IJDTSW Vol.2, Issue 1 No.2 pp.12 to 27, March 18th 2014

Ambedkar Social Work: Its Theory and Practice

Abstract

It is often accepted in hush tones within Indian social work circles that Social Work Education and Practice in India cannot ethically exist without accepting the ‘Ambedkar’ position. However, caste groups who currently dominate social work education, having been able to marginalize and invisibilised the ideas of Ambedkar since the beginning of professional training through sheer hegemony, have operated nonchalantly devoid of any real ethical basis for their actions. In practice their position is without any real organic politico-theoretical linkage and lacks any axiological content, sans the fact that their upper caste status provides them a religiously sanctioned power to qualify ‘what is’ and ‘what is not’ social work knowledge. As a contestation to this current politico-structural dominance, this paper is an attempt to raise the theoretical debate about Ambedkar’s ideas to its valid and rightful place in moral and political discourse within social work education. It begins by exploring his life struggles, draws out his formulations to promote an egalitarian society, extract his ideological basis for emancipation and finally culminates in a proposed theory of Ambedkar Social Work.

Introduction

The ideas of Dr. B.R.Ambedkar; India’s most intellectually refined and politically sophisticated stalwart of emancipatory politics, have universal significance and are applicable across realities irrespective of caste, gender, ethnicity and color. His ideas however, hardly reflect in professional social work teaching and practice. Unfortunately as it may be to social work knowledge generation for its own sake, this has greatly impacted the profession both in the domain of teaching content and field practice. One could even argue that the key reason for the poverty of social work education and practice in India lies not only in its borrowed knowledge from western social work, but more so because of its inability to encompass from within itself organic liberatory theory that could further theoretical advancement in more meaningful, efficacious and critical engagement (bodhi s.r, 2012).

Current professional social work in India has consciously and purposefully turned a blind eye to caste oppression responsible for exclusion and massive pauperization of peoples in India. This, despite the fact that the profession’s very foundation was built on the notion of ‘service’ to the marginalized. In such a context it becomes imperative to reformulate social work content towards emancipatory teaching and practice (ibid). Using the Ambekarite frame of analysis as articulated in many of his writings, which to date remains the most incisive and profound analysis of oppression and exclusion in India, this paper attempts to conceptualize an Ambedkar Social Work (ASW) content that is anti-oppressive and emancipatory while remaining within the theoretical confines of Professional Social Work.

The Life of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar:

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar was elected as the chairman of the drafting committee that was constituted by the Constituent Assembly to draft a constitution for independent India. He was the first Law Minister of India and was posthumously conferred the Bharat Ratna in 1990. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar is viewed as the greatest leader of the downtrodden in India. He was born on April 14, 1891 in Mhow (presently in Madhya Pradesh). He belonged to an “untouchable” caste and his father and grandfather served in the British Army. In those days, the government ensured that all the army personnel and their children were educated and ran special schools for this purpose. This ensured good education for Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, which would have otherwise been denied to him by the virtue of his caste and stigma. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar experienced caste discrimination right from childhood. After his father’s retirement, his family settled in Satara, Maharashtra. He was enrolled in the local school. Here, he had to sit on the floor in one corner of the classroom and his teachers would not touch his notebooks. In spite of these hardships, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar continued his studies and passed his matriculation examination from Bombay University in 1908 and he then joined the Elphinstone College for higher studies. In 1912, he graduated in Political Science and Economics from Bombay University and got a job in Baroda. In 1913, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar lost his father and in the same year Maharaja of Baroda awarded him a scholarship to pursue further studies in America. He reached New York in July 1913. It is often argued that for the first time in his life, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar experienced what it meant to be perceived as an equal and not be demeaned for his lower caste status. During this period he immersed himself in studies and attained a degree in Master of Arts and a Doctorate in Philosophy from Columbia University in 1916 for his thesis “National Dividend for India: A Historical and Analytical Study.”

