IJDTSW Vol.3, Issue 1 No.2 pp.11 to 24, June 2015

Locating Kamatapur Movement: Origin, Change and Continuity

Abstract

This paper is an attempt to understand the movement raised by the Koch-Rajbanshis who historically domiciled in the Brahmaputra valley of Assam for a separate Kamatapur state. This movement emerged out of the organized efforts ventured by the Koch-Rajbanshis to fulfill certain goals. The proposed creation of separate Kamatapur state by this movement comprises eleven districts of Assam and further includes six districts of West Bengal. This movement also further strives for the recognition of Scheduled Tribe status for the Koch-Rajbanshsi of Assam and the recognition of the Kamatapuri language in the Eight Schedule of the Indian Constitution. This article delved into various factors that have led to the demand for a separate state in Assam by this community. It has further examined the causal factors for the rise and growth of this movement, objectives of the movement and locates the Kamatapur movement in the contemporary times.

Introduction

Change is natural in human society. Every social system undergoes change with the passage of time. During the change process some societies faces least resistance and some have to face various organized and unorganized movements for change. This change is brought about by a collective action of people having same social belief and solidarity.

India’s North-East is one of the hot beds of social movement. Most of the movement in this region are separatist and secessionist in nature where its key demands ranges from greater autonomy to sovereignty. Many demands for a separate state including that of Kamatapur, has been raised by the people inhabiting Assam and West Bengal. Kamatapur is a separate statehood demand spearheaded by the Koch-Rajbanshi community of West Bengal and Assam.

EPISTEMOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

With a view to address the research questions, the present study is aimed at understanding the ethnic struggle of the Koch-Rajbanshis in Assam for a separate homeland called Kamatapur. The study tries to seek answers as to why such demands has aroused among the Koch-Rajbanshis of Assam mainly after 1990’s. To be precise, the study proceeds with the following specific objective: To identify the origin of Kamtapur Movement in Assam, to Identify the Movement’s objectives and to understand the current developments in the movement.

The research offers a systematic study of the ethnic identity struggle of the Koch-Rajbanshis of Assam for a demand of a separate state under the Constitution of India. The various factors that have caused to the rise of such demands and where does this movement is heading at present. The discussions derived herewith may generate fresh insights of the whole movement, which could be explored further. Keeping in mind the focus of the study, the research student has chosen the two districts of Western Assam as his universe. The research was conducted in 8 villages, 4 villages in Kokrajhar district namely Kalipukhuri, Simlaguri, Lalatari, and Chautaki and 4 villages in Chirang district namely Sakati, Rajasarang, Nehalgaon & Hekaipara of Western Assam. The sample size for Personal Interview was 40 persons (both male and female) there was no specific pattern for selection of males and females and Focus Group Discussion sample size was 20.

The process of data collection was carried out in phases. The first phase began with the secondary data collection which gave the research some ideas about the history and origin of the Kamatapur Movement spearheaded by the Koch-Rajbanshis of Assam as well as West Bengal. These processes of acquiring prior knowledge before going to the field gave the researcher immense help and streamlined the direction of the processes in locating the present context of the study.

In the second phase the focus of researcher shifted from broad theoretical and literature review to ground realities of the study, where data regarding the ongoing movement was collected from the two districts of Western Assam- Kokrajhar and Chirang.

After the decision to form Telengana state in 2013 the movement had become stronger and active and it was during the time of my data collection period many protests, rallies, strikes, meetings were held across the proposed districts of Kamatapur in Assam, so the researcher had a lot of things to observe like various strategies to mobilize people by the leaders, the participants in the rally, the objectives discussed in the meeting and the current developments in the movement. Also, to have a more in-depth understanding of the movement the researcher participated in a mass rally in Kokrajhar organized under Koch-Rajbanshi Jatiya Mahasabha (KRJM). KRJM is an umbrella body of over 11 Koch-Rajbongshi organizations from both West Benagl and Assam launching a united movement for the creation of Kamatapur.

LAYING THE CONTEXT AND THE HISTORICAL FRAME

The Koches: Racial Origin

The Koches are widely scattered and inhabit in the vast tracts of South-Asian countries like India, Nepal and Bangladesh. In India they are found in states like Bihar, West Bengal, Assam and Meghalaya. In Bihar and Assam they are categorized as Other Backward Classes (OBC), in West Bengal as Schedule Caste (SC) and in Meghalaya as Schedule Tribe (ST). In Nepal they are mainly concentrated in the Terai region of Jhapa, Morang and Sunsari districts and are termed as adivasis. In Bangladesh they are mainly concentrated in Rangpur, Dinajpur and Rajshahi districts and a small number of them are also present in Bogra and Mymensingh districts and seen as religious minorities.

The origin of the Koches has been a controversy for a long time. There is a lot of difference of opinion about their racial origin. According to Risley, the Koches, unquestionably “non-Arayan and non-Hindu”, were a large Dravidian tribe of North-Eastern and Eastern Bengal among whom there are grounds for suspecting some admixture of Mongoloid blood (Risley, 1891). Oldham also describes them as the most conspicuously Dravidian race in Bengal. Dalton has stated that the Koches were all very dark and displayed the thick protuberant lips and maxillaries of the Negro, and therefore, he considered them as belonging to the Dravidian stock. To support his claim, he forwards the opinion of a medical officer, a resident of Cooch Behar who describes the Koches of that country as having face flat…eyes black and oblique; hair black and straight, in some curling; nose flat and short; cheek bones prominent; beard and whisker rather deficient;…colour of skin in most instances black…(Dalton, 1960).

