IJDTSW Vol.1, Issue 2 No.2 pp.23 to 30, May 2013

Caste Conflict and Peace Process in Uthapuram (2008 – 2012): Lessons for Social Workers

Abstract

Dalits in Tamil Nadu have been subject to social, economic and political exclusion and discrimination. Up until the 1990s, caste Hindus controlled land, water and other resources which form the basis of survival of Dalits. Hence the dalits were subservient to the caste Hindus. Since the 90s there has been notable change in socio-economic relations between Dalits and caste Hindus, mainly the Other Backward Castes [OBCs]. Dalits have benefitted from inclusive policies and have become less dependent on caste Hindus for their livelihood – this has resulted in an assertion for socio- political equity. Caste Hindus see this assertion as a challenge to their hegemony which has resulted in several caste conflicts in the recent past. This paper documents the caste conflict which took place between 2008 and 2012 in Uthapuram, Tamilnadu. The twists and turns in the conflict are documented using historical research methodology, primarily newspaper evidence. The paper highlights the peace process and lessons learnt from the conflict. It also offers strategic perspective on tackling caste conflicts in other regions.

Introduction

Dalits in Tamilnadu have been subjected to social, economic and political exclusion and discrimination. Prior to 1990s, caste Hindus held land, water and other resources which form the basis of survival of Dalits. Hence Dalits were subservient to the caste Hindus (Viswanathan, 2005)

However, since the 1990s there have been notable changes in socio-economic relations between Dalits and caste Hindus, mainly Other Backward Castes (OBCs). Dalits have benefitted from inclusive policies and have become less dependent on caste Hindus for livelihood (Pandian, 2000). This has resulted in Dalit assertion for socio – political equity. Caste Hindus perceive the assertion of Dalits as challenge to their hegemony. This has resulted in several caste conflicts in the recent past.

The state government and the police machinery was either supportive to the caste Hindus or was a meek spectator to the caste conflicts and the resultant violence that followed in many places. For instance, during the Karanai village incident which took place in Chingalpet District of Tamilnadu the revenue officials and police joined hands to crush the assertion of Dalits. On 10 October 1992, Dalits were protesting against the desecration of Dr. Ambedkar’s statue. To quell the dissent, the sub collector, Mr. Romesh Meena gave a firing order and without warning the police officials opened fire. Two Dalit community leaders were shot down and fourteen innocent people were injured. Further, the defiant sub collector ordered the police to arrest hundred and thirty Dalits (Devakumar, 2007). The government was tight lipped on the incident.

During the panchayat elections in 1996, the Tamilnadu state government was a docile bystander to the Thevars (a powerful OBC community) decree that no Dalit should file nomination papers, lest they be killed. Due to the diktat, no one came forward to contest in the Pappapati panchayat elections in Madurai. The Thevars later fielded two dummy Dalit candidates and helped them win the election. After the swearing in ceremony both the dummy candidates resigned (Sumathi et al., 2005). The State Election Commission, government bureaucrats and policy makers witnessed this incident quietly.

In fact, the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) government went to the extent of canonising caste Hindu leaders by naming roads, road transport corporations, districts and schemes after them. The Thevar Guru Puja, a caste/ religious program to honour Muthuramalinga Thevar – a strong religious-nationalist leader of the Thevars – was sponsored by the state government itself (Pandian, 2000) resulting in resurgence of caste pride in the Thevars. But this has not restricted Dalits from asserting their rights in the recent past.

According to M.S.S. Pandian (2000), “Dalits have started to assert their rights by seeking equal honour in temple festivals”. Thus temple vicinity and festivals have become the breeding ground for violent conflicts. In this paper, the authors have documented the fourth Uthapuram Caste Conflict (2008-2012) in Madurai which revolved around a temple issue. With newspapers emerging as an alternate research tool in social science research, the authors have relied on newspaper facts for the study.