From America, he proceeded to London to study economics and political science. However the Baroda government terminated his scholarship and recalled him back. The Maharaja of Baroda appointed Dr. Ambedkar as his political secretary but unfortunately no one would take orders from him because he was considered an untouchable. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar returned to Bombay in November 1917. With the help of Shahu Maharaj of Kolhapur, a sympathizer of the cause for the upliftment of the depressed classes, he started a fortnightly newspaper, the “Mooknayak” (The Leader of voiceless people) Janata, Prabuddha Bharat on January 31, 1920. The Maharaja also convened many meetings and conferences of the “untouchables” where B.R. Ambedkar addressed. In September 1920, after accumulating sufficient funds, Ambedkar went back to London to complete his studies. He became a barrister and got a Doctorate in science.

After completing his studies in London, Dr.B.R.Ambedkar returned to India. In July 1924, he founded the Bahishkrit Hitkaraini Sabha (Outcastes Welfare Association). The aim of the Sabha was to uplift the downtrodden socially and politically and bring them at par with others in the Indian society. In 1927, he led the Mahad March at the Chowdar Tank near Bombay, to give the untouchables the right to draw water from the public tank where he also burnt copies of the ‘Manusmriti’ publicly. In 1929, Ambedkar made the decision to co-operate with the all-British Simon Commission which was to look into setting up of a responsible Indian Government in India. The Congress decided to boycott the Commission and drafted its own version of a constitution for free India. The Congress version had no provisions for the depressed classes. These events led Ambedkar to become more skeptical of the Congress’s commitment to safeguard the rights of the depressed classes. When a separate electorate was announced for the depressed classes under Ramsay McDonald ‘Communal Award’, M.K.Gandhi went on a fast unto death against this decision. Leaders rushed to Dr. Ambedkar to drop his demand for a separate electorate. On September 24, 1932, Dr. Ambedkar and M.K.Gandhi reached an understanding, which became known as the Poona Pact. According to the pact the separate electorate demand was replaced with special concessions like reserved seats in the regional legislative assemblies and Central Council of States. Dr. Ambedkar attended all the three Round Table Conferences in London and forcefully argued for the welfare of the ‘untouchables’. Meanwhile, the British Government decided to hold provincial elections in 1937.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar formed the Scheduled Caste Federation and launched it as a forum to protect the interest of Dalit. He set up the “Independent Labor Party” in August 1936 to contest the elections in the Bombay province. He and many candidates of his party were elected to the Bombay Legislative Assembly. In 1937, Dr. Ambedkar introduced a Bill to abolish the “khoti” system of land tenure in the Konkan region, the serfdom of agricultural tenants and the Mahar “watan” system of working for the Government as slaves. A clause of an agrarian bill referred to the depressed classes as “Harijans,” or people of God. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar was strongly opposed to this title for the untouchables. He argued that if the “untouchables” were people of God then all others would be people of monsters. He was against any such reference. However the Indian National Congress succeeded in introducing the term Harijan. Ambedkar felt bitter about ascriptions imposed on the ‘untouchables’ and he himself coined many terms to refer to the ‘untouchables’.

Dr. Ambedkar was elected as Chairman of the Constitution Drafting Committee. In February 1948, he presented the Draft Constitution before the people of India which was adopted on November 26, 1949. In October 1948, Dr. Ambedkar submitted the Hindu Code Bill to the Constituent Assembly in an attempt to codify the Hindu law. The Bill caused great divisions within the Congress party. When the Bill was taken up it was truncated. A dejected Ambedkar relinquished his position as Law Minister and then resigned from the post of Law Minister. On May 24, 1956, on the occasion of Buddha Jayanti, he declared in Bombay, that he would adopt Buddhism in October. On 14 th of the stated month, 1956 he embraced Buddhism along with many of his followers and few months following this, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar died on December 6, 1956.

Key Contributions: Ideas, Framework and Perspective

Most of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s ideas are made available to us through his numerous writings beginning 1916. The ideas and perspective has been drawn from the knowledge produced by Dr. Ambedkar during his struggle for dignity. He is one of the few scholars in India who have written on almost every contemporary issues. His theorization began in 1916 till his death in 1956. He wrote extensively on the issues of caste, religion, women’s condition, minority, and many other pertinent issues and was instrumental in laying the foundations of the constitution of free India. His first book- Castes in India, published in May 1916, engages with the mechanism, genesis and development of caste as a social system in India which dominates all aspects of the Indian society. His second book- The National Dividend of India, published in 1916, was a historic and analytical study of India. His third book- Small Holdings in India and Their Remedies, published in 1917, engages with the primary sector and the distribution of land.

