IJDTSW Vol.6, Issue 1, No.1, Pp. 1 To 19, August 2019

Protected: Muslim Migrant Workers In Aari Embroidery Sector Of Mumbai

Abstract

Livelihood based migration and its impact on Urban Sociology have been heavily discussed in recent times. In most of the cases the socio-economic conditions of an individual play a heavy role in determining migrating patterns, causes and underlying reality. The dual identity of being a Muslim and being an ‘outsider’ is maintaining a limitation where the relationship between Muslim migrant workers and opportunities due market behaviour becomes complex. Muslims are heavily dependent upon the unorganised sector and Aari embroidery is a part of the same sector. Earlier, technology influenced larger production with negative impact on the workers engaged in the sector but the recent phenomenon of Demonetisation and Taxation system has further compounded the matter. The current livelihood situation has become quite unsustainable with a low amount of wage received and seasonality attached to the textile industry. With the overarching developments of neoliberalism and quest for cheap labour in developing countries has turned themselves as a part of the phenomenon called ‘Sweatshops’. In essence, the author wants to argue that fluctuating market behaviour has affected them heavily with special reference to the Demonetisation, taxation reforms and global market trends. Taking note on the contextual reality of Mumbai and the status of Muslim migrant workers the present study revolves around the livelihood related complexities.

Mohammad Imran Pursued his Masters in Social Work from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai

Migration, Demonetisation, Muslim Peripheralization, Unorganised Sector.

Introduction

The economic activities of cities and urban centres is contributing a huge share in India’s economic development. The share of Urban economy has increased from 29 percent in 1950-52 to 62-63 percent in 2007, this trend is expected to be increased by 75 percent in 2021 (Planning Commission, 2008: 394). The neoliberal economy has impacted almost every section of the population which has resulted in the migration with pulling and pushing almost every section of the society. In contemporary times, migration has been a part of major studies centered upon the urban society of India in relation to changing economic patterns and dynamics (Mishra, 2016). Simply, it is defined either as a temporary or a permanent movement of a person from one place to another with reference to the ‘place of origin’. There are four major types of migration defined in terms of distance and administrative cum regional boundaries i.e. intra district, inter-district, Interstate and abroad. In the Indian context, interstate migration has been crucial in showing the economic gaps between regions and how it is becoming factors in the mobility of ‘masses’. Marriage and Education and search of livelihood opportunities are the prominent factors of the in all type of migration within Indian territory. In fact, the dynamics of migration patterns are not only impacted by the Push and Pull factors but there are several other reasons which comprise the factors behind the migrating reasons. With the advent of liberalised economy and fluctuations in the global economy, the migrating patterns have also shown variations but the Rural to Urban migration is still a central phenomenon (Paul et al., 2011).

In the Indian context, Maharashtra is the biggest recipient of migrant workers while Uttar Pradesh and Bihar have the largest share in outgoing migrants (Mishra, 2016). In the case of livelihood induced migration, unorganised sector appeared to be the biggest receptor of migrants. Thus, the study also focuses on one of the most unorganised means of livelihood and has an ample amount of Muslim migrant workers associated with i.e. Aari embroidery. Fluctuating market trends along with factors running within the textile industry have impacted a lot to the Aari embroidery workers. In quest of exploring the multiple hardships, this study focuss upon enumerating the economic and spatial marginality along with the socio-political elements based upon the dual identities i.e. religious and being a non-local resident. An attempt has also been made to evaluate the security nets centred upon migrant workers in terms of reach and impacts made by them. Livelihood conditions, accessibility to basic resources, and experiences of day to day life in terms of changes or variations felt due to the migrating process were focused as key elements of analysis of the situation. In addition to this, the advancement of machinery, process of globalisation and emerging phenomenon of precariousness among the low-income working class have been discussed in the context Aari embroidery work.

The purpose of study looks into two major aspects, evaluation of the phenomenon of migration and relation of the livelihood with vulnerabilities faced by Aari embroidery workers. This study, attempts to see whether the process of migration and opting Aari embroidery work as means of livelihood is benefitting the Muslim migrants or not. Centred around the urban sociological grounds the study reflects the relationship of politics, state and marginalisation of the target population. The central theme has captured the lives of migrants and how their ‘outsider’ identity is creating hurdles in accessing basic citizenship rights guaranteed under the Constitution of India. Various empirical studies have shown that the trend for livelihood induced migration in low-income jobs is getting affected by the process of stagnancy. Which is producing financial inability to help out people to come out of poverty.

Migration: Background and Prospects

Migration is a social process which has multiple impacts in the forms of variations in the receiving society as well as the place from where the population is outflowing. There have been two major streams which support and opposes the process of migration in multiple terms i.e. Migration Optimists and Migration Pessimists (Haas, 2010). The Optimists mainly support through the functionalist and neoclassical school of thought while the Pessimist’s orientation comes through the Neo-Marxist features. Migration optimists show that migration promotes modernisation and equality through ‘Brain Gain’ for the sending societies. On the other hand, Migration Pessimist views migration as a process which promotes disintegration and deepens inequality by influencing the dynamics of sending society through receiving societies with the course of ‘Brain Drain’ (Taylor, 1999). Meanwhile, it is also seen as the redistribution of resources with a flow from richer to poorer places with increasing the earnings of the marginalised population (Harris, 2005). In a similar fashion, trickle down effect is also used as a theory to showcase the positive impacts of interstate migration. Migration from lesser industrialised areas impact positively in labour market, income and expenditure pattern along with enhancing the scope of investment among the migrating section in the source region (Jha, 2008). Migration is quite integral to human development and its impact cannot be fully explained in either terms but a holistic and contextual review is a better way to analyse the impacts. Thus, a contextual theorisation should be produced in order to evaluate the phenomenon of migration (Haas, 2010).

