IJDTSW Vol.4, Issue 1 No.3 pp.36 to 48, January 2017

Higher Education and Dalit Women’s Identities Experiences, Struggles and Negotiations

Abstract

Based on the primary data, the article tries to underscore the nuances of the caste, class, gender, race, religion and region based discriminations faced by dalit women students. Though the liberal urban environment has given them spaces to negotiate their challenges, they are still caught in the shades of caste and patriarchy.

Introduction

Every society in India is divided on the basis of the caste, class, religion, ethnicity and region. Due to these divisions, Indian societies characterises with the presence of inequality, marginalisation, oppression, subjugation, exclusion and exploitation. The basis of this hierarchy in the society is the age old hegemonic caste system originated from the Hindu social order. This hierarchy is imposed on the dalits(1) right from his/her birth as an ascribed status. Since decades (still continued to), this unequal and discriminatory social stratification has denied socio-economic, political and cultural rights to dalits. As a result of this historical exclusion based on caste, the dalits have been pushed towards marginality, obstructing their means to upward mobility.

The caste system is not only the longest slavery system in the world but also the most exploitative structure in which humans are treated as polluted and lower than animals. In addition to this, the strict adherence to endogamy, stigma of untouchabililty, the notion of purity and pollution keep them aloof from the basic human rights which Indian constitution guarantees. It continues to deny equal opportunities to the dalits which comprises majority of the Hindu population.

In the process, dalit women remains the worst affected as she has to experience multifaceted discrimination, subjugation and exclusion.This trap again gets deeply entangled with the patriarchal power relations including external and internal factors(2) (Guru 1995) which have always given dalit women the lowest position. Hence, some argues that dalit woman is ‘triply jeopardise’ in terms of their gender, caste and discreet patriarchy form her own community.

In the 19 th century, Jyotiba Phule and Savitribai Phule(3) laid the foundation of women’s education along with the lower caste masses in Maharashtra. Jyotiba Phule realised education as ‘Tritiya Ratna’ or the ‘critical consciousness or the knowledge as the most important device to dismantle the brahmanical power structures (Paik, 2007). Savitribai Phule expressed in her poem ‘Go, Get Education’, that one can achieve self-reliance, wisdom and can break the shackles of caste, patriarchy, tradition and bondage through education (B. Mani & P. Sarda, 1988, c.f. Pandey 2015).

In the 20 th century, Dr.B R Ambedkar(4) revisited and extended the Phule’s vision. He viewed education as most important tool in liberating Dalits from the shackles of the oppressive Hindu Caste structure and formation of new (equal) social order. The fundamental agenda was to provide secular education, equality, human rights, dignity, inclusive and egalitarian citizenship through education (Paik 2014). But all this gets bleak when we enter into any Indian higher educational institutions.

Even in the 21 st century, the apartheid like caste system continues to spread its venom in the lives of the dalits. It is designed and formulated in such a way that it oppresses them in every field, and leave them with no choice but to obey them. Dalit women’s lowest position amongst the low, systematically denies them choices and freedoms in all spheres of life. With this backdrop, the enquiry into the spaces of education in the Indian context is necessary which transcends conventional forms of discrimination and exclusion.

Is Education For Emancipation?

In India, education is perceived as an instrument for the social and human development. It is expected to extend equal opportunities to broaden the knowledge horizon, build up capabilities, develop rationality and consciously construct alternative ways and means for emancipation and social transformation. However, an argument from the marginalized section- Dalits voices that education is used as an apparatus for reproducing destructive social stratification and for maintaining the hegemony (caste, gender, class, culture based) of the dominant sections. For them, knowledge as power for attaining democracy based on liberty, equality and fraternity is a myth. Educational institutions are seen as a microcosm of the Hinduised and male chauvinistic society.

Most of dalits receive their inspiration for education from Dr. B. R. Ambedkar. He emphasized on higher education as a chief weapon for dismantling the deeply embedded structures of power and privilege based on caste. He aimed to de-segregate higher education for the dalits through these institutions. Considering constrained accessibility for entry into educational institutions for dalits, he registered People’s Education society (PES) under which he started Siddhartha College of Arts, Science and College which is located at Fort(5). Being the first college under PES, it was designed to aim at ‘promoting intellectual, moral and social democracy’ (Rao 2014), along with earn and learn provision.

With the call of Dr. B. R Ambedkar, many untouchables came to cities to re-define their identities and contest the oppressions of history. Chairez-Garza (2014 c.f. Zelliot 2004; Gooptu 2001) argues that in the late 19 th century, as a result, urban spaces provided a space for the untouchables to pursue different occupations which marked a change in their traditional mode of occupations. Over the years, their social, educational and economic status began to improve. Dalit women also became part of this but continue to face subjugation within and outside the family structures which is often reinforced by newer forms of discrimination with its changed manifestations.