The Case of Uthapuram Conflict

Uthapuram is a village of around 700 families in Madurai district of Tamilnadu. Dalits outnumber the other castes in the village; yet they are not allowed to use community hall, village squares, burial grounds, common property resources etc. They are also not allowed to hold the ceremonial ropes in temple festivals (Karthikeyan, 2008).

According to the locals, Uthapuram has witnessed four caste clashes in the recent past. The first occurred in 1948, followed by clashes in 1964, 1989 and 2008. After the 1989 clash, the caste Hindus built a 600 meter wall which covers their residential area. The wall passes through land which is meant for common use by people of all castes (Karthikeyan, 2008 a). It also restricted Dalits to access the main road directly. Dalits have to use a circular route and walk few more miles to reach the main road (Mohan, 2008). But after the third caste clash in 1989, the Dalits did not confront the caste Hindus over these exclusionary practices.

After a period of twenty years, the fourth clash began in 2008 and continued in various ways for the next five years. It started in April 2008 when the caste Hindus electrified the 600 meter wall using iron rods. The Dalits were initially reluctant to confront them but the Tamilnadu Untouchability Eradication Front (TUEF), CPI (M), CPI and All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA) vehemently opposed the caste Hindus (Venkatesh, 2008). These organisations registered their protest in the state assembly.

Following the state wide agitation by progressive organisations, the electricity minister of Tamilnadu ordered removal of the electric power line (Karthikeyan, 2008 b). Sensing the right opputunity, these organisations along with the local Dalits pressed for demolition of the caste wall. The Dalits staged a demonstration infront of the Taluk office demanding the pulldown of the wall (Viswanathan, 2008).

The district adminstration intervened and demolised parts of the wall on May 6 th to provide passage to the Dalits. In retaliation, some caste Hindus submitted their ration cards i to the Tehsildar (Mohan, 2008). Others left the village enmasse during the demolition and did not return for three weeks (Viswanathan, 2008).

The state was pushed to a tough situation of pacifying both the communities. The district administration persuaded the caste Hindus to return to the villages. The caste Hindus sought three demands for maintaining normal relations – a patta for the temple, a police outpost and construction of new houses for the 1989 clash victims (Viswanathan, 2008).

The state set up a police outpost and pacified the caste Hindus but the outpost was set up in a building belonging to the dominant caste association, thereby prohibiting the Dalits to have access (Reporter, 2009 b). Through persuasion a road was built at the demolition site but caste Hindu women started to wash their clothes on the road, thereby creating unrest (Sampath, 2009).

In September 2009, the conflict reached its peak. The intensified conflict was now on the denial of rights to Dalits to access the peepal tree opposite the Muthalamman temple ii. The caste Hindus were attached to the temple but the religious practices of Dalits centred around the peepal tree.

The caste Hindus built a compound wall around the temple and the peepal tree to restrict Dalit access. The caste Hindus also imposed constraints by not allowing the Dalits to stand under the shade of the tree while waiting for buses and other transport services (Reporter, 2009 b).

Meanwhile, violent fights began after altercation over painting the temple wall (Reporter, 2009 a). Several people were injured on both sides. During this time the police took the side of caste Hindus and commited atrocties.

Ms. Ponnuthaai, the District Secretary of AIDWA filed a petition in the Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court demanding judicial enquiry on the police atrocities. The High Court appointed a commision to study the atrocities. The report of the commision brought to light the assault on Dalits and recommeded fifteen lakh rupees as compensation to the affected. The Tamilnadu government objected the finding, but the High Court gave an interim order to pay compensation of ten lakh ruppes to the victims (Sampath, 2009). Meanwhile, Ms. Nagalakshmi, the convenor of Pengal Iyakka Peravai (a women’s rights organisation in Madurai) filed a PIL to direct the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments (HRCE) Department of the state government to take over the Muthalamman temple (Reporter, 2009 b). The caste Hindus objected to the PIL fervently and sought police security to conduct the temple festival.