On 31st January 1920 he started his first weekly ‘Mook Nayak’, envisaged as a medium to articulate the voice of the ‘untouchables’ in their struggle against the age-old system of caste. His fourth book- Provincial De-centralization of Imperial Finance in British India, published in June 1921, attempts to unravel the economic situation of India during British rule. The fifth book- The Problem of a Rupee – Its Origin & Its Solution, published in March 1923, talks about the History of Indian Currency and Banking and how the Indian banking system functioned in order to sustain the Indian economy. His sixth book- The Evolution of Provincial Finance in British India, published in 1925 brings out Ambedkar’s Economic Ideas, Decentralization of provincial finance in British India, Public Finance, Economic History of India and Indian Economic Thought. His second weekly ‘Bahishkrit Bharat’, was started on 13th April 1927, aimed at debating morality and advancing the material progress of the untouchables. Another weekly ‘Janata’, began publishing on December 1930.

His seventh and most read- Annihilation of Caste was published in December 1935. This was a speech of Dr. Ambedkar that has become a historic document, dwelling on the ideas of the annihilation of caste in India. The eight book- Federation Vs Freedom, published in January 1939, lays down the birth and growth of Indian federation, its structure and the character of the federation. The ninth book- Thoughts on Pakistan, published in December 1940, engages with the politics of partition and communal politics arguing for minority protection under the new constitution in India. His tenth book- Mr. Gandhi & the Emancipation of the Untouchables published in December 1942, argued how the untouchables have been cheated by Mr. Gandhi and points out the hollowness of programs that were implemented for their development. In the comparative analysis of- Ranade, Gandhi & Jinnah, published in January 1943, he problematise the three historic personalities and does a comparative analysis of these personalities and the social impact they have made in India. His eleventh publication- What Congress & Gandhi have done to the Untouchables, published in June 1945, analyses through historical facts and figures about what the Congress and Gandhi have done unravelling their hypocrisy and double standards when it comes to ‘untouchables. His twelfth book- Who Were the Shudras?, published in October 1946 brought to light h ow they came to occupy the Fourth Varna in the Indo-Aryan Society. His thirteenth book- States & Minorities , published in March 1947, explains how the minorities should be protected and how their rights and development should be planned by the state. His fourteenth book- The Untouchable, published in October 1948 talks about the history of untouchables and how untouchables became so in India. His fifteenth book- Maharashtra as Linguistic Province , October 1948, showed the difficulties arising out of Linguistic Provinces, its advantages and the solution for its problems. This was followed by his sixteenth book- Thoughts on Linguistic States , published in December 1955, arguing about the creation of linguistic state, the advantageous and disadvantageous and the solution for the same. His last and most debated book- Buddha & His Dhamma, was published in 1957. The book was a treatise on Buddha’s life and on the basic tenets of Buddhism. Currently this book is revered by Buddhists all over the world. Finally it must be noted that in each of his books, Dr.B.R.Ambedkar lays down the most sophisticated ideas of a critical and an emancipatory politics which none can disregard if they are to seriously engage with the Indian reality.