Theorising the process of migration has been very debatable specially when it comes to define it through the intentionality of the migrating population. With the passage of time various theories and interpretation has emerged in this field which very based on multiple empirical works focusing either on micro or macro elements. The model or theories which have been developed and widely used are Gravity Model, Zelinsky Migration Transition Model, Intervening Opportunity Model, Human Capital Model, Relative Deprivation Model and World System theory. Considering the target population and its context the author has found the Neoclassical model close to the migrating pattern. This theory was developed by Todaro (1969) and has two further divisions i.e. Neoclassical Macroeconomic Model and Neoclassical Microeconomic Model. The Macro model puts weightage on factors like wage differences along with ratio of labour and capital generation, and higher probability of getting a job as major cause of migration. While the Micro model focuses on the labour market, individual’s rational and cost-benefit calculations and likelihood of finding work. In a nutshell, the Neoclassical theory of migration highlights a direct relationship between the expected returns with the of size of population migrating towards a particular region(Harris and Todaro, 1970).

Migration in India is not a newer phenomenon but the livelihood induced migration is somehow marked by the industrialisation brought in by British rule. In support of this argument theories like the crash of ‘Built-in Depressor’ (Thorner, 1956), Drain of Wealth (Naoroji, 1901) are being profoundly put up. The enhanced industrialisation process and continued distress in the agrarian sector has produced multidimensional variations in the process of migration in India. In the context of metropolitan cum industrial cities like Mumbai unemployment and proximity of getting high wages to become as one of the main reasons for ‘Pushing’ a larger chunk of the population especially young from the economically backward regions of the country. Apart from this, Socio-cultural factor like caste, gender and religions along with violence sometimes plays a crucial role in migration (Srivastava, 2011). The migrant population working in the Aari embroidery sector has a twofold experience attached to their process of migration i.e. religion and regional disparity. In terms of religion, they saw the limitation of opportunities and administrative biases towards their development while the regional disparity of their region is somehow embedded with the limited employment availability and those with good wages. Association with farming is not much producing well-being of the family of migrants which somehow ‘pushes’ them towards metropolitan cities like Mumbai.

Internal Migrants in India: A Critical Perspective

As per the official website of Registrar General and Census Commissioner, a migrant is defined as follows: When a person is enumerated in the census at a different place than his / her place of birth, she/he is considered a migrant2. There is also a gender element in migrating pattern of India, marriage and working as a domestic worker are most common reasons for migration among females. While males have a majority in moving for livelihood and education. The census data of 2001 revealed that a total of 309 million of the Indian population were defined as migrants which have increased to 453 million in 2011 showing a decadal growth of 44.2% between the same period (Haan, 2011). Although the trend has fluctuated in every aspect over the last few decades and diversification has occurred with regard to the direction of moving. The question of identifying the migration prone group and finding reasons behind migration has a complex answer. It varies in accordance to the different contexts and situations and distinct groups migrate which is prompted by different opportunities, capabilities and differentiated access (ibid.). Though internal migration in developing countries like India has not emerged out of the image of survival strategy, in fact, it is seen as a result of both poverty and prosperity (Das & Saha, 2013). A central theme which emerges out as the reason for migration in India is basically comprised of the rural to urban migration and the wage differentiation and continued agricultural distress is seen as one of the most necessary parts of it. Along with this the rising regional disparity and structural transformation in Indian society in terms of educational attainment, social group status and per capita consumption had also played an important role in it (Mishra, 2016: 03).

India has a strong wavelength in rural to urban migration out of which migration towards metropolitan cities like Delhi, Mumbai and Kolkata has a good number.The case of labour mobility is also seen in terms of the above reasons but in the recent time, it is also getting characterised by chronic lack of employment and farmer suicides (Abbas & Varma, 2014). In fact, a strong and positive correlation is found between the gross and net migration rates with the Net State Domestic Product (NSDP) (Srivastava, 2011). Although it has been seen that the migration from North India towards the South Indian states (Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka) has increased over the past two decades3. Despite coming to metropolitan cities, the livelihood quality and risk associated with it get added with the living condition and accessibility to resources add problems to most of the migrant workers of the unorganised sector in Mumbai. Similarly, the Aari embroidery workers are cut off from social security nets and due to the higher living cost, they have to stay back in the workplace only which is quite inhuman.

Unorganised Sector and Migrant Workers

Since, 1971 the proportion of the agrarian workforce has seen a continuous decline whereas the strength in non-agricultural sectors has seen a rise in its strength (Bhattacharya, 1998). Along with this the ‘reforms’ of economic liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation have enhanced the process of migration of every kind workers and on the basis of several indicators, most of the rural in-migrants get absorbed in unorganised sector (Pattanaik, 2009). Generally, migrant workers get employed in order to fulfil the bottom end tasks which have the highest probability of risks which the local would not wish to handle (Breman, 1996).Due to the increased labour force and informalization of the economy migrant worker who got absorbed in the unorganised sector are often paid below than the market rate or minimum wage (Kundu & Sarangi, 2007). Despite having a good probability of getting jobs in modern cities the probability of coming out of misery is also very low. The precarious situation of the migrant allows the employers to escape providing the basic amenities for them which includes health, education of children, living and working condition (Borhade, 2016). In many cases, their continuous presence in labour migration produces a situation of underemployment (sometimes disguised) and unemployment. Such type of livelihood uncertainties forces migrants to live low standard and quality of life in the metropolis (Paul et al., 2011). Along with this the migrant labour face multiple vulnerabilities in terms of accessing basic entitlements and social security benefits. In most of the cases, exclusion of migrants from such type of basic resources emerged due to lack of proper certificates and biased treatment from the authorities due to their identity of being an outsider. Earlier several legislations were made to address the issues related to jobs of migrants like Interstate Migrant Workers Act, 1979 (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of services) but its poor implementation didn’t make any change on the ground realities (Borhade, 2016) and necessity has emerged to Amend this law. Though the Unorganised Workers’ Social Security Act 2008 which guarantees a person for basic requirements need to be reviewed after a decade of its enactment since none of the studied cases of migrant workers is known to any of the schemes. In fact, there is a sense of threat among Aari embroidery workers that they might be charged higher and due to the paperwork associated with any scheme.