According to another group of scholars the Koches are definitely of Mongoloid stock. For example, to Hodgson, the Koches belong to the distinctly marked type of the Mongolian family. (Hodgson, 1874). He is supported by Waddel who also says that they do not belong to the Dravidian stock, but are distinctly Mongoloid ( Nath, 1989). Bachanon and the Dacca Blue Book class them with the Bodos and the Dhimals (Gait, 1926). So did Endle, who had classed the Rabhas, the Meches, Dhimals, Koches, Dimasas, Hojais, Lalungs, Garos, Hajongs and such other tribes within the fold of the Bodo race (Endle, 1911). According to Gait, there is no doubt that the Koches of Assam belong to the Mongolian rather than to the Dravidian stock. Scholars like S.K. Chatterji and D.C. Sircar hold the same view. Anthropologists of North-East India like B.M. Das also support the Mongolian origin of the Koches (Das,1997).

While such divergence of views is there, certain contemporary sources supply us with important information regarding the ethnic identity of the Koches. Thus Minhas-ud-din Siraj, the author of the Tatakat-i-Nasisri, which contains an account of the first two expeditions of Muhammad-bin-Bakhtiyar Khalji to the kingdom of Kamrupa (ancient Assam) in the first part of the 13th century, noted that during that time this region (meaning present north and north-east Bengal and Western Assam which at that time formed a part of the kingdom of Kamrupa), were peopled by the Kunch (Koch), Mej/ Meg (Mech) and the Tiharu (Tharu) tribes having Turk countenance. Ralph Fitch who visited Cooch Behar in 1585 A.D. notes: the people have ears which be marvellous great of a span long which they draw out in length by devices when they be young. Gait further informs us that this practice is still common among the Garos who belong to the Mongolian group (Nath,1989)

The religious beliefs and rites as well as in social manners and customs, similarities between the Koches and other Bodo tribes like the Rabhas were noticed by scholars like Buchanon, Martin and Risley. Buchanon even found that the language spoken by the Koches resembeled that of the Garos (Martin, 1976).

Contemporary literary sources also contain references to the Koches and their Mongoloid characteristics. Thus the Padma Purana, referring to the Koches as Kavacakas states that they had no choice of food and spoke a barbaric tongue and betrayed no sophistication in their manner. The Dharma Purana, compiled in Assam in the 17th century under the patronage of the Ahom king Siva Singha (1714-1744 A.D) also states that the Koches did violence to all kind of creatures and used to take even beef. (Kakati, 1959)

Such diverse views on the Koches, in recent years have also caught the attention of many biological anthropologists. A genetic study taken up by Guha, Srivastava, Das, Bhattacharjee, Haldar and Chaudhari, testing several genetic markers on the Rajbanshi population in the Terai and Doors region of North Bengal, concluded that Koches of Goalpara, Assam and Rajbanshis of North Bengal possessed a similar pattern of genes. The ABO blood group among Rajbanshis suggested their mongoloid connections. Further, the study also said that among the Rajbanshis of North Bengal a specific KIR genotype was found which is also found among the Tibetian population. And this genotype has not been found in any of the Indian population. (Guha, Srivastava, Das, Bhattacharjee, Haldar and Chaudhari, 2013).

Thus most of the arguments given by various scholars indicate that the Koches belong to the Mongoloid group, having their homeland in the Himalayan region, most probably in Tibet wherefrom they poured into India following probably the courses of the Teesta and Dharla. They first settled in North-Bengal and then spread gradually toward the east as well as towards the south west, where they mixed themselves up with the Dravidians. S.K. Chatterji, on geographical basis, has divided the Bodos of North-East India into two main branches: the eastern and the western, the latter according to him, being an extension of the former. According to Chatterji, the western branch included included the Koches of Cooch Behar, Kamata and Hajo; and the eastern branch, the Kacharis and the Chutiyas. But Risley who ascribes them Dravidian origin states that they had probably occupied the valley of the Gangas at the time of the Aryan advance into Bengal. Driven forward by the incursion into the swamps and forest of North and North-Eastern Bengal, the tribe was here and there brought into contract with the Mongoloid races of the Lower Himalayas and the Assam border, and its type may have been affected to a varying degree by intermixture with these people (Risley, 1891). This, however, is not tenable in the context of the foregoing discussion.

From the above analysis it appears that the Koches are of Mongoloid origin having close affinities with other tribes like the Meches, Rabhas, Dhimals, Hajongs and Garos. But in course of time and in some limited areas, they inter-married with the Dravidians and gave birth to a mixed Mongoloid-Dravidian race but having preponderant Mongoloid characters. In the middle of the 19th century Hodson observed that their number could not be less than 8 lacs, possibly even a million or a million and a quarter. In Assam proper, they numbered 3,77,808 according to the 1891 census. Their exact population in Assam is not known at present.

Designation of the Koch as Rajbanshi

The Koches migrating southward of Tibet, settling in Indian subcontinent and gradual adoption of Hinduism in these regions, the animist Koches underwent lot of hurdles trying to adjust themselves in the Hindu social order. With the formation of Koch kingdom in the 16 th century and the general masses undergoing a sanskritized process the community renounced the term ‘Koch’ and started calling themselves Rajbanshis because the Koches were seen as lower caste by the caste Hindus. Thus, instead of Koch they started calling themselves Rajbanshi, which meant belonging to the king’s race. “However, there is a contentious debate on how and when they took this name and whether the Koches as a whole renamed itself or not, especially since there is no proof. It is often said that the Koch king Vishwa Simha took the name “Rajbanshi” as part of the Hinduization process (Hunter, 1876). Moreover to find a dignified place in the caste system they also declared themselves as Bratya Kshatriya (fallen kshatriya), while from 1911 they began to boast of a pure Kshatriya origin. Interesting enough, they constantly changed their identity and for that matter asked for different names in different census: from Koch to Rajbanshi (1872), Rajbanshi to Bratya Kshatriya (1891), Bratya Kashatriya to Kshatriya Rajbanshi (1911 and 1921) and Kshatriya Rajbanshi to only Kshatriya (1931).