Over the last few decades, there seems to be an improvement in the enrollment in higher education among dalits students due to the constitutional safeguards and implementation of the affirmative action policies, increase in higher educational institutions resulting in rising aspirations. Wankhede (2013) in his study has mentioned that 11 per cent of students from scheduled caste reach the level of higher education compared to their population of 15 per cent (of the total population of India). But merely 2 per cent complete their courses (ibid.). The participation of dalit women in education declines progressively at successive levels of higher education.

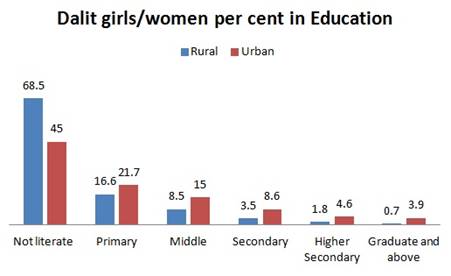

Source: Dalit women rights and citizenship in India (2010). The data belongs to 2006.

In the above figure, while looking at the urban and rural divide, the difference is fairly stark after middle school. A majority of girl students terminate their education during or before middle school. Ameager 0.7 per cent from rural area and 3.9 per cent from urban area reaches the level of graduate and above. The decline in the women’s enrollment in higher education can be attributed to the non-conducive environment (both public and private realms) to impart knowledge and enhance their socio-economic wellbeing (ibid).

The cultural practices, behaviour patterns, sex role expectations and association of women with the private domain continue to affect access to higher education (Chanana 2000). Paik (2009) goes further and states that ‘Dalit girls are subjected to the discipline, control, regulation and surveillance of not only state services in the education system but also of their parents.’Even after migrating to cities, they are still trapped in the manacle of their social identity i.e. caste.

After 1990s, dalit women started asserting differently with Dr. B. R Ambedkar’s proclamation for right to self – representation. The main objective was to make the unheard voices heard, without getting represented by the upper caste academicians, feminists sitting on privileged positions without any caste consciousness. Their experiences, struggles, negotiations, literary work started becoming literature, bringing in limelight the true picture of the women in India. They started challenging the dominant discourses in order to carve out space and status for themselves in both public and private domains. They started asserting their identities ‘with a difference.’

Struggling identities and locating self:

Tambe (2012) articulates ‘owing to the heterogeneous nature of the groups, identity of dalits is fluctuating since the beginning of their struggle.’ Dr. B R Ambedkar’s conversion to Buddhism (1956) has succeeded to a great extent in providing a new respectable identity from just being Hindu slaves. In 1972, with the Dalit panther movement, the term dalit got a new connotation. Indian academicians, writers started using the terms interchangeably like scheduled caste, ex-untouchables, Bahujans depending upon the specific socio-economic and ideological contexts as well as the politics of those who coin and use these categories (Guru 2005).

The participants have shared that the term Buddhist is more liberatory and less stigmatised, and the terms Dalit and Mahar are derogatory. In the questionnaire of this research, majority of them disclosed that they are Buddhist in religion. Though they have mentioned themselves as Buddhists, their social identity as dalits remained unchanged. Gail Omvedt (1998) notes the same argument that the Buddhist conversion ‘… allowed for a tremendous change in the consciousness of ex-untouchables but it did not produce much of a change in their social identity. Almost no caste Hindus followed them in converting, and the result was that Buddhism itself became rather “untouchable” in India.’

Stigma of the untouchability and the oppressive historical past puts dalits in the dilemma which is difficult to solve. Especially for the urban middle class educated dalits, revealing caste identities involves humiliation (ibid.) Since it is socially regressive, derogatory and undesirable term, which connotes carrying unnecessary burden of the past (Guru 2005). At the same time, for some disclosing their identity is a celebration, a device of emancipation and assertion. All these aspects also become part and parcel of the dalit women students.

It was a notion (even among dalits) that cities of India are somewhat democratic, liberatory and caste free. Guru and Sarukkai (2014) did a sociological experiment in Karnataka on a topic called ‘Publicly Talking about Caste’. In that they argue that it is not only people but also institutions have caste. Even Siddhartha College is predominantly known as ‘Dalit College’ or ‘Ambedkar’s college.’ The students are looked down upon due to their caste identities. Likewise, at times, dalit women students are labelled as cheap, characterless or very forward, Scholars (sarcasm). It was found that dalit women students hide their identity once they reach the CST (Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus) station from their home. They are inclined to do certain actions such as using altered trendy dresses, using replica-branded mobile phones, using social networking sites such as Whatsapp, Facebook, use more English words, and try to disguise their identities for being a student of Siddhartha College in order to avoid discrimination and humiliation. Here, this practice reveals that the identity overlaps at multiple levels.