Aware of a potential high intensity conflict, the high court directed the Madurai District Collector and the Superintendent of Police to convene a peace meeting to amicably solve the issue (Reporter, 2009a). Asra Garg, the Madurai District Superintendent of Police took special interest in the issue. He formed a peace committee consisting of representatives from both the communities (Ganesan, 2011). Village leaders Marimuthu, Murugesan, Ponniah, Sankaralingam, Aadhimoolam and Somasundar were part of the core committee (TNN, 2012).

Several rounds of negotiation took place between 2009 and 2011. The caste Hindus laid down their claims and the Dalits put forth their views in the committee meetings which were convened at regular intervals. The police officials and the revenue administrators also participated in the meetings. Asra Garg, the Madurai District Superintendent of Police took a social justice stance and facilitated the meetings.

The core committee members realised that the conflict started because of restriction on temple participation. Several debates took place and the caste Hindus decided to end the conflict by allowing Dalits to participate in the temple (Ganesan, 2011). This was a major breakthrough.The caste Hindus laid down two demands for this to happen. Firstly, they requested that the temple administration be with the caste Hindus as it is their heriditary temple. Secondly, the caste Hindus wanted cases registred against them withdrawn (Ganesan, 2011). The Dalits accepted the deal. An agreement was prepared and approved by the villagers. The agreement was signed by both the parties on 20 th October 2011 (TNN, 2012 a). On the basis of the deal, the Dalits were allowed to enter the temple on 10 th Novermber 2011 (TNN, 2012 a). The kumbabishekam (consecration) of the temple was held during June 2012. During the festival the caste Hindus received the Dalits in the temple. Thus, the Dalits were able to participate in the kumbabishekam after a span of 50 years (Karthikeyan, 2012).

Meanwhile, other contentious issues were also sorted out by the peace committee. The first was the issue of common bus shelter. Based on the accord signed by both communities, the court directed the government to take up the construction of the bus shelter. Rengarajan, the Member of Parliament allocated five lakh rupees from the Local Area Development fund for the construction. Appreciably, land for the bus shelter was donated by the caste Hindus (Raj, 2012). Another minor altercation which arose due to encroachments along the the new pathway was also solved by the peace committee. Finally, both the communities decided to withdraw all the court cases filed in connection with the conflict. They approched the Deputy Inspector General and the Superintendent of Police to withdraw the cases (TNN 2012 a).

The High Court appreciated Mr. Asra Garg for creating unity among Dalits and caste Hindus (TNN, 2012b). The press appreciated him for his bravery with compassion (TNN, 2012 c). The locals appealed to the Chief Minister to keep the transfer of Asra Garg in abeyance. Interestingly, earlier in his career Asra Garg (a 2004 batch IPS officer) was conceived as a threat by caste Hindus. He was nearly killed on many occasions as he challenged the status – quo in the villages (Kumar, 2011). Now the same people are fond of him because he helped solve a 50 year old caste conflict. The High Court disposed the writ petions filed by Dalits and was very vocal in its final judgement. It reaffirmed that people can find solutions to problems. It gave direction to the authorities to implement the accord of the people. The court also gave orders for withdrawal of the criminal cases pending against both communities (Raj, 2012). The judgement was welcomed by all stakeholders including social movements, left wing political parties, police, press and people at large.

Observations

During the 1990s and after, the state (i.e, the provincial government of Tamilnadu) has been silently watching caste conflicts. It had to face of the wrath of the SC/ST Commission in the Pappapati incident (Sivagnanam, 2003) in order to standup to the situation. Even in the case of Uthapuram which has witnessed four caste clashes, the state was not proactive. In fact, only after the hue and cry in the legislative assembly did the government take measures to cut the power supply of the caste wall.

During and prior to the 1990s, the progressive movements and left political parties did not participate in the Dalit cause much effectively. After the resolution adopted by the All India Convention on Problems of Dalits organised by the CPI(M) in Feburary 2006, the involvement of the party and allied social movements have tremendously increased. This infact resulted in the formation of the Tamilnadu Untouchability Eradication Front (TUEF) in 2008. Since then, the TNUEF, CPI (M), CPI and AIDWA have worked together effectively. This has been a welcome change in Tamilnadu. The victory in Uthapuram village can be partly attributed to this change.