The claim of the Rajbanshis to be enumerated as a Kshatriya but not a tribe (Koch) began to take the shape of a movement at the time of the census of 1891 in Bengal when the census authority gave instruction to the effect that the Rajbanshi is the same as Koch. They pressed the government through persistent agitation that the Rajbanshi be recorded separately from the Koch and to be recognized Kshatriya by descent. The Rajbanshis began to emulate many Hindu manners and customs discarding their old practices in order to justify their Kshatriya appellation and Aryan origin. However in 1911 census while the first demand was conceded, the second one was turned down (Das Gupta, 1992). Thus all the efforts to get recognized as Kshatriyas had ultimately failed except successfully enlisting their name ‘Rajbanshi’ in the census separately from the tribal Koches. Thus, today we see now the usage of the term Rajbanshi in West Bengal and Bihar, Koch-Rajbanshi in Western Assam and Koches in Estern Assam and Meghalaya to refer to the same group of people.

The Kamatapur Kingdom (1250-1494)

Pala dynasty was replaced by Khen dynasty in 1250. This marked the end of the Kamarupa kingdom (earlier name of Assam) and beginning of the Kamata kingdom. The Khen dynasty also known as ‘Kamateswara’ had its capital at Gossanimari, near Dinhata, the subdivision town in Cooch Behar (now in West Bengal). This Kamatapur kingdom was an important historical, political and cultural place in ancient Assam, which continued up to the 14 th century. The rulers of Kamatapur belonged to the Khen dynasty and the Khens belonged to the present tribal communities such as Koch, Mech, Tharu, Garo, Kachari, Bhutia, Chutia and Rabha. The Khens who are believed to have come from the east India established the rule of the Khen dynasty, named Kamatapur, on the west bank of the Brahmaputra River, probably continuing from the 1250-1498 CE (Debnath, 2008).

The Koch Kingdom (1498-1949)

The Kamta kingdom was eastablished at the time of the Khen kings such as Niladhwaj, Chakradhwaj and Nilambar with its capital at Kamatapur. It is stated by many historians that the Koch dynasty followed the lineage of Nilambar. The Knen king Nilambar of the Kamta Kingdom was defeated in a battle in 1498 by Sultan Hussain Shah of Bengal who ousted the Khens and assumed the title of ‘Conqueror of Kamata’. After the defeat of the Kamata king Nilambara, there prevailed some sort of anarchy in the west part of Kamatapur kingdom. During this short period the petty Bhuyan Chiefs, who were once established by the Kamarupa-Kamta kings, rose into prominence and tug-of-war began to continue among them for supremacy. But this state of things could not continue for long time, and a leader from the Koch tribe, King Biswa Singha son of Haria Mandal established an independent Koch Kingdom in the beginning of 16 th century. Even though this period, this territory was referred as Koch Kingdom but the Koch kings never renamed the territory as such, it was called by its old name Kamatapur. However in 1586 following the death of King Nara Narayan, who succeeded King Biswa Singha, the kingdom split into two parts: Koch-Behar and Koch Hajo. Koch Hajo soon got absorbed by the Mughals and lately Ahoms. However Koch Behar (Cooch Behar) survived till 1949 under various Koch kings under its last Koch king Jagaddipendra Narayan when the merger with India was accepted after the partition and finally, it became a district of West Bengal on 1 st January 1950 (Debnath, 2008).

LOCATING KAMATAPUR MOVEMENT: ORIGIN, CHANGE AND CONTINUITY

From the data that has been collected from the field, from various interviews and group discussions with the respondents, mainly three broad themes for discussion has been derived pertaining to the origin of the movement in Assam.

The Cooch Behar Merger Agreement Act, 1950

Looking at the origin of the movement the Cooch Behar Merger Agreement Act of 1950 that made princely state Cooch Behar a district of West Bengal, has been seen one of the most initial and primary reason for the demand of separate statehood by the Koch-Rajbanshis. However, the demand for formation of Kamatapur on the basis of this Cooch Merger Agreement Act has been mainly emphasized by intellectuals and leaders of the community. The community at large is unaware of this Act. The Cooch Merger Agreement Act got faded with time in Assam as the Koch-Rajbanshsis accepted the ‘Assamese’ culture in Assam. It is only now in contemporary times this Merger Act has been brought into the limelight again to strengthen the demand of separate Kamatapur state. The betrayal of the Koch-Rajbanshis following this Act is now openly discussed in the meetings of various organizations fighting for the cause of the Koch-Rajbanshsis in Assam.