Discriminations and Dalit Women

It is often assumed that caste differences do not exist among young children of this country and that educational institutions are neutral spaces. However, these premises got shattered while looking at the experiences of the participants. They asserted that school is a place of inequity and unfairness and it had left bitter experiences in their lives.

From the very young age, even when they were unaware of what caste was, they experienced caste bruises in their lives, which they recognize later. They shared that, in schools, they were beaten up, being punished for silly reasons, given less marks, abusing and passing castiest comments in front of the class, ridiculed for being poor and a low caste, asking about the parts of the body how it looks like (since dalits used to eat the flesh of the dead animals and so they that shapes and sizes of the body parts) along with the gender stereotypes.

Experiences inside college ; Being a college of Dr. B R Ambedkar, I went with the assumption that there will not be any kind of caste and class based discriminations inside the college. This assumption was crumbled after listening to the narratives of the participants. Even the dalit teachers shared their experiences of caste based discriminations. They shared that some of the upper caste teachers tries to give such examples and explanations of the text propagating the principals and thoughts of Hinduism so that their dominance continues to prevail. Greeting Jai bhim (victory to Ambedkar) becomes problem for some of the teachers.

Among the students, there are friends groups on the basis of the caste identities maintaining their social status in the society. I observed that the students with dark coloured skin were excluded from every sphere of their socialisation inside the college. Others stayed away from them, avoiding chatting, eating lunch and even sitting next to them. The politics around beauty eliminated them from all social groups including their own caste and class groups. One of the participants, Monica shared that she was discriminated because of her caste and skin colour. It is not only by the outsiders but also people within her own community discriminate her.

The interviewed participants show the similar picture where the Maratha (Other Backward classes) women students who enjoy a better social position as compared to dalits in the caste system. These students always have separate friends circle, abuse dalit girls with their caste identities, eating habits. Also, they get support from the administration for the non-academic work. Some of the students were not aware that they were discriminated on the basis of gender. They were conscious about the position of the men in society but their socialisation prevented them to question their appropriateness. Although they reach the level of men in many spheres of their lives, girls continue to be considered subordinate and inferior to men.

Experiences from workplace ; Dalit women suffer from the multiple oppressions entangled with caste, class, gender, religion, culture at all levels. It comes not only from the men and women of the upper castes and classes, but also from the men of their own castes and classes. Given the existing structural nature of discrimination, the advent of globalisation and privatisation has raised the oppressions against dalit women. It has not only dismantled the limited protection granted from the state to the dalits but also have risen an urban consciousness in the urban middle class dalits, detaching them from the dalit movement. Simultaneously, the remaining among dalits fall prey to negative effects of Liberalisation, Privatisation and Globalisation (LPG), which threatened their very existence (Kamble 2002, c.f. Tambe 2012).

Though globalisation has increased employment opportunities for the dalit women, the economic and social mobility remained an unresolved question. While caste is not discussed open in private sectors, it does not mean it is absent. Rachel Kurian (2014) talks about the interviews of the dalit women working in private sector. Dalit women have expressed their fears of getting disclose of their castes which might lead to social ostracism and even untouchability at workplace. Some of the participants have mentioned of being discriminated on the basis of their skin colour, food habits (non-vegetarianism), make up, dressing style, etc.

The issues that they face in the job site are possibly much worse than the other spheres of their daily existence. Though the dalit women students are getting jobs easily, the jobs continue to be restricted with their social identity – largely the lowest in offices and so on. On one hand, they are happy with those jobs since comparatively they are finding themselves in a better position among the others in their previous generations. On the other, they are considered as easy targets for the male chauvinists. These dalit women students face discrimination on the lines of caste, gender, and work type. For example, those who are working in places like shopping malls, McDonalds, KFCs, and CCDs, are finding themselves in a better position compared to those who are working as sales girls, typists and receptionists. It is interesting to observe that the jobs (with sophisticated names) these students are getting portrays their caste identities. Some participants have faced sexual harassment at workplace. Dalit women students of science and commerce streams were generally seen to have better command of language as compared to the arts stream students. This skill makes them fetch better paying part time jobs.

Experiences inside family ; Apart from the outside world, participants also faced gender discrimination within their own families. In some of their families sons had better position in education and access to resources than the daughters. This is in keeping with the argument by Mukhopadhyay and Seymour (1994) that ‘sons are…structurally and economically more central than daughters to family wellbeing.’ It is because boys are perceived as the core of the family, money would be spent on sons’ education like for tuitions, travelling, books, etc., as compared to daughters. When the economic resources are scarce, there are chances that son’s education is given priority over to daughter’s education.