Muslim Migrants in Mumbai

Mumbai is considered the commercial capital of India. It generates 40% of Maharashtra state’s revenue, 33% of All India income tax collection, 60% of all India custom duty, 40% of country’s foreign trade (MCGM, 2005). There are many more facts are sufficient to explain why migration is a common phenomenon of Mumbai. The city has its own history of migration starting from the colonial era to the current neoliberal era. The nativist politics and the binary of “insider-outsider” is a common to day to day politics of Mumbai despite the fact that migrant population in Mumbai constitutes about 37% of the total population and out of which 70% are immigrants from Maharashtra4. And those who are from Non-Maharashtra regions are not in good conditions and remains entrapped in the vicious cycle of poverty due to their nature of occupation and their struggle for legal status (Abbas, 2016).

Muslims in Mumbai (Greater) constitute around 21% of the overall population and majority of them lives in ghettoized urban spaces5. 1992 Bombay riots are considered as the most disastrous event for Muslims of Mumbai not in geographical terms but also in economic terms (Contractor, 2012).Most of the Muslim localities had the impression of being a den of illegal and criminal activities which is reinforced by popular media sources and films (Shaban, 2008). Though encroachment of neoliberal policies and withering away of welfare state along with the development of communal populism is considered as the primary factors which led to the exacerbation of crime and social conflicts in metropolitan cities like Mumbai.

Due to the feeling of Karahiyat [Urdu: hate, disgust] for Muslims in Mumbai, a deterrence gets developed with regard to their engagement in small business and ultimately push them towards the occupation with low social status and which provide meagre economic earning. Muslims of Mumbai are mainly concentrated in the repair, processing occupation and their represented is quite low even in jobs like security guards, courier services and shopkeepers (Mhaskar, 2013). In a similar fashion, Muslim migrant workers of Aari embroidery have continuously pushed on the margins. Entrepreneurship opportunities are quite limited and on top of that the socio-political structure of the city doesn’t allow them to go beyond a ‘permissible limit’.

Aari Embroidery and Mode of operation in Micro-Units

Etymologically the French word broder is considered as the root word from which the word embroidery is derived. Traditionally embroidery is described as an art in which design is made on cloth by needle and thread that stretches with antiquity. In fact, unlike other arts embroidery also reflect the cultural traditions of the people (Bhushan, 1990: 01). In the Indian context, embroidery and its sophisticated space and works are quite gendered and in most of the cases, mastery in various art forms is given to men (Wilkinson-Weber, 1997). But when it comes to evaluating an embroidery work from an Indian point of view, it is the designs and fine patient workmanship which has more considerations than the background (Sinha, 1926).

Evolution of Aari embroidery is linked to the Sindh area currently in Pakistan) and it was the Mochi (cobbler) community which paved the way for this sort of embroidery work. Aari embroidery gets evolved when the people of the same community used a refined version of the same tool (Aari) and make a shift from leather to other silk articles. Somehow this innovation gave a way to cobblers to leave their caste occupation. Later on, the same embroidery designs were greatly followed by Ahirs and Kunbis of western India (Bhushan, 1990: 21). Although, with the advent of machines and advancement of technologies this embroidery gets moved from handwork to machine work.

Taking note on the definition of micro-enterprises, it is quite clear that the target population is attached in the profession through micro-level enterprises (OECD, 2004). The units that have been operating the target area of Mumbai majorly consists of migrant workers ranging between 6-10. The mode of operation is in the chain system where the Aari workers are supposed to draw the predefined designs on the cloths. In fact, the units are themselves are part of chains where clothes are being supplied from the above and after finishing the embroidery work they are supposed to give it back to the contractor. It was found that most of the workers were unaware of the persons involved in supply-demand chain. They only know about the amount they will pay for doing per square inches of work. They have a strong disconnection with the overall profit earned by the contractor and the rates are quite cheap as compared to the cost of the final product. Along with this, there is a huge impact of the seasonality attached to the profession whose causes and impacts will be explained in the later sections.

Research Questions

-

What are the changes in the Muslim migrant worker lives and livelihood in the Aari embroidery sector after migration?

-

What are the impacts of economic policies of Demonetisation and Goods and Services Tax?

-

How the changed socio-political along with technological advancements are affecting the livelihood prospects of Muslim migrant workers in the Aari embroidery?

Methodology

The research was mainly concerned with the livelihood struggles of Muslim migrant workers in the Aari embroidery sector. Therefore, two main features of the whole scenario were selected to be covered thoroughly i.e. migrating process and vulnerability in sustaining livelihood. The Neoclassical model was applied to analyse the migrating phenomenon while the Sustainable Livelihood framework was applied to analyse the livelihood related concerns. The area of study was one of the ghetto of Mumbai and has changed a lot since the 1992 Bombay riots. Taking note on the population and sensitivity attached to it, the author could not mention the exact location of study.