Cooch Behar remained as a Princely State during the British rule. After Independence Pandit Jawahlal Nehru the then Prime Minister of India requested the kings of all native states, to get merged with the Indian Union. The issue of merger of the princely state Cooch Behar started a tug of war among the political leaders in North Bengal. Over the merger issue there emerged five opinions among the leaders:

Historically the merger of Cooch Behar princely state as a district of West Bengal has been one of the important factors responsible for the emergence of the Kamatapur movement in Assam and West Bengal. On request from Bidhan Chandra Roy, the then Chief Minister of West Bengal, to the government of India for merger of Cooch Behar with West Bengal, the then Home Minister, Sarder Patel, sent Akbar Hyder Ali, the then Governor of Assam , to Cooch Behar to seek the public opinion on the issue. Considering Mr. Ali’s report submitted on 29 th June 1948 Sardar Patel wrote to the government of West Bengal that the leaders of the Cooch Behar People’s Association were not satisfied on the merger issue and they wanted a Cooch Behar State. Later, even Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru announced public meeting addressed in Kolkata to take into account the people’s wishes on the question of merger of Cooch Behar. However, Dr. Bidhan Chandra Ray who was not satisfied with the Prime Minister’s statement sent to the Government of India some important letters with a request for merger of Cooch Behar with West Bengal.

However, on request from the government of India, the then Maharaja of Cooch Behar handed over the Cooch Behar princely state to the Central Administration of India for happiness and prosperity of the ‘Praja Mandal’, i.e., the people of Cooch Behar, on 11 th September, 1949 under a special agreement which led the government of India to appoint a Chief Commissioner to take all its responsibilities. As, per the merger agreement, Sardar Vallabhai Patel, the then Home Minister of India, sent a letter to the Chief Commissioner of Cooch Behar on 11 th September 1949, stating that Cooch Behar was handed over to the Central Administration of India as a state on the condition that government of India would take into account all the socio-economic problems of the people of Cooch Behar and solve them with a kind heart so far as possible and soon. Therefore, the people of Cooch Behar trusted the Government of India for solution of the problems of Cooch Behar administered as a Union Territory which they obviously wished for. As a result, there was started the central administration of India in Cooch Behar from 12 th September 1949 under the Chief Commissioner, V.I. Nanjappa.

On November 1949, the Chief Commissioner, Mr. Nanjappa, communicated to the Joint Secretary, Government of India, that the Hitasadhani Sabha wanted Cooch Behar’s inclusion in Assam whereas some of the Hindus and Muslim Koch-Rajbanshis demanded for inclusion of the Dooars areas in Cooch Behar state because once upon a time the Dooars was a part of Cooch Behar.

Then, Dr. Bidhan Chandra Roy again wrote letters to the Government of India for inclusion of Cooch Behar princely state in the state of West Bengal immediately, otherwise it would merge with Pakistan. After having been administered as a Union Territory for total three months and nineteen days finally, on 1 st January 1950 Cooch Behar was included in West Bengal as a district on the condition that the Government of West Bengal would take all necessary measures to improve socio-economic condition of the people of Cooch Behar. But such promise by the West Bengal government was never fulfilled. (Das, 2013).

States Reorganization Commission which was set up by Government of India in 1953 to fulfil the people’s aspirations for reorganization of states on cultural and linguistic basis once again made the people of Assam and North Bengal pounder over whether Cooch Behar should merge with West Bengal or with Assam, or whether it should regain the status of a Union Territory. The outcome was that:

Resultantly, at the time of the operations of the States Reorganization Commission, the Koch-Rajbanshis of Assam and Bengal failed to mobilize themselves into a movement for separate state on the basis of their ethno-cultural and linguistic identity, due to lack of political intellectuals in the community as, in course of time, they have been Assamised in Assam and Bengalized in Bengal. (ibid).

However, the Koch-Rajbanshis could not digest the inclusion of the erstwhile Cooch Behar princely state as a district of West Bengal because it lowered its dignity and honour by making it a district from an independent state. Thus, identity crisis and socio-historical and political subordination impelled the Koch Rajbanshis into the Kamatapur Movement in Assam.

Denial of Scheduled Tribe Status

The denial of Scheduled Tribe (ST) status is one factor that almost everyone has agreed upon on the birth of Kamatapur Movement in Assam. For the general respondents ST status for the community has mainly been asked by the community for economic upliftment and reservation. But for the community leaders and intellectuals the ST status has something more to it. It is also the eligibility for the community to avail the various provisions of the 6 th Schedule of the Constitution.

There has been a long standing demand by communities in Assam namely, Tea-tribes, Koch-Rajbanshis, Chutias, Ahoms, Marans and Mattaks for their inclusion in the ST list under the constitution of India. Among these communities, the demand of the Koches is the oldest. The Koch-Rajbanshi Sanmilini demanded ST status for the community for the first time in 1968. In a meeting held by Koch-Rajbanshi Sanmilini in Coutara, Kokrajhar on 7 th -8 th February, 1969 the demand for ST status for the community became a formal agenda of the Koch movement in Assam.

In 1994, a study carried out by the Tribal Research Institute under Assam government found adequate justification for inclusion of the community in the ST list. Subsequently following this report even Register General India (RGI) gave a ‘no objection’ for the inclusion of the community in the ST list. Following this, “The Constitution (ST) Order (Amendment) Bill, which called for the inclusion of the Koch-Rajbanshi community in the ST list, was introduced in the Lok Sabha in 1996. The bill was then referred to a 15 member select committee, which also recommended the granting of the ST status to the community. Consequently, the Constitution (ST) Order (Amendment) Ordinance, 9 of 1996 was promulgated as the Parliament was not in session at that time. The ordinance stipulated that the Koch-Rajbanshis be included in ST (Plains) list of Assam. Though the ordinance was re-promulgated three times, it could not take the shape of law as the above mentioned Bill was allowed to lapse in April 1997.” (Roy, 2014). The recommendations made by various agencies have been overlooked and have never been taken seriously by both the state and the central government. All these have led to feeling of alienation and anguish among the community members. Calling of bands, road blockade, railway blockade, rallies, etc by various Koch organizations particularly in Western Assam today have become a routine to push forward their demand.