The Making of the Indian Constitution

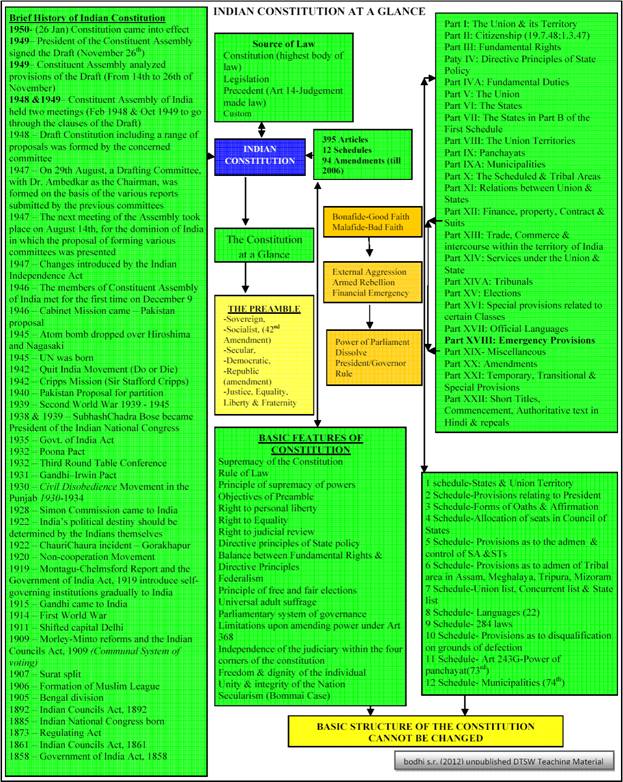

Dr.Ambedkar headed the constitution drafting committee and it is to his credit that we have an Indian constitution that is a radical breakaway from past traditions that legitimizes oppression and exclusion. He is quoted to have said ‘our object in framing the Constitution is rally two-fold: (1) To lay down the form of political democracy, and (2) To lay down that our ideal is economic democracy and also to prescribe that every Government whatever is in power shall strive to bring about economic democracy. The directive principles have a great value; for they lay down that our ideal is economic democracy’. It is the constitution that has set the new ground rules of engagement of equal citizens within the framework of democracy. Below is the Indian constitution at a glance (bodhi s.r, 2013: unpublished DTSW teaching material, TISS) for quick reference:

The Indian constitution becomes an important contribution to the social work profession as it lays the framework, rules and the ideals that social work should try to realize.

Towards Ambedkar Social Work: A Perspective from Below

Dr.B.R.Ambedkar was quoted to have said- ‘on the 26th January 1950, we are going to enter into a life of contradictions. In politics we will have equality and in social and economic life we will have inequality. In politics we will be recognizing the principle of one man one vote and one vote one value. In our social and economic life, we shall by reason of our social and economic structure, continue to deny the principle of one man one value. How long shall we continue to live this life of contradictions? How long shall we continue to deny equality in our social and economic life? If we continue to deny it for long, we will do so only by putting our political democracy in peril. We must remove this contradiction at the earliest possible moment else those who suffer from inequality will blow up the structure of democracy which this Constituent Assembly has so laboriously built up’. His analysis of the Indian reality was precise and many years after the constitution came into play we still live in a reality where his analysis and predictions still holds good.

His ideas and analysis of the Indian conditions have also had some repercussions in social work education. Arguments towards formulating an Ambedkar Social Work began earnestly in the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) since 2005, when the first school of social work in the country went through a radical restructuring of its programmes. Social Work educators who went on to lead the TISS school of Dalit and Tribal Social Work (Bodhi, 2012) pointed that while formulating a perspective on Dalit Social Work some of the earliest arguments for the same was put forth by A.Ramaiah (1998) in his article The Plight of Dalit’s: A Challenge to Social Work Profession who argued that Indian professional Social Work has ignored caste and that most professional social workers were caste-blind and inherently caste prejudiced, suggesting that the first thing that professional social workers need to seriously consider doing is to de-caste themselves. He went on to state that no social work practice paradigm could contribute meaningfully and make any real dent on the marginalized till the same is first accomplished. Bodhi (2012) picking up from this argument went on to formulating a Dalit Social Work stating that:

‘we have formulated Anti-Caste social work which is the epistemological premise of Dalit Social Work, and have positioned the same as a theoretical position that challenges the structure of graded inequality, based on purity and pollution (that is closely linked to caste and descent) and proposed a social work practice (both perspective and theory-practice) that challenges the system that dehumanises people’.

Currently Dalit Social Work although strong in premise, content and strategy still lacks a cohesive overarching framework. It is on these current formulations that the ideas of Dr.Ambedkar in the form of Ambedkar Social Work (ASW) is posit. Current Social work practice rigidifies oppressive structures, condones it through non-action, or does minimal to confront or challenge oppression, subjugation and exploitation. In this context it must be stated that the foremost aim of ASW is to unravel the basic premise and underlying thread of multiple oppressive conditioning, the interaction of various systems, sources and forms of discrimination, and to develop intervention models and practice strategies that seek to challenge and break caste oppression. The belief is rooted in the understanding that until and unless caste oppression is put to an end, social equity, social justice, growth-driven social change, empowerment and freedom cannot be attained. Thus Ambedkar social work is conceptualized building on the basic premise that caste is the root cause of all inequalities and deprivation. At the same time Ambedkar Social Work is a celebration of the strength and resilience of the Dalit Community in withstanding years of oppression and discrimination and using these strengths to re-conceptualize helping professions that would further the process of empowerment of oppressed caste. It is a paradigm shift in the identification of causal factors, where the problem is believed to lie deeply embedded in Caste Hindus. It further liberates Dalit’s from the chains of being a target group and the notion that the problem lies with individuals from the community, and that all corrective measures and intervention is to practiced and experimented on them. The shift in this conceptualization is that intervention models and strategies are now focused on every caste group including Caste Hindus and processes of how to conscientized everyone involved in the process of exploitation.