Field based observations and dialogue with the residents were crucial in getting in touch with the migrant workers. Thus, purposive sampling was used to collect the data where identity of being a Muslim and Non-Maharashtrian became a determining factor apart from engagement in Aari embroidery work. Thirty in-depth interviews were carried out along with five case studies. The case studies were selected from the in-depth interviews and conducted to support the quantitative data. A balance between quantitative and qualitative aspect was taken care of which is crucial for a mixed method research. Frequency distribution, cross-tabulation and standard deviation were the major tool of analysis of quantitative data through the application Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). While the qualitative data was purely covered under the lines of content analysis of the transcripts of the case studies.

Major Findings and Discussion:

-

Socio-Economic Status of Aari Embroidery Workers

Evaluating the background of workers through multiple features provides a picture of the role of different identities and how identities are constructing a specific environment of marginalisation. Apart from it, this helps in providing crisp details of social and economic mobility one has achieved or aspired to achieve through migration. Taking note on the type of skill and labour required for the Aari embroidery, it is expected the age group of the workers shall not be more. Thus, with the data it is quite evident and almost 77 percent of the workers are less than the age of 32. Two-thirds of the total respondents were unmarried. There is no engagement shown by the female in this sector and cent percent of the respondents were male. Educational attainment of the more than 90 percent of workers ranges below the matriculation. Despite being non-literate or having a low level of educational attainment the workers were able to perform the skills smoothly. Majority of the migrant workers found to be from the Seemanchal area of Bihar and its adjacent area of West Bengal. The respondents were mainly from Katihar, Purnia, Kishanganj districts of Bihar state and Uttar Dinajpur district of West Bengal. Among them, 90 percent said to be from the rural localities from these areas. If someone sees the social background then it was unprecedented that the majority of the respondents claimed to be from the Shaikh community which somehow considered under the Ashraf category of Indian Muslims. Though anthropologist like Francis Buchanan (1809-10: 196-197) has noted that the non-artisan castes in Purnea used to call themselves as Shaikh. For the Shaikhs in the region agriculture was considered as the better mean of livelihood than the others (Anwar, 2001: 95). Hence, the Ashraf status of migrant workers is ambiguous. It was also claimed that Aari embroidery is not a job which is inherited by the previous generations and there was no connection with the textile industry in the place of origin. Though one can relate that caste as a crucial factor which builds a social network that is operating as an underlying agent of the migration and has been proved empirically several times. In fact, it is the close circle of an individual which affects the trajectory of one’s decision and in this case, relatives/friends or any type of personal contact is becoming a source of getting jobs in an urban location like Mumbai. Such a situation directly indicates that the regional disparity and financial vulnerability is working as the more effective factor rather than social causes. While looking towards the financial conditionality of the migrant workers the scene seems to be growing in a negative sense. Around half of the workers in the Aari, embroidery sector are being paid less than the minimum wages determined by the state government of Maharashtra in 20196. The financial mobility is somehow stagnant and it is creating multiple futuristic risks with the increase in the inflation rate.

Since there was no evidence of intergenerational transfer of occupation, one can easily determine a mix of financial conditions, religious identity and regional disparity as the sole force working behind the phenomenon of migration. Out of it, the regional disparity has emerged as the major driving force in the migration where the search for better livelihood is the ultimate goal. In fact, the Uttar Dinajpur district is the least developed district of West Bengal (Jansankhya Sthirata Kosh, 2006) while Seemanchal region which mainly consists of Araria, Kishanganj, Purnia and Katihar district is very bad in shape in HDI rankings (Singh & Keshari, 2016). A larger concentration of Muslims within these regions can also be a determinant of backwardness because of the state’s ideological biases towards the policy implementation, development initiatives and resource distribution.

2.Migration and Trickle-down Effect

Migration in Indian context and specially for low income groups is seen as steps for financial improvement or reduction in poverty through trickle-down effect. With the discussions and observations in the field, it was found out that the migrant workers were moved to Mumbai for more money accumulation and an intention of sending remittances in good chunks was also attached to it.

Degree of Changes visible in the family conditions? |

|||||

What is the amount of Remittance (If sent regularly) |

A Little Bit Improvement |

Fair Improvement |

No Improvement |

Conditions got bad/Worsen from Past |

Total |

0-2,000 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

6 |

2,000-4,000 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

4,000-6,000 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

6,000-8,000 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

8,000 and Above |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

Nil |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

Total |

14 |

8 |

5 |

3 |

30 |

Table 4.20. What is the amount of Remittance (If sent regularly) *Degree of Changes visible in the family conditions

Around 60 percent of the respondents stated that they sent remittances less than the amount of four thousand. Taking note on the inflation and minimum living cost, it is very difficult for their families to bear basic expenses in a fluid manner. It can be easily concluded that the amount of remittance sent to the families is directly proportional to the changes experienced by the worker as the development felt in post-migration period. The increasing economic disparity is the general trend of neoliberal economy and the sections of society at the margins feel its heaviest impact. Similarly, looking at the amount of remittances and the changes felt by the workers, it is determined that the agriculture is saving them from being more deprived.

Accessibility to fundamental resources and approach towards acquiring more goods for human development create an environment where the decision for migration becomes important. The migrating men in the Aari embroidery are also affected by such things since a majority of them were generating basic resources through agriculture. While evaluating the benefit of migration one has to check the degree of changes that one has experienced. These changes were attributed on the basis of accessibility of resources including those of luxurious goods crucial for human development. Twenty-two respondents out of thirty agreed that their familial conditions have improved due to their migration. It is quite clear that the trickling down of financial conditions have been achieved by the migrant workers by working in more inustrialised regions. Although there were several cases where more than one member of the family has migrated and the degree of improvement might be an outcome of the joint efforts. A total of eight respondents felt that the degree of improvements they have seen in their lives is fair in relation to the pre-migration period. Contrary to this one-sixth of the respondents didn’t felt any improvements in their lives while three respondents felt a negative trend in their comparative development.