Moreover in relation to Bodoland Territorial Autonomous Districts ( BTAD) district they also revealed that the Koch-Rajbanshis and the Adivasis have been purposely denied the ST status even though they fulfil all the criteria to avail the tribal status. This is because if the Koch-Rajbanshis and Adivasis would get the ST status than they would be capable in standing for council elections in the seats reserved for ST candidates (30 reserved seats for ST out of total 46 seats).

Youths and students mainly interviewed mainly saw ST status for the Koch-Rajbanshis for getting reservation in jobs and government educational institutions. Dipankar Roy a post-graduate student of Guwahati University, who hails from Hekaipara village of Chirang district comments

“Today in education sector the competition is very tuff. Only few of the Koch-Rajbanshis can afford for higher education because education has become costly. I am only the second male from my village that has completed graduation. Girls even don’t study till high school. In government jobs too they ask for bribe. We are poor nor can we pay bribe nor do we get any reservation facility. See our Bodo friends; they have excelled a lot by getting reservation. We too want ST status for a good future.”

Plight of Koch-Rajbanshis in BTAD

The Bodo Accord signed on 10 th February 2003 between the Government of India, Government of Assam and surrendered Bodo Liberation Tigers (BLT) militants have been severely criticized and challenged from its time of inception by non-Bodo communities living in BTAD.

The separate homeland for the plain tribes of Assam on the North bank of Brahmaputra called ‘Udayanchal’ started with the formation of Plains Tribal Council of Assam (PTCA) in 1967. However, the demand of Udayanchal was later given up after the PTCA joined the Janata Government in 1978-1979 (Misra, 1989). Failure of PTCA gave rise to All Bodo Students’ Union (ABSU) which was also formed in 1967, to take up the issue of separate homeland for plain tribal. Failure to mobilize other plain tribes for a new movement, ABSU under the leadership of Upendra Nath Brahma sought for a full-fledged homeland for the plains tribes of Assam called ‘Bodoland’ from 1987. In its 92 points Charter of Demands presented to the Assam government, the last demand sought for creation of separate State for the plains tribes of Assam. Even though the movement started with a democratic manner but later the movement took a violent turn with the formation armed militant group called the Bodo Security Force (Bd.SF). This led to ethnic cleansing of other indigenous communities like Adivasis, Assamese, Koch-Rajbanshis, Muslims and Bengalis in the proposed Bodoland territory who opposed the creation of a separate homeland exclusively for the Bodos. For example according to Kanteshwar Ray a respondent of Simlaguri, during the ethnic cleansing drive by the Bodo militants a total of 642 Koch-Rajbanshi families were displaced from various parts of Kokrajhar who are now presently taking shelter in Bidyapur Relief Camp in Bongaigaon district of Assam.

To end the violence and come to a permanent settlement the central government and state government signed an agreement with the ABSU known as Bodo Accord in 1993. The Accord promised forming a Bodo Autonomous Council (BAC) comprising geographical areas between river Sankosh and Mazbat/river Pasnoi having more than 50% tribal population and also to have contagious area villages having less than 50% of tribal population would also be included under BAC. However, the Assam government unilaterally demarcated and declared the boundary of BAC due to lack of census data, this was opposed by ABSU and subsequently the Accord failed (Nath, 2003). This failure led to rise of insurgent groups like BLT which demanded for a separate Bodoland state and National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB) which demanded for a sovereign Bodoland. And subsequently Assam saw a series of ethnic cleansing in the demanded Bodoland territory. To name a few the 1993 and 1998 Bodo-Santhal ethnic conflict and the 1996 the Bodo-Muslim ethnic conflict, this killed hundreds and rendered homeless to thousands from both the communities (Hussain, 2000).

Thus, to stop the violence the government appealed the BLT for a ceasefire in 1999 which the BLT agreed. And on 10 th February, 2003 new Bodo Accord was signed between the central, state and representatives of BLT under the modified provisions of 6 th Schedule of the Constitution of India.

The Bodo Accord, 2003 led to the formation of Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC) which comprised of 3,082 villages under four newly formed districts Kokrajhar, Chirang, Baksa and Udalguri. The BTC would have legislative, executive, administrative and financial powers with respect to the subjects transferred to it. This Council has 40 elected and 6 nominated members. Out of the total 46 members, 30 will be from Schedule Tribes, 5 will be non-tribals, 5 from the general category and 6 would be nominated by the government from among unrepresented sections.

Formation of BTC has been severely criticized by non-Bodos living in BTAD. Sanmilita Janagosthiya Sangram Samiti (SJSS) which is an umbrella organization of 18 non-Bodo organizations which also the Koch-Rajbanshis are a part of has been very critical about the formation of BTC. The Adivasi Student’s Association (ASA) has also threatened to take up arms if the BTC is not dissolved. Presently the SJSS and Assam Public Works a NGO working on conflict issues in Assam have also announced to move to the apex-court and challenge most of the clauses included in the Accord.

O-Bodo Suraksha Samittee an organization of non-Bodos in BTAD has also launched an anti-Bodoland Movement in Assam. The main argument of the non-Bodo communities in BTAD have been that how can a 25 % population be made to rule over the rest 75 % of population (The Telegraph 8 th May, 2013, The Shillong Times 5 th November, 2013). Also, in a public lecture delivered by Prasenjit Biswas on “Politics of Small State Movements: Situating Telengana Effect in North-East India” in Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai in December, 2013 Mr. Biswas argued that in BTC a total of 1,764 villages have opposed to be part of BTC.