Ambedkar Social Work: Theoretical Framework

Philosophical Foundations:

Social Work needs a philosophy of its own as Ambedkar posits- ‘Every man must have a philosophy of life, for everyone must have a standard by which to measure his conduct. And philosophy is nothing but a standard by which to measure’.‘Positively, my social philosophy may be said to be enshrined in three words: liberty, equality and fraternity. Let no one however say that I have borrowed my philosophy from the French Revolution. I have not. My philosophy has its roots in religion and not in political science. I have derived them from the teachings of my master, the Buddha’. He believes that ‘The strength of a society depends upon the presence of points of contacts, possibilities of interaction between different groups that exist in it’ and in this regard he believes that ‘democracy which is not merely a form of Government but primarily a mode of associated living, of conjoint communicated experience. It is essentially an attitude of respect and reverence towards our fellow beings’.

The Socio Political and Economic Context:

ASW acknowledges’ that there is a complete absence of two things in Indian Society. One of these is equality. On the social plane we have an India based on the principles of graded inequality, which means elevation for some and degradation for others. On the economic plane we have a society in which there are some who have immense wealth as against many who live in abject poverty’.

In this context Ambedkar argues that

‘Untouchability has ruined the Untouchables, the Hindus and ultimately the nation as well. If the depressed classes gained their self-respect and freedom, they would contribute not only to their own progress and prosperity but by their industry intellect and courage would contribute also to the strength and prosperity of the nation. If the tremendous energy Untouchables are at present required to fritter away in combating the stigma of Untouchability had been saved them, it would have been applied by them to the promotion of education and development of resources of their nation as a whole’.

In this context the struggle against caste is imperative as

‘Untouchability is not transitory or temporary feature; it is eternal, it is lasting. Frankly it can be said that the struggle between the Hindus and the Untouchables is a never-ending conflict. It is eternal because the religion which assigns you the lowest status in society is itself divine and eternal according to the belief of the so-called high caste Hindus. No change warranted by change of time and circumstances is possible’. ‘Untouchability shuts all doors of opportunities for betterment in life for Untouchables. It does not offer an Untouchable any opportunity to move freely in society; it compels him to live in dungeons and seclusion; it prevents him from educating himself and following a profession of his choice’.

This is so because

‘Caste cannot be abolished by inter caste dinners or stray instances of inter caste marriages. Caste is a state of mind. It is a disease of mind. The teachings of the Hindu religion are the root cause of this disease. We practice casteism and we observe Untouchability because we are enjoined to do so by the Hindu religion. A bitter thing cannot be made sweet. The taste of anything can be changed. But poison cannot be changed into nectar.

ASW while considering the importance of religion and its role in society cautions us to the oppressive nature of its practice. In the words of Ambedkar

I tell you, religion is for man and not man for religion. If you want to organise, consolidate and be successful in this world, change this religion. The religion that does not recognise you as a human being, or give you water to drink, or allow you to enter in temples is not worthy to be called a religion. The religion that forbids you to receive education and comes in the way of your material advancement is not worthy of the appellation ‘religion’. The religion that does not teach its followers to show humanity in dealing with its co-religionists is nothing but a display of a force. The religion that teaches its followers to suffer the touch of animals but not the touch of human beings is not a religion but a mockery. The religion that compels the ignorant to be ignorant and the poor to be poor is not a religion but a visitation!

For ASW religion must mainly be a matter of principles only. It cannot be a matter of rules. The moment it degenerates into rules, it ceases to be a religion, as it kills responsibility which is an essence of the true religious act’. And thus the struggle of all those who practice ASW is to challenge ‘the sovereignty of scriptures of all religions must come to an end if we want to have a united integrated modern India’.

