Evidence from Evaluating a Job Training Program”, Review of Economic Studies, 64, 605-664.

Heckman, J. J., H. Ichimura, and P. Todd (1998) “Matching as an Econometric Evaluation Estimator”, Review of Economic Studies, 65, 261-294.

Heckman, J., R. Lalonde and J. Smith (1999) “The Economics and Econometrics of Active Labor Market Programs”, in O. Ashenfelter and D. Card (eds.): Handbook of Labor Economics, Volume 3A, Amsterdam: Elsevier North-Holland, 1865- 2097.

Hills, J., J. Le Grand and D. Piachaud (eds.): Understanding Social Exclusion, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Imbens, G.W. and J.M. Wooldridge (2009) “Recent Developments in the Econometrics of Program Development”, Journal of Economic Literature, 47, 5-86.

Juhn, C., K. M. Murphy, and B. Pierce (1993) “Wage Inequality and the Rise in Returns to Skill”, Journal of Political Economy, 101, 410-442.

Koenker, R. (2005) Quantile Regression, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Koenker, R. and G. Bassett (1978) “Regression Quantiles”, Econometrica, 46, 33-50.

Lakshmanasamy, T. and S. Madheswaran (1995) “Discrimination by Community: Evidence from Indian Scientific and Technical Labour Market”, Indian Journal of Social Science, 8, 59-77.

Lenoir, R. (19740 Les Exclus: Un Francais Sur Dix, Paris: Editions du Seuil.

Lloyd, C., T. Samson and F.P. Deane (2006) “Community Participation and Social Inclusion: How Practitioners Can Make a Difference”, Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health , 5, 3, 1-10.

Lundahl, M. and E. Wadensjo (1984) Unequal Treatment: A Study in the Neo-classical Theory of Discrimination, London: Croom Helm.

Machado, J. F. and J. Mata (2005) “Counterfactual Decomposition of Changes in Wage Distributions using Quantile Regression”, Journal of Applied Econometrics, 20, 445-465.

Melly, B. (2005a) “Public-Private Sector Wage Differentials in Germany: Evidence from Quantile Regression”, Empirical Economics, 30, 505-520.

Melly, B. (2005b) “Decomposition of Differences in Distribution Using Quantile Regression”, Labour Economics, 12, 577-590.

Mincer, J. (1974) Schooling, Experience and Earnings, New York: Columbia University Press.

Nalla Gounden, A.M. (199l) “Labour Market Discrimination”, in V.N. Kothari (ed.): Issues in Human Capital Theory and Human Resource Development Policy, Bombay: Himalaya Publishing Company.

Neumark, D. (1988) “Employer’s Discriminatory Behaviour and the Estimation of Wage Discrimination”, Journal of Human Resources, 23, 279-295.

Nopo, H. (2008) “Matching as a Tool to Decompose Wage Gaps”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 90, 290-299.

Oaxaca, R. (1973) “Male-Female Wage Differentials in Urban Labor Markets”, International Economic Review, 14, 693-709.

Oaxaca, R. and M.R. Ransom (1994) “On Discrimination and the Decomposition of Wage Differentials”, Journal of econometrics, 61, 5-21.

Phelps, B. (1977) The Inequality of Pay, Oxford; Oxford University Press.

Psacharopoulos, G. and Z. Tzannatos (199l) (eds.) Women’s Employment and Pay in Latin America, Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

Psacharopoulos, G. and Z. Tzannatos (1992) Latin American Women’s Earnings and Participation in the Labor Force, Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

Reimers, C.W. (1983) “Labor Market Discrimination Against Hispanic and Black Men”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 65, 570-579.

Reimers, C.W. (1985) “A Comparative Analysis of the Wages of Hispanics, Blacks and Non-Hispanic Whites”, in G.J. Borjas and M. Tienda (eds.): Hispanics in the U.S. Economy, New York: Academic Press, 27-75.

Reilly, B. (1991) “Occupational Segregation and Selectivity Bias in Occupational Wage Equations: An Empirical Analysis Using Irish Data”, Applied Economics, 23, 1-7.

Rosenbaum, P. (1989) “Optimal Matching in Observational Studies”, Journal of the Anerican Statistical Association, 84, 1024-1032.

Rosenbaum, P. and D. Rubin (1983) “The Central Role of the Propensity to Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects”, Biometrika, 70, 41-55.

Rowntree, B.S. (1901) Poverty: A Study of Town Life, London: Macmillan.

Rubin, D. (1973) “Matching to Remove Bias in Observational Studies, Biometrics, 29, 159-183.

Silver, H. (1994) “Social Exclusion and Social Solidarity: Three Paradigms”, International Labour Review, 133, 5-6, 531-578.

Social Exclusion Unit (2001) Preventing social Exclusion, London: HMSO.

Taubman, P. and M.L. Wachter (1986) “Segmented Labour Markets”, in O.Ashenfelter and R. Layard (eds.): Handbook of Labour Economics, Volume 2, Amsterdam: North-Holland Elsevier, 1183-1217.

Townsend, E. (1997) “Inclusiveness: A Community Dimension of Spirituality”, Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64, 146-155.

Van der Klaauw, W. (2008) “Regression discontinuity Analysis: A Survey of Recent developments in economics”, Labour, 22, 219-245.

Walsh, J. and S. Craig (1998) Local Partnership for Social Inclusion, Dublin: Oak Press.

Woolcock, M. (2001) “The Place of Social Capital in Understanding Social and Economic Outcomes.” Isuma, 2, 11-17.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)