One more notable change is in the way the Judiciary conducted itself in the Uthapuram conflict . Right from the time Ms. Ponnuthaai, the District Secretary of AIDWA filed the petition in the Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court the agency was commited to the cause of Dalits and stood for justice. This is a tremendous change as compared to earlier years. Police and revenue officials have not changed much, but individuals like Mr. Asra Garg who fought the 50 year old caste conflict with conviction and determination stand out.

Lessons for Social Workers: The Process Model

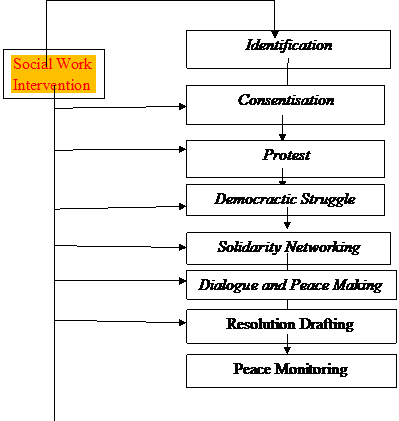

From the Uthapuram conflict it is possible to develop a process model of social work intervention while working on issues of caste atrocities, caste discrimination and exclusion. The authors have developed the following model with an eight stage intervention process

Fig1: Caste Conflict Resolution Model

Stage 1: Identification

The first and foremost role of the social worker is to identify caste based discrimination and exclusion in the locality. After identifying the issue it is necessary to work closely with like minded progressive organisations and Dalit social movements.

Stage 2: Conscentisation

In the second stage, it is important for social workers in particular and the movement or collective they are associated with conscientise the local Dalit community about their own problems. This is essential as it is important for the community to understand its own issue and take a lead role in the struggle for justice.

Stage 3: Protest

The third and important stage in the process is protest. It is a way of making our opinion heard in public. Protest can be in the form of a march, picketing public offices, organising mass rallies, etc.

Stage 4: Democractic Struggle

Alongside protesting against the disriminatory and exclusionary practices, it is also important to seek justice by utilising the pillars of democracy – the judiciary, executive and legislature. Social workers should not undermine the role of these agencies in the struggle for justice.

Stage 5: Solidarity Networking

Social workers should identify committed individuals and solidarity actors working in various agencies – the police, revenue adminstration etc., and seek their help at appropriate levels. This is essential to tilt the momentum in favour of the oppressed.

Stage 6: Dialogue and Peace Making

By the fifth stage in all probability the oppressors may try to negotiate and make amends with the oppressed. Social workers should use the opportunity without fail. Social workers should make all efforts to create an environment for diologue and peace making. During the process equal representation from both the parties should be sought. The social worker should act as a facilitator to help understand the issue and sensitise both parties. The key objective of this process is to arrive at key decisions.

Stage 7: Resolution Drafting

Once key decisions are made the social worker should write down the resolution agreement and get the assent of all the people so that peaceful co-existence is restored.

Stage 8: Peace Monitoring

The last but important stage is the process of peace monitoring. Social workers should form a peace monitoring committee consisting of community members, collective representatives, police, revenue officials and solidarity workers. The monitoring should be for a minimum period of two to three years. This will help maintain peace in the locality.

Highlights of the Model:

Conclusion

So far there has been no documetation of social work interventions in caste conflicts. This is mainly because of the fact that social workers are non responsive to caste based discrimination and exclusion. Social work educators are also silent on the issue. The “syllabi which gives a fair understanding of the vision and commitment of the academic disciple towards its proclaimed goals is also conspicuously mute on Dalits and social justice” (Ronald and Laavanya 2011: 36). This situation should end. Therefore it is important for Dalit (anti-caste) social work to document innovative interventions and practices on the field. This will help institutionalise Dalit (anti-caste) social work. ( Ramaiah, 1996; bodhi, 2010, 2012; Ronald 2012).