This is so because

Without social union, political unity is difficult to be achieved. If achieved, it would be as precarious as a summer sapling, liable to be uprooted by the gust of wind. With mere political unity, India may be a state. But to be a state is not to be a nation and a state which is not a nation has small prospects of survival in the struggle of existence. This is especially true where nationalism – the most dynamic force of modern times, is seeking everywhere to free itself by the destruction and disruption of all mixed states. The danger to a mixed and composite state therefore lies not so much in external aggression as in the internal resurgence of nationalities which are fragmented, entrapped, suppressed and held against their will…Indians today are governed by two different ideologies. Their political ideal set in the preamble of the Constitution affirms a life of liberty, equality and fraternity. Their social ideal embodied in their religion denies them.

‘History shows that where ethics and economics come in conflict, victory is always with economics. Vested interests have never been known to have willingly divested themselves unless there was sufficient force to compel them’. ‘Anyone who studies working of the system of social economy based on private enterprise and pursuit of personal gain will realize how it undermines, if it does not actually violate the individual rights on which democracy rests. How many have to relinquish their rights in order to gain their living? How many have to subject themselves to be governed by private employers?

The future India society lies in altering it through democracy.Ambedkar writes

‘A democratic form of Government presupposes a democratic form of a society;the formal framework of democracy is of no value and would indeed be a misfit if there was no social democracy. It may not be necessary for a democratic society to be marked by unity, by community of purpose, by loyalty to public ends and by mutuality of sympathy. But it does unmistakably involve two things. The first is an attitude of mind, and attitude of respect and equality towards their fellows. The second is a social organisation free from rigid social barriers. Democracy is incompatible and inconsistent with isolation and exclusiveness resulting in the distinction between the privileged and the unprivileged.

On The Concept of Self as an Agent of Change:

On the self, ASW sums up it’s believe in the words of Ambedkar who proclaimed

I hate injustice, tyranny, pompousness and humbug, and my hatred embraces all those who are guilty of them. I want to tell my critics that I regard my feelings of hatred as a real force. They are only the reflexes of love I bear for the causes I believe in and I am in no wise ashamed of it.

We need to

‘Learn to live in this world with self-respect. We should always cherish some ambition of doing something in this world’…‘It is disgraceful to live at the cost of one’s self-respect. Self-respect is the most vital factor in life. Without it, man is a cipher. To live worthily with self-respect, one has to overcome difficulties. It is out of hard and ceaseless struggle alone that one derives strength, confidence and recognition’… Man is mortal. Everyone has to die some day or the other. But one must resolve to lay down one’s life in enriching the noble ideals of self-respect and in bettering one’s human life. We are not slaves. Nothing is more disgraceful for a brave man than to live life devoid of self-respect.

For ASW ‘Freedom of mind is the real freedom. A person, whose mind is not free though he may not be in chains, is a slave, not a free man. One, whose mind is not free, though he may not be in prison, is a prisoner and not a free man. One whose mind is not free though alive, is no better than dead. Freedom of mind is the proof of one’s existence’.

Ambedkar argued-

What is the proof to judge that the flame of mental freedom is not extinguished in the mind of person? To whom can we say that his mind is free. I call him free who with his conscience awake realises his rights, responsibilities and duties. He who is not a slave of circumstances and is always ready and striving to change them in his flavor, I call him free. One who is not a slave of usage, customs, of meaningless rituals and ceremonies, of superstitions and traditions; whose flame of reason has not been extinguished, I call him a free man. He who has not surrendered his free will and abdicated his intelligence and independent thinking, who does not blindly act on the teachings of others, who does not blindly accept anything without critically analysing and examining its veracity and usefulness, who is always prepared to protect his rights, who is not afraid of ridicule and unjust public criticism, who has a sound conscience and self-respect so as not become a tool in the hands of others, I call him a free man. He who does not lead his life under the direction of others, who sets his own goal of life according to his own reasoning and decides for himself as to how and in what way life should be lead, is a free man. In short, who is a master of his own free will, him alone I call a free man.

In this sense the biggest battle to reclaim the self is the ‘cultivation of mind which should be the ultimate aim of human existence’.