The Neoclassical model which was adopted for providing a theoretical sense to the process of migration is quite visible through this data. In the given context, poverty combined with the lack of livelihood opportunities is making a backdrop of migration while individual agency on decision making, choice-based migration, employment probability and wage increment are providing elemental features in formulating the overarching framework of analysis. Although having a caste-based network is somehow providing the migrant workers to move into multiple cities in a concurrent manner. And this factor is a major agent of concurrently migrating within the Aari embroidery sector of around forty percent of the respondents.

3.Demonetisation, GST and its impact of Micro Enterprises

8 November 2016 was one of the shocking dates for the unorganised sector running on cash transfers in which the micro- enterprises were affected the most. The situation which was got created in the Aari embroidery sector is illustrated by a worker as follows:

“Notebandi ke time pura maal saste me bechna pada aur dusron se udhar lekar kaam chalana pad rha tha. Do mahine tak sahi se mazdoori nhi mili aur ek mahine to samjho ek bhi dhang ka order nahi aaya. bahut log isi dauran ghar chale gaye. Baad me kuch log wapas aaye par kuch nahi bhi aaye”.

(During Demonetisation we were compelled to sell the finished work in lower rates and also we lend some money for running the workshop. For two-three months the wages were not provided properly and around two-three months there was not a substantial order. Many of the workers left to their home and some of them returned while some didn’t return).

The shock produced by the demonetisation not only produced a wage less period but also sent back some of the workers in a permanent sense which can be considered as a loss of livelihood. Though the pace of work gets normalised within the next four-five months the strength or amount of work was not the same as before. Although there have been empirical studies which have shown that shock therapy such as demonetisation didn’t push the unregistered enterprises into the bank based transactions and the value chain attached to it. In the opposite sense, it has produced long-lasting negative impacts on these enterprises (Kurosaki, 2019).

Goods and Services Tax has been implemented to bring upon the uniformity in the tax collection. But for the micro enterprises, it brought negativity in terms of demand and supply. In fact, when the researcher went to the field owners of the workshops usually asked the question of whether I was from the income tax department or BMC. It was the fear that was coming out due to the taxation regime and its impact on the textile regime. The Aari embroidery comes under the 18% slab and it has negatively impacted the wages received by the workers. The wage is completely dependent upon the demand and supply dynamics and GST has somehow curtailed the amount of demand from above of the chain. The whole chain operates in an informal manner and data is not being maintained properly which produces insecurity. In the name of the tax, every part of the chain has lowered the wages given to different contributors. But contrary to demonetisation GST was seen as a more effective policy in promoting bank-based transactions (ibid).

Citing the cases of GST and Demonetisation one worker tagged the policies for being biased and improper. He said:

“Notebandi se Musalmanon ka jyada nuksan hua hai kyun ki musalman vyapar me bank se len den nhi karta… aksarke cash se hi kaam chalta hai. GST se bhi bahut nuksan hua hai hamen kyunki upar se order aana band gya, seth log dar dar ke order dete hain aur pakki rasid par bhi kaam bilkul band kar diye hain”.

(Muslims are heavily impacted by the Demonetisation because Muslims do not prefer the transaction through banking and in most of the cases they prefer things to be done through cash. GST has also damaged our business orders from above the chain get stopped and the middlemen stopped giving orders. They give orders with fear and they have stopped us giving a proper bill.)

The cause and effect of the greater economic reforms of contemporary times have produced a negative impact on the Aari embroidery sector. Reminiscences of those ‘reforms’ can easily be traced and felt while evaluating the livelihood situatedness of migrant workers engaged in Aari embroidery sector.

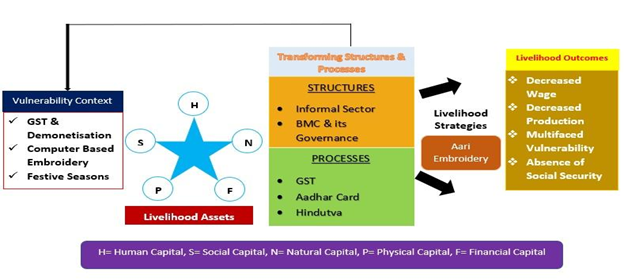

4. Livelihood Analysis through Sustainable Livelihood Framework (SLF)

Department of International Development (DFID) has scientifically developed a Sustainable Livelihood Framework (SLF) (DFID, 2008) for analysis of the elements involved in a particular livelihood and capturing the dynamics emerging out of certain practices and conditionality. In a similar fashion, the author has tried to contextualise the framework to analyse the livelihood of migrant Aari embroidery workers. The contextualisation has been done in order to review the multiple factors, resources, processes and outcomes coming out of various strategies adopted by the target population.

The livelihood analysis through SLF is comprised of four major components- Vulnerability Context, Livelihood Assets, Policies, Institutions and Processes, Livelihood Strategies and Outcomes.

● Vulnerability Context: There are three main components under this. The first components try to highlight the problems created due to GST and Demonetisation which mainly revolves around the sudden breakdown of value chain and demand and supply equilibrium. The second component is related to the introduction of Computer-based embroidery in the textile industry which is impacting the wages of the workers in a negative sense. Since the textile market is more depended upon the cost of production, therefore, the mechanised embroideries are low in cost and day by day it is hijacking the market created by Aari embroidery. In addition to it, mechanisation is inversely impacting the wages of workers. This was explained when a worker said:

“Jis tarah se baaki labour wale kaam ke daam badhe hain us speed se Aari ki mazdoori nahi badh rahi”.