Negotiating the Intricacies

In any negotiations, the dalit women students get little and sacrifices major portion of its interest to the dominant section. The stories of their negotiations are mostly painful. The negotiation helps them somewhat to make the insufferable endurable. They find covert ways to manage the existing hegemonic system and it includes means such as pacts, excuses, networks, lies, and tricks.

Though their (especially dalit women students) power is limited compared to all the other stakeholders of this college, they are constantly negotiating with the environment around, with their limited means. Their rage is visible in many ways such as the nicknames that they gave to the problem makers, verbal fights with the non-teaching staff.

The dalit women students are fed up with the male chauvinist mentality of this college. So they have started taking decisions on their own without compromising their dignity. For example, recently a dalit woman student went to the police station and lodged a complaint against a male student of this college for physical violence.

Though access to higher education helps them to come out of their historical siege, these dalit women students are constantly pulled behind by the norms of their family, neighbourhood, workplace, college, and other public spheres. In addition, girls and women are unnecessarily affixed as the cultural symbols of their society. For instance, their parents and immediate neighbourhood are not in parallel with the current trends of the elite ethos of South Mumbai.

The dalit women students face lots of humiliations from the upper caste students. They receive labels such as Kakubai (aunty), Behenjis (elder sisters) and scholars, for dressing in ‘non-modern’ ways. In order to overcome this humiliation, they try to balance between the two. Some of students alter their dressing styles to keep in tune with current fashion trends to college, while some of them carry extra clothes to wear in college and change before leaving to home.

Dalit women students of this college face security issues in accessing both public and private spaces. They are from slums and privacy is a huge issue in their daily lives. A dalit woman student has been relentlessly bullied by the men of her locality. Although her parents are aware of the issue, they are powerless to act against the culprits. It is because dalits are minority in that locality and registering a complaint might jeopardise their survival in that locality. At the same time, the participant is concerned that this reason should not put her education and freedom at stake and so she leaves for college early in the morning to keep herself away from such harassments.

The lack of support system and cultural capital in the public sphere make the dalit women students vulnerable. While discussing on the accessibility issues and the support system with the participants, it was noticed that their male friends play a major role in supporting them to access the public spaces without fear. In return they share their class and tuition notes with the male friends. Though the division of labour here is primarily based on the normative gender lines, the dalit women students are powerless to act against the same since they have to constantly negotiate their time between earning and education.

Conclusion

Despite having an array of difficulties, the dalit women students still manage to continue their education. The college is still seemed to be dominated by the first generation students and ghettoised by the dalits. It provides flexible environment and equal opportunities for students irrespective of their gender and class background. But these conditions do not seem to have translated into potential spaces where dalits in general and dalit women students in particular do not feel discriminated. Though education provides the opportunity to be potential skilled workers, the labour market conditions do not favour these qualifications as it is highly discriminative when it comes to dalit women. The relative positions of dalit women continue to remain subordinate that of men by reinforcing patriarchy at workplaces. While for them, class is an achieved status and is ephemeral, caste is the central phenomenon which marginalises it from the rest of the upper caste in Indian society.

For dalit women, attaining education extend to struggle which interact and intercept with the caste, class and gender stratifications, dominant structures of the wider society. Still, they have been always in the process of constructing and negotiating their identities courageously with self-esteem, self-confidence and self-determination in order to contribute to the contemporary dalit movement as well as counteracting with the roots of the caste and gender based oppressions. Be it Siddhartha College, workplace, or private sphere, dalit women continue to confront the dominant power structures enmeshed with patriarchy. Nevertheless, they believe education as a ‘magical wand’ which will take them to the other end of the marginalisation. With the help of education, dalit women could challenge the existing hegemonic educational system and its politics. It also provides them the space to relocate themselves by claiming to their rights which are controlled by the dominant sections, thus emerging dalit women’s resistance with a difference.

1. Dalit literally means ‘the broken one’, the one who is oppressed and exploited by the hegemonic Hindu social order. Though it was first mentioned by Jyotiba Phule, the term has got popularity with the Dalit Panther movement which defines it as those who experience subordination and suppression. It is interchangeably used with Scheduled caste, ex-untouchables, Bahujans.

2. External factors include the dominance of the upper caste section of the society. Whereas, the internal factors take into account the supremacy coming from the same caste.

3. Jyotiba Phule and Savitribai Phule laid the path of women’s liberation in India during the 19 th century. They fought relentlessly against the oppressive and hegemonic mechanisms of caste and patriarchy.

4. Dr. B. R Ambedkar is the father of the Indian constitution. He is seen as the emancipator of the Dalits (ex-untouchables)-the unmentioned fifth Varna of the Hindu caste system.

5. Fort is the area that comes in the south of Mumbai. South Mumbai is recognized as a nerve centre of Indian economy. It is the hub for business enterprises and foreign establishments have their branches in location. All these factors raise it as the richest urban zone of India.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)