On Strategy/Struggle and the Practice Paradigm:

ASW demands a seriousness of purpose and a great degree of sincerity in practice which Ambedkar himself counted as ‘the sum of all moral qualities’. His final words on practice was

‘educate, agitate and organize; have faith in yourself. With justice on our side I do not see how we can lose our battle. The battle to me is a matter of joy. The battle is in the fullest sense spiritual. There is nothing material or social in it. For ours is a battle not for wealth or for power. It is battle for freedom. It is the battle of reclamation of human personality’.

ASW believes that ‘for a successful revolution it is not enough that there is discontent. What is required is a profound and thorough conviction of the justice, necessity and importance of political and social rights’.

Ambedkar argued that ‘it is your claim to equality which hurts them. They want to maintain the status quo. If you continue to accept your lowly status ungrudgingly, continue to remain dirty, filthy, backward, ignorant, and poor and disunited, they will allow you to live in peace. The moment you start to raise your level, the conflict starts’. It is in this context that he posits that ‘You must abolish your slavery yourselves. Do not depend for its abolition upon god or a superman. Remember that it is not enough that a people are numerically in the majority. They must be always watchful, strong and self-respecting to attain and maintain success. We must shape our course ourselves and by ourselves’.

Among the many ideas that Ambedkar proposed, the one that stand out are his ideas on and about democracy and the varied formulations that followed. He state

A democratic form of Government presupposes a democratic form of a society;the formal framework of democracy is of no value and would indeed be a misfit if there was no social democracy. It may not be necessary for a democratic society to be marked by unity, by community of purpose, by loyalty to public ends and by mutuality of sympathy. But it does unmistakably involve two things. The first is an attitude of mind, and attitude of respect and equality towards their fellows. The second is a social organization free from rigid social barriers. Democracy is incompatible and inconsistent with isolation and exclusiveness resulting in the distinction between the privileged and the unprivileged.

For ASW while ‘democracy in India is only a top dressing on an Indian soil which is essentially undemocratic’… yet ASW while conceiving ‘Democracy not as a form of Government, but a form of social organization’ it sees the same as a ‘a form and a method of Government whereby revolutionary changes in the social life are brought about without bloodshed’. Within this framework however

‘What we must do is not to content ourselves with mere political democracy. We must make our political democracy a social democracy as well. Political democracy cannot last unless there is at the base of it, a social democracy. What does social democracy mean? It means a way of life which recognizes liberty, equality and fraternity as the principles of life. These principles of liberty, equality and fraternity are not to be treated as separate items. They form a union in the sense that, to divorce one from the other is to defeat the very purpose of democracy. Liberty cannot be divorced from equality, nor can liberty and equality be divorced from fraternity.

In this sense Ambedkar Social Workers are democrats in belief and in practice unshakable in their struggle through democratic means to achieve equality, liberty and fraternity. Ambedkar reminds us ‘What are we having this liberty for? We are having this liberty in order to reform our social system, which is full of inequality, discrimination and other things, which conflict with our fundamental rights’. ASW believe ‘Political tyranny is nothing compared to the social tyranny and a reformer who defies society is a more courageous man than a politician who defies Government’.

Conclusion:

The Anti-Caste movement in India is filled with an extremely rich history. Suresh Mane (2006) while documenting these historical movements, such as the Ayankali led movement in Kerala, BapuManguram in Panjab, Namasudra movement led by Haricharan and Guricharan Thakur in West Bengal, Satnami movement in central India, the self- respect movement led by Periyar in Tamil Nadu and above all the struggles of Babasaheb Ambedkar, posits that all these various strands from varied corners of the country had far and wide implications to the struggle for emancipation for the oppressed caste. In the eighties many picked up from the rich organic context laid by these movements and formulated new strategies of struggles. Foremost among them with a reached that cut across state and ethnic and caste boundaries was the movement led by Kanshi Ram. He introduced Ravidas to south India and Nandranarayan to north India. He lead dialogues among various Dalit movements from various parts of India introducing a discourse that spans 2500 years beginning with Buddha, Charvaka till the emergence of Babasaheb, positing the Ambekarite movement basically as a power struggle towards a “Rule India Movement” where power would lie in the hands of the most backward of social and cultural realities. This was so because the key reason that the Dalit movement did not picked up after the demise of Babasaheb was because the thrust was more socio-cultural than political. Kanshi Ram brought electoral power as a core component of the Dalit movement and articulated strongly for political mobilisation of Dalit’s in all over India. Today the Bahujan Samaj Party is the only national party across the India who represents Dalits as a main political force and has become the fourth largest national party. BSP had institutionalised the history of Dalit heroes and radicalised Indian history.