(The manner in which the other labour rates are increasing, it is not same with the Aari work)

The impact of this can be seen in the decreased number of workers in the majority of workshops that was visited by the researcher. In other terms, the trend is producing negative trends among the migrants and also among the aspiring ones. Apart from it, it is pushing people to opt out an alternative source of income or to involve more persons from the house in the same profession in order to maximise the income. The last component is related to festive seasons which is trying to show how seasonality impacts the total demand and supply. In fact, it is the festive seasons where the workers earn the most because the wages are decided on the basis of number and types of designs along with its numbers.

● Livelihood Assets: It mainly includes five major capitals involves in sustaining a livelihood i.e. Human capital, Social capital, Natural capital, Physical capital, and Financial capital. These capitals in the context of Aari embroidery are necessary to maintain the sustainability of the livelihood. In the contextual sense, Human capital simply means the potential that a person one has which can be characterised as the expertise in making multiple designs of Aari embroidery. The social capital of a worker completely depends upon the networks that the owner of the workshop have built through multiple sources so that one can fetch orders as many as one could. The natural capital involved in Aari embroidery is disguised in nature within the workers and their potentials. Physical capital mainly involves the infrastructural components like areas of workplace and quality of its building, number of machines and its quality parameters along with the physical fitness of a person to be involved in the Aari embroidery work for a longer period of time. Financial capital is dependent upon the wages and savings created through it which can be used as the capital for creating other opportunities or self-employment.

● Policies, Institutions and Processes: GST and demonetisation have been two main policies which have been heavily discussed by the respondents. Its impact on the value chain and limiting the orders for a certain period of time was devastating for the workers. Apart from it, an institution like BMC was also critically seen upon and a negative connotation was received from the field. Taxation changes have seriously hit the workers and it has diminished the scope for further development in most of the workshops.

● Livelihood Strategies and Outcomes: Livelihood strategies are comprised of the various methods used for sustaining the livelihood. But in the case of Aari embroidery work, only innovation can help along with creativity in creating designs of embroidery. In most cases, designs are pre-decided and the workers serve as a means of producing embroidery work. As an outcome, the perpetual alienation comes along with the maintenance of precarity in terms of life and livelihood.

Globalisation has impacted particularly those population who don’t have accessibility to improved/ enhanced technology. Being a skill-based job done by semi-technical sewing machines, the workers of the Aari embroidery have started facing an existential question from the computerised machinery. The unsustainability has become a common phenomenon to the livelihood of the Aari Embroidery workers. The external factors derived upon market closely linked to the unsustainability. The phenomenon of sweatshops is becoming a reality of this sector where the workers and their workshops are becoming a part of a chain of a larger and virtual production ‘unit’.

5. Emergence of Precariousness

Precarity is generally defined on three lines which are based on three different aspects of vulnerability i.e. Existential, financial and social insecurity. In the creation of these insecurities, state role is central not only in making economic policies but also imposing certain aspects of ideological rationality. In the last 30 years, certain economic policies directed towards the neoliberalism has impacted society by increasing inequality in manifold terms. The precariats are not only facing challenges in economic terms but their rights are also getting faded due to persistent insecurity. For migrants, it is the question related to survival which deeply affects their lives and produces vulnerability in multiple forms (Standing, 2011).

In case of Aari Embroidery workers, precariousness is emerging due to the changing market relationship which has been influenced by economic policies, Hindutva ideological spirit as the underlying ideology of the state, and also the cost of surviving in Mumbai. The economic policies like demonetisation and GST have produced a deep wound in the working style and amount of production. These legislations have heavily impacted the value chain system which was existing before and it was the workers who lose the most. The amount of labour applied versus the number of wages has fallen down sharply comparative to other skill-based jobs. The Hindutva ideological spirit is impacting them in an indirect sense where the maximisation of business is getting limited to a particular sphere. In fact, Mumbai has its own history and struggle of space in the business of any kind where Muslims are largely have been compartmentalised to specific works waste/plastic recycling, meat sale and purchase and embroidery are the best examples of it. The phenomenon of late capitalism has increased the gaps which were existing prior to it. In the same manner, the flow of migration is also increasing day by day. With the compartmentalisation process of Muslim workforce in Mumbai the load on the particular sector is leading to economic exploitation and with other factors, it is leading to a continuous process of precariousness among the Aari embroidery workers.

6. Evaluating Citizenship Rights

Migration and citizenship rights are the non-related terms as per the constitutional guarantees. But in reality, it is somehow opposite facts like only 2 persons out of 30 use government aided medical services shows the failure of the state in providing services to its citizens. Food security is the other issue which comes under economic rights and once again it becomes a hyper-reality of covering each citizen under Right to food security when only two out of thirty respondents claimed that they have ration card under Mumbai’s address. Coming under the facility of the act not only creates a nutritional deficit but also decreases the overall savings of an individual. None of the workers is aware of any schemes centred for migrant workers and the fact that five out of thirty respondents don’t have their Aadhar card is a matter of concern in the digitized era. When it comes to political rights voting rights becomes crucial and the fact that only 5 respondents have the voting rights under Mumbai’s address is somehow depriving the community politically. This creates a problem and diminished the bargaining power of embroidery workers in terms of policy making as well as decision making within the government bodies.