Endnote

1 The ration card is a form of citizenship identity and submission of the card is symbolic to relinquishing the citizenship as a mark of protest

2 The Muthalaman temple was built on a poromboku land and the caste Hindus were requesting patta for the temple during conflict period.

Bibliography

Bodhi, S.R. (2010). The Emergence of Dalit and Tribal Social Work, Interview with Bodhi by Sruthi Herbert, Marian Journal of Social Work, 3, 14-27.

Bodhi, S.R. (2012). The History of Dalit and Tribal Social Work, Interview with Bodhi by Nilesh Kumar Thool, Indian Journal of Dalit and Tribal Social Work, 1 (1), 91-102.

Devakumar, J. (2007). Caste Clashes and Dalits Rights Violations in Tamil Nadu. Social Scientist, 35 (11/12, 39-54.

Ganesan, K. (2011, November). Frontline. 28 (23).

Karthikeyan, D. (2008 (a), April 17). Electrified wall divides people on caste lines. The Hindu .

Karthikeyan, D. (2008 (b), April 18). The dividing wall remains but looses its string. The Hindu .

Karthikeyan, D. (2012, June 30). Uthapuram Dalits take part in temple consecration. The Hindu .

Kumar, P. C. (2011, May 6). Asra Garg IPS addresses long-term caste issues after playing his role during election. The Weekend Leader .

Mohan, G. (2008, May 7). Finally ‘Caste Wall’ that divided a village is breached. The Indian Express .

Pandian, M.S.S. (2000). Dalit Assertion in Tamil Nadu: An Exploratory Note. Journal of Indian School of Political Economy , 12 (3&4): 501-517

Raj, S. D. (2012, May). Wall vs. Will. Frontline,29( 9).

Ramaiah, A. (1996). ‘The Plight of Dalits: A Challenge to Social Work Profession’ in Murli Desai, Anjali Monteiro and Lata Narayan (Eds.) Towards People-Centred Development- Part 1, TISS, Mumbai.

Reporter. (2009 (a), September 15). High court orders peace panel meet. The Hindu .

Reporter. (2009 (b), September 17). PIL seeks governement take over of Uthapuram temple. The Hindu .

Ronald, Y and P.V. Laavanya. (2011). Dalits, Social Justice and Social Work Education: Content Analysis of Social Work Syllabi. Journal of Madras School of Social Work, 6 (1&2), 31-42.

Ronald, Y. (2012). Dalit Social Work: Emerging Perspectives and Methods from the Field. ACUMEN: Marian Journal of Social Work, 4 (1), 16-27.

Sampath, P. (2009). Recent Struggles and Victories on Dalit Issues. Poeple’s Democracy, 33 (36).

Sivagnanam, K. (2003). Local Governance: Tamil Nadu Experience, Chennai: Planning Commission’s Chair and Unit, University of Madras, Chennai.

Sumathi, S., and Sudarsen, V. (2005). What does the New Panchayat System Guarantee? A Case Study of Pappapatti, Economic and Political Weekly, 40(34), 3751-58

TNN. (2012 (a), Feburary 15). Uthapuram castes away ugly past. The Times of India .

TNN. (2012 (b), April 28). HC pats Asra Garg for uniting Dalits and caste Hindus. The Times of India .

TNN. (2012 (c), May 26). Its now Garg’s turn to bid adieu to Madurai. The Hindu .

Venkatesh, M. R. (2008, May 1). Caste torment, from south to north communist war against ‘Berlin Wall’. The Telegraph .

Viswanathan, S. (2005). Dalits in Dravidian Land – Frontline reports on anti-Dalit violence in Tamil Nadu (1995-2004), Navayana Publishing, Pondicherry.

Viswanathan, S. (2008). The fall of a wall. Frontline, 25 (11).

(+2 rating, 1 votes)

(+2 rating, 1 votes)