Moreover, according to the 2001 Census of India the ST population of Kokrajhar district which came under the administration of BTC in 2003 has only 33.7 % of ST population. So, it seems logically incorrect that in every village of Kokrajhar district there is more than 50% ST population. Thus, inclusion of non-Bodo villages under the BTC and further domination of the Bodos on other communities including the Koch-Rajbanshis has caused unrest in BTAD area. Since data was also collected from BTAD districts namely Kokrajhar and Chirang, the people in this two districts sees the Kamatapur movement as the only solution out of BTC in particular and Assam in general.

Kamal Rajbanshi a respondent of Simlaguri says,

“first Kamatapur was taken by Assamese and now by the Bodos. All the districts of BTAD were part of earlier Kamatapur kingdom. The decedents of Bijni kingdom of the last Koch King Bhairabendra Narayan is still alive. How can Kamatapur be ruled by the Bodos?”

Bhabesh Chandra Ray Secretary of Kamatapur Association says,

“ there are several reasons for the growth of violence in the BTAD area (since 1990 till date). First, a tendency has developed on the part of the Bodos to make ‘Bodoland for Bodos’ through a process of ethnic cleansing. After the 1990s the Bodo movement was mainly under the control of the leadership of extremist groups which were resorting to ‘ethnic cleansing’ of the non-Bodo groups. The Bodo agitators realised that for a ‘homogenous Bodoland’ the demographic picture of the proposed Bodoland must be altered in their favour; otherwise the prospect of formation of a separate Bodoland was bleak. They, therefore; targeted and attacked the non-Bodos, especially the Bengali Muslims, Assamese, Koch-Rajbanshis and Adivasis. The provision of the Bodo Accord, which stipulated the enlistment of the villages with 50% or above Bodo population, led a section of the Bodos to target the Muslims and Adivasi villages, where the Bodo-majority could not be proved. The underlying motive was to create a homogenous Bodo inhabited area”.

Rina Ray who had participated in the Koch-Rajbanshi Jatiya Mahasabha (KRJM) held in Kokrajhar says

“today due to huge inflow of funds from the central government BTAD areas are fast developing but if one sees closely only areas predominantly inhabited by Bodos are benefiting. Other communities like Koch-Rajbanshis which also form a major chunk of the BTAD population have been deliberately kept out from being beneficiaries of such funds. We have seen no development in our village after formation of BTC nor have we benefitted from any project implemented in BTAD”.

Most of the youths which were interviewed said that whatever jobs are vacant in Bodoland is filled up by the Bodos. Bodos gets the first priority. Also, for any contract works the Bodos are preferred. Unemployment has become a major problem for the non-Bodo youths in BTC.

AKRSU Mahila Samittee President Mrs. Purabi Sarkar said that the dominance by Bodos on Koch-Rajbanshis’s language, culture and history have led to angry outburst among the Koch-Rajbanshis inhabiting in BTAD. Instances like,

Chandan Rajbongshi an employee at the Government Forest Department of Kokrajhar says,

“there has been a lot of inter-district migration. Many Koch-Rajbanshi families have brought land in nearby districts like Bongaigaon and Dhubri. People have sold their ancestral land and have settled outside BTAD region. He said his neighbour has sold his 10 bighas of land in Kokrajhar just for Rs. 10 lakhs (which is very less) and had brought 1 bigha of land in Bongaigaon. Also, BTAD receiving huge amount of funds the income of the Bodos have also risen. Mr. Rajbongshi said that poor non-Bodo families are continuously selling land to the Bodos because the Bodos are ready to give whatever amount the Non-Bodos are asking for the land.”

Mr. Khagen Singha a youth from Hekaipara says,

“Today the Koch-Rajbanshis lives in threat in BTAD. Nobody has the courage to openly speak up to the policies of the Bodos. The surrendered BLT who now runs the BTC has still not submitted their weapons. These weapons were also used against the Muslims in the recent Bodo-Muslim ethnic conflict. Security for the non-Bodos does not exist in BTAD”.

Thus with the creation of BTAD which was opposed from the beginning of its formation and later the dominance of the Bodos on other communities like the Koch-Rajbanshis have stirred the Movement for a separate state among the Koch-Rajbanshis more.

Positioning the Kamatapur Movement: Perspective and Politics

Today various organizations have been formed by the Koch-Rajbanshis to lead the Kamatapur Movement like the AKRSU, Kamatapur Association, Cilarai Sena, All Kamatapur Students Union (AKSU) and insurgent group like Kamatapur Liberation Organization(KLO) and political organization like Kamatapur Progressive Party.

In Assam the father figure of all the likeminded organizations is the All Koch Rajbanshi Students Union (AKRSU). The objectives of the Kamatapur Movement as defined by the AKRSU are:

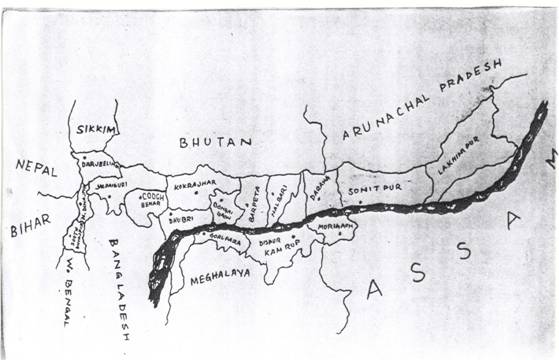

Figure: Map of proposed Kamatapur state issued by AKRSU.