Debates pertaining to what category to use to represent the struggles against caste, remains in a state of flux. While writers such as Kancha Illiah argue vehemently for an inclusive Dalit-Bahujan category to confront the old-age caste system and its exploitative nature, having observed the hypocrisy of various struggles including the national movement for independence from British rule which was utterly blind to caste and merely paid lip service treatment to its annihilation (Aloysius, 2000), Guru (2005) on the other hand remains headstrong on usage of the category Dalit. This he argues is imperative in contemporary Dalit Politics. The category ‘Dalit’ has become a part of the national and global, political as well as academic agenda and has found articulation across different socio-cultural situations. The category Dalit was used by no less a person than Dr. Ambedkar himself in his fortnightly publication Bahishkrut Bharat . The term Dalit was defined by him in a comprehensive way. He says, “ Dalithood is a kind of life condition that characterizes the exploitation, suppression and marginalization of Dalit people by the social, economic, cultural and political domination of the castes’ Brahminical ideology”. While addressing his own social constituency he used the term ‘Pad Dalit’ meaning those who are crushed under the feet of the Hindu system. Further, Guru argues that the category Dalit is not a metaphysical construction, but derives its epistemic and political strength through the material social experience. This social construction of Dalithood makes itself more authentic and dynamic rather passive or rigid. The category Dalit takes ideological assistance from Buddha, Phule, Marx and Ambedkar and in the process becomes man centered rather than God centered; as the Gandhian connotation of ‘Harijan’ does. The category Dalit, in fact; promotes both the cognitive and emotional response of the collective subjects to the immediate life world and its reconstruction.

How should the issue of category be addressed, will remain a contentious issue for some more time, taking into consideration the diverse and complex nature of Dalit community in particular and the Indian society in general. However Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar’s ideas and thoughts on various social issues becomes the rich organic context to draw perspectives from. This is much more important for the profession of social work in India. His sophisticated ideas on social justice and equality are essential for social work education in India. His struggles are a constant source of inspiration to the people of India especially the vast toiling and suffering masses, because his ideas, Principles and actions continue to have relevance as the contradictions in social and economic life persist even today. His revolutionary and spirited arguments for the toiling peoples of India, who are socio-culturally discriminated, exploited, deprived and disadvantaged has changed the realities far wider than any other leader has been able to effect.

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar endeavored to set basic everlasting human values such as equality, liberty, fraternity and social justice in Indian society. These fundamental ideas and values of his life have become the fountain of inspiration self–respect, self-confidence, rationality and Practical humanism. Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar wanted to build a new India on new social order on the basis of equality and social justice, a strong united Indiafree from the burden of a history of hate and exploitation.

Ambedkar Social Work(ASW) is a pioneering indigenous theory of practice that advance social justice and social equity by taking into account systemic inequalities and discrimination based on caste, gender, culture, disability and age. Application of this very rooted liberating perspective to existing knowledge regarding practice contexts, practice-related issues, practice theories, models of intervention and personal practice experience leads to a change in the understanding and definition of social work practice. This perspective is an indigenous radical growth-oriented formulation which supports the development of personal and social change leading to a just and equitable society. The genesis and principles of bottom-up and ethno-specific social work practice are now widely recognized and accepted in social work education, training and practice. The more recent challenge in India has been to indigenize and develop anti-caste and non-western theory and practice.

However in the light of the above arguments, ASW cannot, but be based on an understanding that fundamental social work premise cannot be those have at its core the belief in Equality and Justice. As Ambedkar argues ‘Equality may be a fiction but nonetheless one must accept it as a governing principle’. On the question of Justice he posits that it ‘has always evoked ideas of equality, of proportion of compensation. Equity signifies equality. Rules and regulations, right and righteousness are concerned with equality in value. If all men are equal, then all men are of the same essence, and the common essence entitles them of the same fundamental rights and equal liberty… In short justice is another name of liberty, equality and fraternity’. ‘My social philosophy may be said to be enshrined in three words: liberty, equality and fraternity.

(+10 rating, 6 votes)

(+10 rating, 6 votes)