Conclusion

The present study was able to draw upon the process of migration. As explained by the Neoclassical theory (Todaro, 1969), the data also reflected the role of individual rationale and cost benefit calculations forming the background of migration. Since the majority of the workers belong to a particular region and a specific caste too, thus the role of social capital and networking based upon that capital can’t be denied. Based on those relationships, each worker is able to think about the decision to moving rather than forcefully being pushed into the market. The livelihood induced migration is the main pattern where the adults wish to earn money for their families. The rural distress and small landholding by the majority of the respondents makes a low profit-making trend within their rural and agriculture-based economy. Though the Aari embroidery sector in the context of Mumbai comes under the highly unorganised sector and there are a lot of risks involved in it. The value chain that the workshops are connected builds the foundation of production and with the increase in workshops along with mechanisation of the embroidery sector, a negative trend is emerging out of the sector. In a nutshell, Aari embroidery work might have emerged as a source of livelihood for all of the workers but the risks attached to it are alarming. The requirement of physically active bodies make the livelihood very age-specific and this is also supported by the data where a majority of the workers are less than the age of 32. The demographic dividend might be the supporting factor in it thus one can easily say that the Aari embroidery as a sector employs a majority of the youths in it. In addition to it, the zero participation women in this sector make it as a gendered space in the context of the location from where the data has been collected.

The wages earned by the workers depend upon the tasks performed by them rather than a fixed wage per month. In this way, seasonality attached to it produces uneven demand and supply which produces an increase or decrease in wages. Having skills of only Aari restricts the workers for changing source of livelihood in an urban context of Mumbai. The remittances sent to their home place is quite less as compared to the rising inflation though there are some fluctuations in the festive seasons by and large the vulnerability is getting removed in a very low speed. Though more than 50 percent of the respondents affirm that there is a degree of improvement after migration. Thus, it can be said that the migration and engagement in Aari embroidery as a livelihood is somehow benefitting the worker and his family. While evaluating the livelihood it was also analysed how the policy, process and institutions interconnectedly influencing the livelihood of the worker in relation to their identity and place of stay in area of study.

Citizenship rights are fundamental to evaluate the socio-economic along with political situatedness of a person. If someone’s place of stay, domicile location or identity is producing hindrances in accessing the schemes centred for the welfare of the same population then it is the failure of state and its mechanism to reach out such a population. In this way, the ‘Aadhaar Regime’ has failed a section of the population to access the basic social security nets despite being a citizen of the country. The politics of Mumbai have a greater impact in a structural manner and the politics of ‘Son of Soil’ has produced perpetual marginality among the Muslims of Mumbai and the biased behaviour from various institutions is also problematic in its essence. Therefore, a right based approach should be incorporated while making legislation affecting the population either in direct or indirect manner.

Possible way Forward

This section is centered around the suggestions that the author has constructed through available literature, data analysis and major finding. Apart from it, the informal discussions with the workers and owners of the workshops. The suggestions are subdivided into two parts i.e. Policy Planning and further research.

1. Policy Planning

● There is an urgent need to recognise the fact that a majority of migrants in Mumbai lives in slum quarters and the paperwork by them is quite porous. Therefore, the individual’s identity card should be considered as the sole requirement for accessing social security nets. Though there should be a mechanism for screening out non-eligible persons and an individual should be considered an agency to make decisions for themselves.

● There are policies for lending loans for micro-enterprises in urban areas but due to paperwork and a construct of governmental threat is required to be challenged. Non-governmental agencies could be hired in order to enhance the accessibility of their needs.

2. Further Research

The suggestion of further research is based upon three foundations which include the available literature, data analysis and major finding of it along with the limitations that the study consists.

● There is a need to do research on the nature of labour required for embroidery work and its impact on the creation of Gendered Spaces.

● The phenomenon of sweatshop and Marginalised communities should be studied in the context of Urban as well as rural Sociology.

● Precariousness is one of the strongest emerging reality, especially among the low paid working class. Thus, livelihood centric social should consider this fact with developing a contextual framework to understand the dynamics of precarity in the Indian economy and working masses.

● For challenging precarity Basic Minimum income is often produced as a solution for though it is a matter of deep concern how basic minimum income challenge the structural causes (like caste) which influence livelihood induced migration

Note

1. The data of this article has been collected during July 2018 to September 2018 as part of MA dissertation.

References

-

Abbas, R. (2016). Internal migration and citizenship in India. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies,42(01), 150-168.

-

Abbas, R., & Varma, D. (2014). Internal Labor Migration in India Raises Integration Challenges for Migrants (Rep.). Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved February 12, 2018, from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/internal-labor-migration-india-raises-integration-challenges-migrants

-

Anwar, A. (2001). Masawat ki Jung Pasemanjar: Bihar ke Pasmanda Musalman. New Delhi: Vani Prakashan.

-

Bhushan, J. B. (1990). Indian Embroidery. New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of India.

-

Bhattacharya, P. (1998). The Informal Sector and Rural-Urban Migration: Some Indian Evidence, Economic and Political Weekly, 33(21), 1255-1262.

-

Bino Paul G D, Susanta Datta, Venkatesha Murthy R (2011) Working and Living Conditions of Mumbai Women Domestic Workers: Evidence from Mumbai, Adecco TISS Labour Market Research Initiatives (ATLMRI), Discussion Paper Retrieved February 12, 2018 from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Venkatesh_Murthy7/publication/254412575_Working_and_Living_Conditions_of_Women_Domestic_Workers_Evidences_from_Mumbai/links/560bcba008ae6de32e9a9f64/Working-and-Living-Conditions-of-Women-Domestic-Workers-Evidences-from-Mumbai.pdf.

-

Breman, J. (1996). Footloose labour: working in India’s informal economy. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press.

-

Borhade, A. (2016). Internal Labour Migration in India: Emerging Needs of Comprehensive National Migration Policy. In Internal migration in contemporary India. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd.

-

Buchanan, F., & Jackson, V. H. (1986). An account of the district of Purnea in 1809-10. New Delhi: Usha.