Present status of Kamatapur Movement

After the Cooch Behar Merger Agreement Act, 1950 the demand for a separate state for the Koch-Rajbanshis has been again voiced after 40 years in Assam. Till now 23 years have passed since the formation of AKRSU has demanded the formation of Kamatapur. However, till now none of the demands have been met by the government but if one sees at the ground reality, this movement has been successful to blow away the dust of the ‘Assamese’ identity from the Koch-Rajbanshi identity. Today, many Koch-Rajbanshis do not claim themselves to be Assamese. They assert their own identity as Koch-Rajbanshi. Infact, the movement has been successful in raising the consciousness of the Koch-Rajbanshi people and consolidating their identity on ethnic lines.

The ongoing Kamatapur Movement in recent years is also seen to be taking a violent turn. From my respondents I also came to know that many youngsters are joining the banned outfit of the community Kamatapur Liberation Organization (KLO). Even though this outfit took birth in Jalpaiguri district in West Bengal but now it is also spreading its roots in Western Assam. The only cause for this violent turn in the movement is the neglect of the government to resolve the grievances of the indigenous Koch-Rajbanshis. Another, reason can be seen that the government resolving the demands of the Bodos and bringing a militant group to rule the BTC has also given a wrong impression to various communities in the region. Most, of the communities in Assam including the Koch-Rajbanshi today are seen threatening the government that if needs are not met by a democratic struggle than the community will adopt an armed struggle to meet its demands.

Almost, once or twice a week various organizations who is running a democratic struggle for a separate state is seen to be declaring bands, road block, railway block, etc in Assam. The present Kamatapur movement is still an ongoing one and it certainly shows a trend of becoming more vibrant and violent in nature.

Conclusion

The inspiration for the present Kamatapur movement has been drawn from the historical Kamatapur kingdom which was established by Sandhya Ray in 1250 and later re-established by Koch King Biswa Singha in 1498, which came to an end with the signing of the tragic Cooch Behar Merger Agreement Act in 1950. Inclusion of Cooch Behar with West Bengal was strongly condemned by the Koch-Rajbanshi population of Assam. But this betrayal by the West Bengal government and the Central government was forgotten over time as the Koch-Rajbanshis subsequently got subsumed to the ‘Assamese’ identity in Assam.

The demand of the Koch-Rajbanshis of Assam which started with claiming for ST status in 1967, the negligence of the government to accommodate them in the ST list even after being recommended by several nodal agencies and the inclusion of the Koch-Rajbanshi dominated areas in BTC against steep resistance of the community and further dominance by chauvinist Bodos has again given birth to old demand of Kamatapur in Assam.

Today more and more Koch-Rajbanshi organizations are being formed in the region to raise the issues of the Koch-Rajbanshis. Also, KLO spreading its roots from West Bengal to Assam’s soil is being seen as a major concern.

The Kamatapur movement is also seen by other communities in BTAD as a resistance to the Bodoland Movement. Recently the All Adivasi Students Association, All Assam Bengali Students Union (AABSU) and All Assam Minority Students Union (AAMSU) in BTAD region have extended their support for the creation of Kamatapur. Thus, today the movement is seen engulfing a larger population and becoming more violent in the coming days.

The society in North-East in general and Assam in particular is a highly heterogeneous in nature, language and communities differ after travelling a few kilometers. Looking at the provisions of the Bodo Accord, 2003 is-à-vis the demography configuration of Kokrajhar district of Assam from the 2001 census, the Accord changes the whole definition of democracy. It takes away the political rights of a majority section of the people who are also indigenous to the land. In such situation, upsurge by non-tribals is usual. Thus, one can say that the 6 th Schedule of the Constitution of India has been legitimizing exclusion in the region.

This exclusion will also hold true if we see the range of ethnic-conflicts that has taken place in Assam in the recent past-most of the ethnic-conflict in the state has occurred in the Schedule areas like Karbi-Anglong, Dima-Haso and recently Rabha-Hasong due to such discriminatory policies of the 6 th Schedule. The implementation of 6 th Schedule of the Constitution in these areas has taken the lives of many. The 6 th Schedule is infact another face of the ‘Divide and Rule’ policy of the Indian government.

Thus, it becomes crucial to look critically and examine how this policies which are regarded as ‘pro-tribals’ functions in ground.

Bisua is a cultural festival celebrated by the Koch-Rajbanshis.

Reference

Aggarwal, J.C & Agrawal S.P 1995. Uttarakhand: Past, Present, and Future. New Delhi: Concept Publishing.

Ahuja, R. 2001. Research Methodology, Jaipur: Rawat Publications.

Barua, Indira & Das, D.D. 2002. Ethnic Groups, Cultural Continuities and Social Change in North East India. New Delhi: Mittal Publications.

Baruah, S.L. 2012. A Comprehensive History of Assam. Guwahati: Munishram Manoharlal.

Bera, K. Gautam. 2011. Social Unrest and Peace Initiatives. Guwahati: EBH Publishers.

Bhattacharyya, S.N. 1927. A History of Mughal North-East Frontier Policy. Calcutta: Punthi Pustak.

Dalton, E.T. 1960. Descriptive Ethnology of Bengal. Vols.1 & 2. Calcutta: Indian Studies.

Das, Arup. Jyoti. 20009. Kamatapur Movement: Taking Inspiration from the Past. Souvenir, North East India History Association, 129-139

Das, Arup. Jyoti. 2011. Kamatapur and Koch-Rajbongshi Imagination. Guwahati: Montage Media.

Das, B.M. 1997. Brahmaputra Valley Population. New Delhi: Kitab Publishing House.

Das Gupta, Ranjit. 1922. Economy, Society and Politics in Bengal: Jalpaiguri 1869-1947. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Das, N.K. 1994. Ethno-Historical Process and Ethnicity in North-East India, in Journal of the Indian Anthropological Society.

Das, Prashanta. 2013. Kamatapuri Movement: A Sociological Review. Guwahati: MRB Publishers.

Dasgupta, S.M. Yasin. 2003. Indian Politics: Protests and Movements. New Delhi: Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd.

Debnath, Pankaj.Kumar & Bhattacharjee, Subhasis (eds.). 2008. Economy and Society of North Bengal. Kolkata: Progressive Publishers.

Denisof, R. Serge. 1974. Sociology of Dissent. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Inc.

Datta, Sreeradha, 2004. The Northeast Complexities and Its Determinants. New Delhi: Shipra Publications.

Endle, S. 1975. The Kacharis. Delhi: Munshiram Monoharlal.

Erikson, E.H. 1970. Reflections on the dissent of contemporary youth. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 51, 11-22.

Flick. U. 1998. Introduction to Qualitative Research, New Delhi: Sage Publication.

Gait, E.A, 1963. History of Assam. Calcutta: Thaker Spink & Co Pvt. Ltd.

Guha, Das, Bhattacharjee, Haldar & Chaudhari. 2013. A Comparative Analyses of the ABO,

KIR and HLA Loci among Rajbanshis of North Bengal Region, India. Annals of Pharma

Research , 01(01), 18-24.

Gurr, T.R. 1970. Why Men Rebel. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hudson, B.H. 1847. The First Essay on the Koch, Bodo and Dhimal Tribes. Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press.

Hussain, M. 2000. State, Identity Movements and Internal Displacement in the North-East. Economic and Political Weekly, 35(51), 4519-4523.

Hussain, M. 2006. Internally Displaced Persons in India’s North East. Economic and Political Weekly , 41(5), 391-393.

Kakati, B.K. 1959. Aspects of Early Assamese Literature . Guwahati University.

Martin, M. 1976. The History , Antiquities, Topography and Statistics of Eastern India. London: W. H. Allen and Co.

Marx, Karl & Engels, F. (eds.) 1848. Communist Manifesto. London: Red Publication.

Medhi, Rohini. 2013. The Struggle for Koch-Rajbanshis ST Status. In Talukdar Jogen & Talukdar, Samar (Eds). Biswa Mahbir Chilarai aru Kamrup-Kamata (pp. 335-339). Nalbari: Biswa Mahabir Chilarai Smriti Rakhyan Samittee.

Merton, R.K. 1957. Social Theory and Social Structure. New York: Free Press

Misra, Udayan. 1989. Bodo Stir: Complex Issues, Unattainable Demands. Economic and Political Weekly. 24 (21), 1146-1149.

Miri, Mrinal. 1982. Linguistic Situation in North East India. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company.

Mukherji, Partha. N. 1987. Study on Social Conflicts: Case of Naxal bari Peasant Movement. Economic and Political Weekly. 22 (38), 1607-1616.

Nath, D. 1989. History of Koch Kingdom (1515-1615), Delhi: Mittal Publication.

Nath, M.K. 2003. Bodo Insurgency in Assam: New Accord and New Problems. Strategic Analysis, 27 (4), 533-544.

Oomen, T.K. 1977. Sociological Issues in Analysis of Social Movements in Independent India. Sociological Bulletin. 26 (1).

Pakem, B. 1990. Nationality, Ethnicity and Cultural Identity in North East India. Guwahati: Omsons Publications.

Rajkhowa, J.P. 2013. Koch-Rajbanshis at the Cross Roads . In Talukdar Jogen & Talukdar, Samar (Eds). Biswa Mahbir Chilarai aru Kamrup-Kamata (pp. 320-334). Nalbari: Biswa Mahabir Chilarai Smriti Rakhyan Samittee.

Rao, M.S.A. (1979), Social Movements in India, Vol.1. New Delhi: Manohar Publication.

Ray, Nalini. Ranjan. 2007. Koch Rajbanshi and Kamatapuri: The Truth Unveiled. Guwahati: Vicky Publishers. Risely, H.H. 1981. Tribes and Caste of Bengal, Vol.1. Calcutta: Firma KLM Pvt. Ltd.

Roy, H. 2014. Politics of Janajatikaran: Koch Rajbanshis of Assam. Economic and Political

Weekly , 49(47).

Samuel, A. Stouffer. 1949. The American Soldier. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Shah, Ghanshyam. 2012. Social Movements in India. New Delhi: Sage Publication.

Shields, Patricia. 2013. A Playbook for Research Methods: Integrating Conceptual Frameworks and Project Management. New York: New Forums Press.

Singh, Bhupinder. 2002. Autonomy Movements and Federal India. Jaipur: Rawat Publications.

Smelser, Neil. 1963. The Theory of Collective Behavior. New York: Free Press.

Stein, Lorenz Von. 1852. The History of Social Movements in France 1789-1850. Trans and ed, by Kaethe engelberg, 1964. The Bedminster Press, Totowa, N.J.

addell, L.A. 1975. The Tribes of the Brahmaputra Valley: A Contribution on their Physical Types and Affinities. Delhi: Sanskaran Prakashak

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)