-

Contractor, Q. (2012). ‘Unwanted in my city’—The making of a ‘Muslim slum’ in Mumbai. In Muslims in Indian Cities: Trajectories of Marginalisation (pp. 23-42). London: C Hurst & Co.

-

Das, K. C., and S. Saha (2013). ‘Inter-State Migration and Regional Disparities in India’. Retrieved February 11, 2018, from https://www.iussp.org/sites/default/files/event_call_for_papers/Inter-state%20migration_IUSSP13.pdf

-

DFID’s Sustainable Livelihoods Approach and its Framework [online file]. (2008). Retrieved February 9, 2019, from http://www.glopp.ch/B7/en/multimedia/B7_1_pdf2.pdf

-

Haan, A. D. (2011). Inclusive growth? Labour migration and poverty in India. Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 54(03), 03-28.

-

Haas, H. D. (2010). Migration and Development: A Theoretical Perspective. International Migration Review,44(1), 227-264.

-

Harris, J. R., & Todaro, M. P. (1970). Migration, Unemployment and Development: A Two-Sector Analysis. The American Economic Review,60(1), 126-142.

-

Jansankhya Sthirata Kosh (National Population Stabilisation Fund). (2006). Rank of Districts in West Bengal according to Composite Index. Retrieved February 14, 2019, from http://www.jsk.gov.in/wb/wb_composite.pdf

-

Jha, V. (2008). Trickle Down Effects of Inter state Migration in a Period of High Growth in the Indian Economy (Working Paper) (pp. 1-34). Coventry: University of Warwick. Centre for the Study of Globalisation and Regionalisation. Retrieved March 3, 2019, from https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/pais/research/researchcentres/csgr/papers/workingpapers/2008/25308.pdf

-

Kundu, A., & Sarangi, N. (2007). Migration, Employment Status and Poverty- An Analysis across Urban Centres, Economic and Political Weekly, 42(04), 299-306.

-

Kurosaki, T. (2019). Informality, Micro and Small Enterprises, and the 2016 Demonetisation Policy in India. Asian Economic Policy Review, 14(1), 97-118.

-

Mhaskar, S. (2013). Indian Muslims in a Global City: Socio-Political Effects on Economic Preferences in Contemporary Mumbai (working paper). Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity.

-

Mishra, D. K. (2016). Internal migration in contemporary India. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd.

-

Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai. (2005). Mumbai city Development plan: 2005-2025, Mumbai.

-

Naoroji, D. (1901). Poverty and un-British rule in India. London.

-

OECD and UNIDO. (2004). Effective Policies for Small Business: A Guide for the Policy Review Process and Strategic Plans for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise Retrieved 8 February 2019 from https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/2009-04/Effective_policies_for_small_business_0.pdf

-

Pattanaik, B., (2009), Young Migrant Construction Workers in the Unorganized Urban Sector, South Asia Research, Sage Publication, 29(1), 19–40.

-

Planning Commission. (2008). Eleventh Five Year Plan, Vol III: Agriculture, rural development, industry, services and physical infrastructure (pp. 394–422). New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

-

Shaban, A. (2008). Ghettoisation, Crime and Punishment in Mumbai. Economic and Political Weekly,43(33), 68-73.

-

Sinha, B. P. (1926). THE BEAUTIES OF INDIAN EMBROIDERIES. The American Magazine of Art,17(11), 586-587.

-

Singh, P., & Keshari, S. (2016). Development of Human Development Index at District Level for EAG States. Statistics and Applications, 14 (1 & 2), 43-61. Retrieved February 14, 2019, from http://ssca.org.in/media/4_2016_HDI_t1hcMZm.pdf

-

Srivastava, R.S. (2011). Labour migration in India: Recent trends, patterns and policy issues’. Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 54(33), 411–440.

-

Standing, G. (2011). The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. London: Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing.

-

Taylor, E. J. (1999). The New Economics of Labour Migration and the Role of Remittances in the Migration Process. International Migration,37(1), 63-88.

-

Thorner, D. (1956). The Agrarian Prospect in India. New Delhi: University Press.

-

Todaro, M. P. (1969) A Model for Labor Migration and Urban Unemployment in Less Developed Countries. The American Economic Review, 59(01), 138-148.

- Wilkinson-Weber, C. M. (1997). Skill, Dependency, and Differentiation: Artisans and Agents in the Lucknow Embroidery Industry. Ethnology,36(1), 49-65.

End Notes

1. MA Social Work in Dalit and Tribal Studies and Action, School of Social Work, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Deonar, Mumbai 400088, India.E-mail: imraniramtwit@gmail.com

2. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. (n.d.). Migration. Retrieved September 4, 2018, from http://censusindia.gov.in/Census_And_You/migrations.aspx

3. Ahmad, S. (2018, July 19`). Drawn By Development, North Indians Continue To Migrate To South. Outlook. Retrieved February 28, 2019, from https://www.outlookindia.com/magazine/story/drawn-by-development-north-indians-continue-to-migrate-to-south/300407

4. Rajadhyaksha, M. (2012, September 17). 70% migrants to Mumbai are from Maharashtra. The Times of India. Retrieved October 22, 2018, from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/70-migrants-to-Mumbai-are-from-Maharashtra/articleshow/16428301.cms

5. Mumbai (Greater Mumbai) City Census 2011 data. (n.d.). Retrieved October 14, 2018, from https://www.census2011.co.in/census/city/365-mumbai.html

6. Department of Labour. (2019). Maharashtra: Minimum Wage w.e.f. 1st January, 2019 to 30th June, 2019(Government of Maharashtra). Retrieved February 13, 2019, from https://www.sarkarjobinfo.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Maharastra-Minimum-Wages-01.01.2019-to-30.06.2019.pdf

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)